The problem with taking too many vitamins

- Published

Millions of people swear by vitamin supplements. But many are wasting their time and some could even be harming themselves, argues Dr Chris van Tulleken.

In November 1912 a party of three men and 16 dogs set out from a remote base in eastern Antarctica to explore a series of crevasses many hundreds of miles away.

Three months later just one of the men returned. His name was Douglas Mawson. His skin was peeling off and his hair was falling out. He had lost almost half his body weight. He recounted what Sir Edmund Hillary described as "the greatest story of lone survival in the history of polar exploration".

A month into their journey, one of the team, along with the tent, most of the provisions and six dogs plunged into a crevasse, never to be seen again. Mawson and the other surviving member, Xavier Mertz, started to return to base, surviving in part by eating the remaining dogs. After a few weeks Mertz developed stomach pains and diarrhoea. Then his skin started to peel off and his hair fell out. He died incontinent and delirious a few days later.

Mawson suffered similar symptoms. With the kind of understatement typical of his generation of polar explorers he described the skin of the soles of his feet peeling off: "The sight of my feet gave me quite a shock, for the thickened skin of the soles had separated in each case as a complete layer... The new skin underneath was very much abraded and raw."

It was the suffering of early explorers and sailors that motivated the first studies of vitamins and their deficiency diseases.

At first sight Mawson's story seems to be another such tale - starvation combined with a lack of some vital nutrient. In fact, Mawson's description of his symptoms is an almost textbook description of vitamin A overdose - probably from eating dog liver. As little as 100g of husky liver could give a hungry explorer a fatal dose.

Mawson lived to the decent age of 76 but in his story we find the cautionary tale for our times - vitamins can be very bad for you.

This piece is about what we have learned about vitamin supplements in the last few years - if you are healthy, and you live in a country like the UK, taking multi-vitamins and high-dose antioxidants may shorten your life.

For most of us, for most of the time, they're unhealthy. "Argh!" I hear you say, "I spend loads of money on them and the claims on the packet are really persuasive. Everything, from my full head of hair to my sex life, depends on them!"

I want to get into this in a bit more detail because the vitamin companies certainly don't agree with me. So why do we believe they're useful and why do we take them?

Vitamins are essential for life, and there are groups of people even in the UK who benefit from specific supplementation, but general unsupervised vitamin pill-popping is more than just a waste of money. The problem is that we all feel very warm and fuzzy about vitamins because, firstly, the tales of deficiency are so horrific, secondly, we read breakfast cereal packs and thirdly, a double-Nobel laureate called Linus Pauling liked vitamin C in vast, vast doses.

All this is packaged by the people now selling us vitamins over the counter into that most beguiling of all logical falsehoods - if a little is good, then more must be better.

Now I knew the names of the most obscure vitamins long before medical school because I have always had a fondness for the kind of multicoloured, artificially flavoured breakfast cereals that are marketed using a combination of unlikely cartoon animals and claims of being "vitamin and mineral-enriched".

And it has to be said that this vitamin and mineral enrichment of staple food has been one of the most effective public health interventions in history. It continues to save countless lives per year even in Europe.

So, while you shouldn't eat dog liver in Antarctica, vitamin A deficiency hugely increases the risk of blindness and death in children with measles and diarrhoea in developing countries. So the World Health Organization recommends a very strict amount and cautions that higher doses can cause birth defects in early pregnancy among other problems.

Refugee child in Chad receives vitamin A supplement

So vitamins do make a huge difference to life expectancy in some circumstances, which is persuasive, and the breakfast propaganda catches us in our most vulnerable, bleary-eyed, early morning state, hinting to us that these vitamins have some sort of catch-all, beneficial effect on our lives, that will transform us into the healthy, energetic beautiful people/cartoon creatures portrayed on the cereal box.

These things contribute to a general ideal of healthfulness of vitamins. And then there's Linus Pauling.

Whether or not you've heard of him, Linus Pauling is a major influence on vitamin and nutrient culture. It's almost impossible to imagine someone with more authority and credibility. He won two Nobel prizes and was, by all accounts, a genuinely good bloke. He wrote a book in 1970 saying that high doses of vitamin C could be effective in combating flu, cancer, cardiovascular disease, infections and degenerative problems.

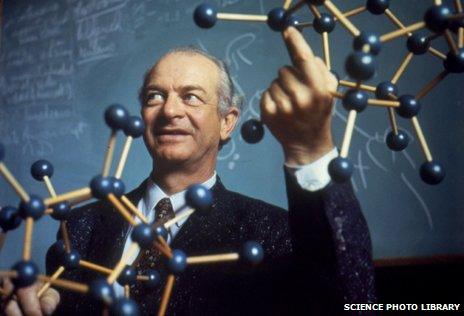

Nobel laureate Linus Pauling took immense quantities of vitamin C

He took immense quantities himself, hundreds of times the required amount, and lived to a ripe old age surrounded by many great grandchildren. He was the poster boy for mega-dosing of vitamins and this contributed to the growth of an industry supported by the belief that supplementation of these molecules in our diet is beneficial in almost every way imaginable.

But rather than taking one man's word for it, however credible, it's worth looking at the results of studies that look at what happens to people who take these supplements for long periods of time.

Looking at any one individual study won't be very revealing to answer the question of whether vitamin supplementation is good for you. They're densely scientific and the conflicts of interest can be very hard to spot.

For the answer you have to turn to what are called "systematic review papers". This is where independent scientists gather up all the available data and re-analyse it to answer big questions.

Here's what a couple of them say:

"We found no evidence to support antioxidant supplements for primary or secondary prevention [of diseases of any kind]. Beta-carotene and vitamin E seem to increase mortality, and so may higher doses of vitamin A. Antioxidant supplements need to be considered as medicinal products and should undergo sufficient evaluation before marketing". (See references below).

Just to be clear - "increase mortality" - that means they're killing you. These are powerfully bioactive compounds but they're not regulated in the same way as drugs. Whatever you think about the regulation there should surely be a warning on the pack if there's data saying they're bad for us.

The next question is - why are they bad for us? It's very hard to pick apart the data, partly because vitamins are a fabulously diverse group of chemicals.

I'm going to include what people normally refer to as minerals under the heading of vitamins. They're required in the diet not for energy, but as chemical partners for the enzymes involved in the body's metabolism - cell production, tissue repair, and other vital processes.

Their functions are understood largely by their deficiency diseases so we're not exactly sure of precisely what they all do or how they interact. Antioxidants provide a nice example. They soak up the very toxic, chemically-reactive by-products of metabolism called free radicals. These free radicals, left unchecked, can cause damage to DNA and may be linked to cancer.

Your cells are full of antioxidants but surely taking more would be better? Right? Keep those cancer causing radicals under control? Well, unfortunately, your body's immune system fights infections by using free radicals to kill bugs. Exactly what effect huge quantities of extra antioxidants could have on this is not clear but it's easy to imagine that it might not be good and you could get more infections.

Vitamin A is linked to increasing lung cancer in smokers. Excess zinc is linked to reduced immune function. Long-term excessive intake of manganese is linked to muscle and nerve disorders in older people. Niacin in excess has been linked to cell damage. And so on.

Vitamin A is linked to increasing lung cancer in smokers

And it gets more complicated still when you start mixing everything up in one tablet. For example, different minerals compete for absorption. If you take large quantities of calcium you won't be able to absorb your iron. If you take large quantities of iron you won't be able to absorb zinc. If you take vitamin C you'll reduce your copper level.

So it's not just that taking lots of one thing is not good for you, it's that it may cause a dangerous reduction in something else even if you are also supplementing that. To work out the optimal ratios is all but impossible although some manufactures claim to have worked it out.

So when are supplements recommended? The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends certain supplements for some groups of people who are at risk of deficiency, including:

Folic acid for all women thinking of having a baby and pregnant women up to week 12 of the pregnancy.

Vitamin D for all pregnant and breastfeeding women, children aged six months to five years, people aged 65 and over and for people who are not exposed to much sun, for example people who cover up their skin for cultural reasons, or people who are housebound for long periods of time.

Finally a supplement containing vitamins A, C and D is recommended for all children aged six months to four years. This is a precaution because growing children may not get enough, especially those not eating a varied diet, such as fussy eaters.

Your GP may also recommend supplements if you need them for a medical condition, external. If you decide to take supplements, stick to within the RDA, unless you've had guidance from a state-registered dietician or clinical nutritionist to exceed the dose. If you've got questions about dosage levels, consult a state-registered dietician or clinical nutritionist.

The tales of deficiency combined with the success of enrichment programmes mean that it's easy to make that leap of logic that if a little is good then more must be better.

And if you read my article last week on water you'll see where this is going. I could do this every week. The same article. Substitute water for vitamins/probiotics/antibiotics. Don't trust the science done by the people who are trying to sell them to you and don't assume that if some is good more must be better.

It's like beer. Or coffee. Or computer games. Goldilocks was right about things needing to be just right.

References:

Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Simonetti RG, Gluud C. Antioxidant supplements for preventing gastro-intestinal cancers, , 2004

Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud C, Antioxidant supplements to prevent mortality, The Journal of the American Medical Association, 2013

Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C, Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2012

Chris van Tulleken is on Twitter: @doctorChrisVT

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

Trust Me I'm a Doctor is broadcast on 17 October on BBC Two at 20:00 BST, or catch up with iPlayer