How is the NSA’s vault of secrets being unlocked?

- Published

Glenn Greenwald is the lead reporter on the Snowden leaks

Media organisations have revealed startling details about US espionage in recent weeks. The disclosures can be traced back to three people who don't play by the rules - intelligence leaker Edward Snowden and his chief disseminators, the Guardian newspaper reporter Glenn Greenwald, and independent film-maker Laura Poitras.

The National Security Agency (NSA) reportedly collected data on millions of US customers of Verizon, a telecom firm, and on 60 million calls in Spain. It is also said to have obtained data on 70 million digital communications in France - and spied on Chancellor Angela Merkel for years.

The revelations, which appeared in articles co-written by Mr Greenwald or Ms Poitras in the UK's Guardian newspaper, French paper Le Monde, Germany's Der Spiegel and two Spanish newspapers, El Mundo and El Pais, shed light on an organisation which, as experts explain, is even more shadowy - and hard to cover - than the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

The media reports have unnerved diplomats, spies and politicians. In August UK authorities detained Greenwald's partner, David Miranda, at Heathrow Airport - and confiscated Snowden documents he had been carrying.

"Disclosure of any information contained within those documents would be gravely injurious to UK interests, would directly put lives at risk and would pose a risk to public safety and diminish the ability to counter terrorism," said a detective, according to Reuters, external.

On Monday, a European delegation went to Capitol Hill in Washington to talk with US lawmakers about the spy programmes.

Meanwhile the man who has been masterminding the release of the documents about the NSA - and disrupting the schedule of world leaders - was on a Brazilian road, talking on his mobile and complaining to the BBC about a lousy phone connection.

Mr Greenwald says that Brazilian telecommunications are spotty. "It is almost like pot luck," he says. In addition he has security measures for his phone. "Sometimes that makes it harder," he says.

The security precautions make sense, given that quite a few people would like to listen to his conversations. As Mr Greenwald tells the BBC, the revelations about the NSA are based on documents obtained by Mr Snowden, the former contractor who is now in hiding in Russia.

There are apparently tens of thousands of documents, many of which have not yet been published. They include details about NSA activities, US military intelligence and methods used to eavesdrop on embassies and missions.

And they are not all about US operations. A former UK official says that Greenwald has 58,000 top-secret British security documents, according to the Independent, external.

As one expert, Steven Aftergood, the director of the Project on Government Secrecy at the Federation of American Scientists, says: "The Snowden collection is the mother lode."

Information from German Chancellor Angela Merkel's phone was apparently collected

Mr Greenwald says that he and Ms Poitras are in charge of the documents, and that they decide how and when the documents are disseminated.

"We each have a complete set, and Snowden is not the one making the decisions," he says. "That's Laura and myself."

Their goal, he says, is simple: "We want to inform people about what's being done to privacy."

Mr Greenwald is the journalist who has garnered the most attention for his dealings with Mr Snowden, but he is not the only one. The Washington Post's Barton Gellman, was also given documents - that may or may not be the whole set - which he used for his work, external on an internet surveillance program called Prism.

Representative Mike Rogers, centre, spoke with Europeans about eavesdropping

Mr Greenwald says that he tries to give the documents about the NSA to reporters and editors at influential media organisations so that the stories will have the biggest possible impact.

Mr Aftergood explains: "He is releasing them strategically in different parts of the world."

Mr Greenwald admits, however, that the process is somewhat ad hoc. He works with journalists at Le Monde and other media organisations to report on a story. When the piece is ready, he says, they publish it.

"The process for deciding what gets published is not all that refined," he says. "It's not necessarily a scientific formula."

Sometimes he makes mistakes. Le Monde's article, external, written under the bylines of Mr Greenwald and journalist Jacques Follorou, gives an account of alleged US eavesdropping operations in France.

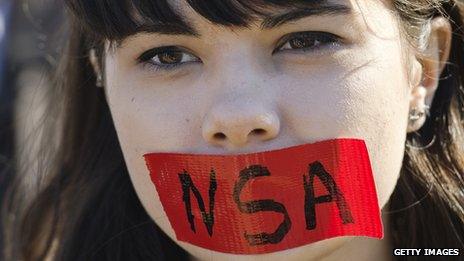

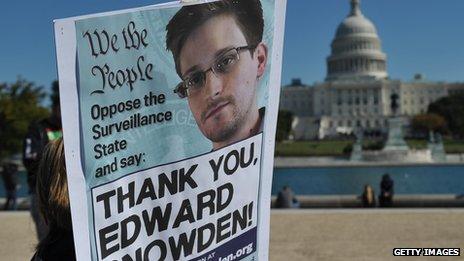

People in Washington and other cities have protested against NSA operations

After the story appeared, a US official, James Clapper, the director of national intelligence, fired off a statement saying that the newspaper provided "inaccurate and misleading information".

"The allegation that the National Security Agency collected more than 70 million 'recordings of French citizens' telephone data' is false," he wrote.

Mr Greenwald says that he believes the newspaper may have inadvertently said the NSA was monitoring calls - when in fact the agency was collecting metadata, which includes information such as the place where someone logged on to their email account.

"That's the confusion," he says.

He seems unfazed by the glitch. For Mr Greenwald, releasing the documents and having this kind of impact on the world - the New York Times' Bill Keller wrote in an article, external that he broke "what is probably the year's biggest news story" - has been a heady experience.

Many of the disclosures have come from Edward Snowden

Mr Greenwald sounds giddy on the phone, describing his accomplishments in journalism and his new media venture with eBay founder Pierre Omidyar. Mr Greenwald announced recently that he will leave the Guardian in order to work on a general-interest news site backed by Mr Omidyar.

Mr Greenwald explains that he will continue to publish documents about the NSA in conjunction with other media organisations. He sounds confident that his work will continue to have an impact - and reminds the BBC reporter on the phone that Mr Omidyar is one of the "richest men in the world".

"I don't feel like I'm leaving the Guardian to work for some obscure website," Mr Greenwald says. "I'm not worried about our ability to be heard."

He has the attention of the world - though like other journalists he is also at the mercy of modern telecommunications. A moment later the phone signal gets weak - and his voice is cut off.

Update: NSA director Gen Keith Alexander said on Capitol Hill , externalthat reports about their collection of European phone records are "completely false".

A summary of US spying allegations brought about by Edward Snowden's leak of classified documents