10 ways christening has changed

- Published

Prince George's christening on Wednesday comes 31 years after his father Prince William in 1982. Here are 10 ways in which baptisms have changed since then.

1. There are fewer christenings

George's christening is the exception rather than the rule. And not just because he's a royal.

Although christenings were already in decline, one in three infants was still baptised into the Church of England in 1980. By 2011 that had fallen to just over one in 10. The overall number of baptisms - of people of all ages - witnessed a similar decline, from 266,000 in 1980 to 140,000 in 2011.

It's a similar story in the Catholic Church, although the major drop-off in baptisms happened between 1964 and 1977, when the number halved. There's been a far gentler downward trend over the past three decades, recently stabilising at about 60,000 baptisms a year.

2. But more godparents

Liz Hurley chose Sir Elton John to be one of her son's godfathers

Christenings may have dwindled but the number of godparents per child has increased. Prince George will have seven. Elizabeth Hurley's son apparently has six godfathers.

And it's not just a celebrity fad.

"In practice it seems to be changing," says the Archdeacon of Leicester, Tim Stratford, although there's been no doctrinal change. That's because both the Church of England and the Catholic Church only have minimum requirements, of three and one respectively.

"It used to be the minimum that was the issue," says Stratford. "Now the issue for a lot of clergy is that often people are choosing a lot of godparents.

"The registers we have, for instance, often only have four spaces to put godparents' names but people may be choosing six or eight."

3. …who are not necessarily religious

A godparent is supposed to mentor the child in their faith. And the rules haven't changed.

"Because of what godparent strictly means, we only have practising Catholics as godparents, and fellow Christians as 'special witnesses'," says Fr Paul Keane, a parish priest in Essex.

The Church of England does not distinguish between denominations, says Stratford.

"The only requirement for godparents is that they should have been baptised. A Muslim or a Hindu cannot strictly speaking be a godparent, nor can a secularist who has not been baptised."

While the Church does insist on godparents being baptised, external, that may not be uniformly enforced across all parishes.

Stratford acknowledges that in practice the godparent's role is broader than just a religious one.

"Providing the child has enough godparents, there's nothing to stop people being 'honorary godparents', without technically being one. That is fairly common in the Church," he says, explaining that the Church is soon to advise using the term "supporting friend".

"It's the Church trying to catch up with emerging trends in society."

If godmother doesn't fit, how about "fairy ungodly mother"?

4. The rise of baby-naming ceremonies

People may be less religious but many are reluctant to relinquish all church traditions.

"Naming ceremonies are on the rise and are something that we would probably expect to see increase in the coming years," says Sarah Barrett, managing editor of parenting website BabyCentre.

These were almost non-existent about 15 years ago but now there are hundreds every year, according to the British Humanist Association, external.

"The lack of religious belief is why they're becoming more popular," says Barrett, with many enjoying "the idea of officially welcoming the baby into the world and introducing them to friends and family".

And while they may have rejected religion, they haven't rejected religious terminology. "'Godparent' is a much easier term to explain to people than 'supportive mentor'," says Barrett.

Plus, Marlon Brando has never portrayed a "supportive mentor".

5. Children baptised later in life

Geri Halliwell's daughter Bluebell Madonna was christened at 11 months old

In 1992, almost 80% of Church of England baptisms were of babies under a year old. By 2011 this had dropped to about 60%. One in three Church of England christenings is now of a child between the ages of one and 12.

"Traditionally christenings took place when the child was a baby but now more and more parents are waiting until they've had a second child and then getting both christened together," says Barrett.

Sort of like a two-for-one deal. But it's only partially about cost, she says. "Parents like to do it when the child will perhaps remember the ceremony."

6. "Bogus" baptisms

High competition for school places is credited with creating a new phenomenon - the "bogus" baptism - where the primary motivation is to get a child into a faith school.

"To be sure that I could have the privilege of having my son going to my local state school I had to pretend to be an Anglican," says atheist Andrew Penman, author of School Daze: My Search for a Decent State Secondary School.

"It wasn't something I did for kicks or to undermine anyone else's faith. I did it under duress because that's really the only way I could be sure of getting into my local state school," he says, adding that he felt "embarrassed" and "awkward" during the ceremony.

Penman feels the practice is widespread, indicating that the numbers of people attending church "fall off a cliff after the children get past the threshold at which they either get or don't get a [school] place".

The word "bogus" is a bit strong in her case, says Jane, who prefers not give her real name. A lapsed Catholic with a non-religious Jewish husband, she says she'd always wanted her children to have a religious grounding.

"But I'd be lying if I said I didn't have the idea of schooling in my head. The most 'bogus' aspect is the time pressure," she says, admitting that she baptised her second child much earlier than her first after reading a parish newspaper warning that Catholic schools would be making the entrance criteria more stringent.

"[It said] it would be a good idea to get your child christened in the first four months of their life," she says.

It's difficult to gauge how widespread the practice is. Keane thinks that, if it's an issue at all, it's most likely to be in areas where Christian schools are oversubscribed, such as London.

Both he and Stratford think that the preparation time and public nature of services mitigate the likelihood of large numbers doing so.

"My experience has been that parents invariably wanted to mean what they were saying," says Stratford.

7. Christening gowns are out of fashion

George will be baptised in a replica of the same traditional white christening gown as his father and every monarch since Edward VII. But it's an increasing rarity.

"Christening gowns are a bit out of fashion right now," says Barrett.

"At [the baptismal] classes we were told that you no longer have to dress your child in a traditional gown," says Becky Bevis, who has a 13-month-old son. "He wore a white shirt and some baby chino trousers." None of the other four children baptised that day wore a gown either, she says.

"What the Church simply asks is that the child is wrapped up in a white garment as a sign of their new life with Christ after they're baptised," says Keane.

"Unless you've got an heirloom or a family tradition of passing down the christening gown, such as the royals, lots of mums will get their children dressed in cute outfits, pretty outfits, or christening nappies," says Barrett.

8. But gifts are not (although they're not always silver)

Christenings are big business. Designers such as Vera Wang have got in on the action, while John Lewis witnessed an 8% growth in christening gift sales in the past year.

Although the tradition for silver gifts still prevails, it seems to be less strictly adhered to.

"We didn't receive any silver," says Bevis of her son's baptism, while she received a silver spoon for her own christening three decades ago.

The penchant for silver rattles is waning, says Barrett.

"Now planting trees is quite popular as a christening gift, as are things that you can give to the baby that are for future years," she says. "Some people give whisky that is meant to be drunk when the child reaches 21."

Even those sticking to traditional silver may be cutting corners. Of John Lewis's premium christening gifts, only 55% were actually silver plate, with 40% pewter and 5% stainless steel.

9. The christening water is warmed

Babies may still cry from time to time, but it's far less likely to be the shrill shriek after being doused in freezing water.

"Water's being warmed up in the fonts these days simply because churches can do it," says Stratford. "You wouldn't have to go very long ago to find most country churches having no electricity. How then would you provide warm water? It's got to be a relatively new phenomenon."

Some rural churches may not yet have the capacity. "More and more churches are putting kitchens in so it's possible to boil a kettle and warm the water up," he says.

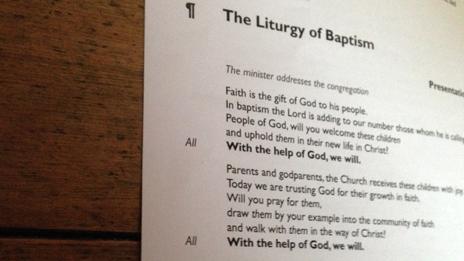

10. Simpler language

The Church of England is still developing its language for the service.

Until 1980 christening services were still given in 17th Century language. But while the Alternative Service Book introduced modern language, it provided "quite a thin service, with short questions and fewer [of them]", says Stratford.

The Common Worship, introduced in 2000, hasn't pleased everybody. "The clergy thought that the language was too complex, [as were] the services themselves."

It prompted the general synod in 2011 to agree new language was required, although the specifics have not yet been agreed.

"It's not a dumbing-down of the language or the use of colloquialisms," says Stratford, nor about brevity or a loss of poetry, but about making the language less high-brow.

Questions over the use of the word "submit" - as in "Do you submit to Christ as Lord?" - were also raised.

"It felt quite inquisitorial," he says. "It was not easy for a lot of people to respond to that question because it was felt that 'submit' meant giving up and communicated the wrong meaning."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external