Where hyenas are used to treat mental illness

- Published

Somalia has one of the highest rates of mental illness in the world and with a healthcare system devastated by years of war, most sufferers receive no medical help. Many are chained up - to trees or at home. Some are even locked in cages with hyenas. But one man is trying to change all that.

Dr Hab's advert runs up to three times a day on Mogadishu's radio stations.

"He's gone crazy! He's running away!" screams the actor. "Chain him down!"

The scenario is familiar in Somalia. A man has become possessed by spirits and the only option for his family is to restrain him and call the sheikh. But as the young man protests, a voice that challenges Somali tradition booms out.

"Stop with the chains!" the voiceover orders. "Take him to Dr Hab's hospital! If he's having mental problems, take him to Dr Hab. He won't chain him, he'll help him."

Dr Hab is not actually a real psychiatrist. Rather it's the persona of Abdirahman Ali Awale, a nurse who after three months of specialist training from the World Health Organization (WHO), has made it his mission to rescue Somalia's mentally ill. He claims he is able to treat everything from post-natal depression to schizophrenia.

But the alternative to a trip to Hab could be a visit to one of Somalia's popular herbalists or sheikhs who still advocate traditional - and sometimes barbaric - cures.

"There is a belief in my country that hyenas can see everything including the evil spirits people think cause mental illness," says Hab. "So in Mogadishu, you will find hyenas that have been brought from the bush and families will pay £350 ($560) to have their loved one locked in the room overnight with the animal."

The expensive treatment - more than the average annual wage - is as brutal as it sounds. By clawing and biting at the patient, the hyena is thought to force the evil spirit out. Patients, including young children, have been known to die during the process.

"We are trying to show people that this is nonsense," says Hab. "People listen to our radio advert and they learn that mental illness is just like any other and needs to be treated with scientific methods."

Hab's campaign was prompted by an incident in 2005 when he witnessed a group of female patients being chased through the streets by youths. "There was no-one to help them," he says. "I decided after that I would have to open Somalia's first mental hospital."

The Habeb Public Mental Health Hospital in Mogadishu became the first of Hab's six centres across Somalia. Together, they have now treated over 15,000 patients.

There were only three practising psychiatrists in the whole of Somalia at the last count, and Hab - despite his lack of advanced qualifications - is head of what has become the country's leading provider of mental health services. He even carries a letter from the minister of health that says so.

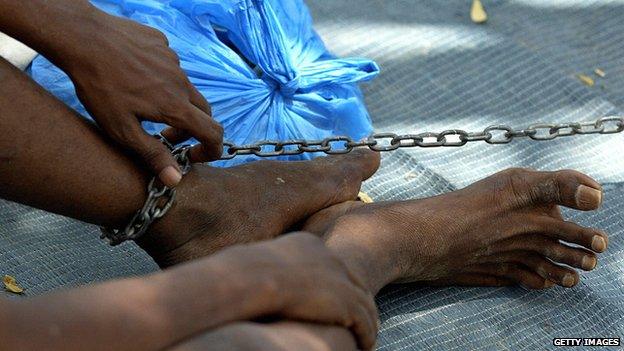

Chaining mentally ill patients to trees has been a widespread practice in Somalia

Hab faces a near insurmountable task. WHO estimates that one in three Somalis either is or has been affected by mental illness, compared to a global average of one in 10. In parts of the country, where the population has been the most psychologically scarred from decades of conflict, the rate is even higher. Cases of post-traumatic stress disorder are common and the situation is further complicated by widespread substance abuse.

"Khat is a big, big problem," says Hab of the herbal stimulant which has been chewed for centuries in East Africa. Side effects are thought to include anxiety and even psychosis. "We treat them in the hospital and they leave, but then they start eating khat again. Sometimes I see the same patients seven or eight times."

Western aid agencies in Somalia have often promoted projects targeting communicable diseases, not least because results are quicker and cheaper to obtain. Hab, meanwhile, says he is left to run his organisation with minimal resources and an erratic supply of psychotropic medicines that he sources from NGOs and private pharmacies.

Even getting sufferers to recognise that their condition constitutes an illness is difficult. Psychological problems are more likely to be reported by Somalis as physical pain - headaches, sweating, and chest pain. Some concepts of mental illness do not even exist in Somali culture - depression, for example, translates as "the feelings a camel has when its friend dies".

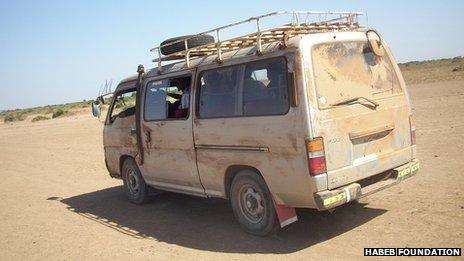

Dr Hab uses his minibus to rescue patients who have been left in chains

But nothing is more indicative of the population's poor understanding of mental health than the widespread practice of chaining-up sufferers to trees and in rooms. GRT, an Italian NGO, has documented sufferers who have been chained up their entire life.

"I myself have saved many patients who have been left to die," says Hab who drives a minibus into rural areas, unchaining people and taking them to one of his centres. "Parents, siblings, relatives - they've just been chained up to a tree and the family has gone."

The WHO has funded a "Chain Free Initiative", with the aim of eradicating the practice altogether, starting with the use of chains in hospitals. But even Hab admits to having chained up some of his most aggressive patients.

He tells the story of how, in 2007, one unintended consequence of his acquisition of a batch of the anti-psychotic drug, fluphenazine hydrochloride, was an increased appetite in his patients. They took to scaling the walls of his hospital in Mogadishu to scavenge for food. But still desperately unwell, some of the escapees had been shot when they ignored orders at a military checkpoint. Chaining them to their beds, concluded Hab, was the only option.

Dr Hab regularly speaks in public to raise awareness of mental health issues

"Many patients take a long time to treat," he says. "There has been no outside help focussed on treating mental health problems and the main reason NGOs are not getting involved is because of the expense."

Hab is motivated by the thousands of patients he believes remain chained up in private homes. He sends through a spreadsheet showing what he needs - new mattresses, food for patients, and diesel for his minibus. There is also a shortage of qualified psychiatrists and nurses. The daily struggle to provide for his patients and the suffering he witnesses is clearly taking its toll.

"Physiologically and mentally it's a very hard job" he says. "I was healthy when I started, now I suffer from diabetes. I am dealing with big, big problems all by myself.

"I have cried on TV, I have cried in public places, I have cried in front of presidents," he says. "Even now I feel like crying."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external