Lockerbie bombing: 'It took 24 years to find out my son had died'

- Published

Carol King-Eckersley, who discovered the son she gave up for adoption had died in the Lockerbie bombing: "I didn't have him with me physically. He was always in my heart"

Carol King-Eckersley's son was one of the 270 people killed in the 1988 bombing of Pan-Am flight 103 over Lockerbie but it was only this year that she found out he had died.

When her husband died last year Carol King-Eckersley underwent grief counselling and, as part of the process, decided to search for the son she had given up at birth when she was just 19.

She knew the name of the boy, but for 45 years she had kept her promise not to look for him or interfere in his life.

When she searched the internet, her hopes of a reunion with her long-lost son were dashed. She discovered his name on a remembrance page for those killed in the Lockerbie bombing almost 25 years earlier.

"270 people died in that tragedy and one of those happened to be the only child I ever had. And I didn't even know it until last April," says King-Eckersley, now 65. "So it became a kind of double tragedy. I found him and I lost him on the same day."

Her son, Kenneth Bissett, had been a Cornell University junior studying with Syracuse University's overseas programme in London. He had been due to fly home a few days earlier but stayed in London for a 21st birthday party arranged by friends.

Instead, he caught the flight from London to New York on 21 December 1988. It exploded over Dumfries and Galloway, killing everyone onboard and 11 people on the ground in the Scottish town of Lockerbie.

"I'm still in the semi-numb part after you lose a loved one," says King-Eckersley. "Even though I didn't have him with me physically he was always in my heart. I thought of him pretty much every day."

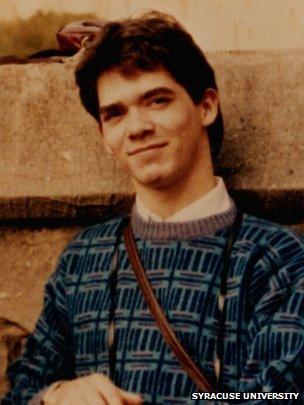

Kenneth Bissett was studying in London

She says she cannot imagine the "devastation" experienced by his adopted parents, Florence and John, who have since died, and she thinks that her own suffering may have been "softened" a little by never having had her child with her.

"I'm just starting to get to know him," she says. "In a way I'm going backwards because the getting to know him makes it sharper, makes the regret deeper."

She adds: "I saw a baby picture for the first time the other day. I had never seen him except for wrapped up in a yellow blanket on the day we left hospital and the attorney was taking him to his new parents."

Back in 1967, Carol King was the daughter of a high school principal when she became pregnant. She says she gave up her son for adoption to protect her father's reputation rather than her own.

At the time it would have been thought that he could not protect other children in his school if he had failed to stop his daughter from getting pregnant out of wedlock.

The last time she saw Kenneth, he was in the front of the car of the attorney who had arranged the adoption.

Carol King-Eckersley aged 20

She was being taken from the hospital where she had given birth to her sister's house where she had been staying during her pregnancy. The child would not be getting out of the car when she reached her destination.

"There was this little bundle wrapped up in the front seat and all I could think, all the way from Queens in New York to mid-Manhattan, was 'please don't cry'," she says.

"I knew that if he cried I would not be able to do it. I never held him but now I get to grieve for him."

In October, Ms King-Eckersley attended Remembrance Week, an annual event at Syracuse, the New York state university which lost 35 students in the Lockerbie bombing.

She says the service made her realise she had been living with the "stigma" of giving up her child and she found it hard to feel she "belonged" among the parents who were grieving for their lost loved ones.

However, her sister convinced her to get involved and take her place alongside the other parents. "It was such an amazing feeling for me to be included and feel like Ken and the other kids were guiding the whole thing in some way," she says.

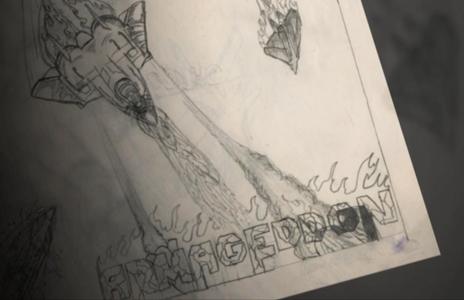

At the Syracuse memorial she met friends and classmates of her late son who told her stories about their time with him. "From everything I have heard and read he was an absolutely brilliant young man with a marvellous sense of humour.

"He was also an incredible artist. I saw a comic strip that he drew when he was 11 years old."

Eighteen months before Lockerbie an American warship patrolling in the Gulf shot down an Iranian passenger jet after apparently mistaking it for an F-14 fighter.

Kenneth's cousin told King-Eckersley that her son had drawn an aeroplane exploding in mid-air and told his adopted parents "we are going to pay for this".

King-Eckersley was unable to have more children but she did adopt her late husband's son, Ray. "One of my dreams was to introduce him to his brother but now I won't be able to," she says.

Throughout all the years she did not know of Kenneth's death, she says she dared to dream she would meet him again.

"There was always the hope and dream that some day there would come a knock at the door and I would open it and there would be this tall handsome gentleman saying, 'Hi, I guess you are my mom'," she says.

"When I saw that on my computer it was like somebody had turned out a light because that hope was gone."

Living With Lockerbie will be broadcast on Monday 16 December at 22:35 GMT on BBC Scotland and on Saturday 21 December at 09:10 GMT on BBC World News. The programme will be available on the iPlayer.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external