Press regulation: The 10 major questions

- Published

The Royal Charter on press regulation is expected to be approved later. What are the major questions that have defined the debate?

Why is this happening?

When news emerged in July 2011 that murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler's phone had been hacked by the News of the World, Prime Minister David Cameron set up a public inquiry into press ethics.

Between November 2011 and June 2012, (the then) Lord Justice Leveson's inquiry heard evidence from dozens of witnesses who had apparently been the victim of phone hacking and intrusive behaviour. JK Rowling revealed that a journalist had tried to contact her by putting a note in her five year-old daughter's schoolbag.

Sheila Hollins related how reporters had hounded her daughter Abigail Witchalls after she'd been stabbed in the neck and paralysed.

In November 2012 Leveson published a 1,987-page report calling for a new system of press regulation. The report said some elements of the press had "caused real hardship, and on occasion, wreaked havoc with the lives of innocent people whose rights and liberties have been disdained".

The light-touch Press Complaints Commission (PCC), run by the newspaper industry, was regularly ignored by journalists, Leveson's report said.

Leveson proposed a new self-regulating body to be overseen by a watchdog - known as a recognition body - that would be free of press or political control. The three main political parties accepted Leveson's main recommendations.

But David Cameron - uncomfortable with the idea of state interference in the press - rejected the idea of legislation to underpin the new system of regulation. The compromise solution was a Royal Charter. The final draft of this document is going to the Privy Council for formal approval.

Is there any difference between a Royal Charter and a press law?

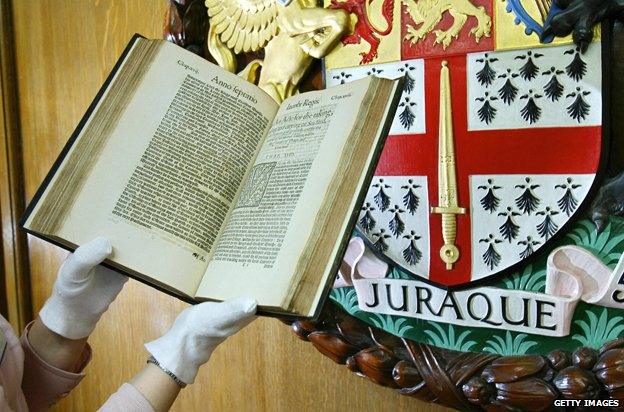

A legal volume dating from the 13th Century in the Law Society's library

A Royal Charter is an unlikely way to regulate the press. It is often described as a medieval form of documentation, used to set up universities, oversee the BBC, and turn towns into cities. The Royal Charter on self-regulation of the press does not in fact spend much time detailing the work of the regulator. Instead it sets out the work and structure of the recognition body that is supposed to guarantee the self-regulator does its job properly.

Royal Charters are approved by the Privy Council, external, which in effect is a body composed of ministers rubberstamping decisions that have already been taken.

The charter begins with the sentence: "Elizabeth The Second by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and of Our other Realms and Territories Queen, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith: To All To Whom These Presents Shall Come, Greeting!"

But despite what one paper called its "flummery" the government spotted advantages to a Royal Charter. While an act of parliament can be amended with a simple majority, it was possible to insert a clause in the Royal Charter requiring any changes to be approved by a two-thirds majority.

What's the difference between what the charter proposes and the existing Press Complaints Commission?

The PCC would be replaced by a new regulator with beefed up powers, and a watchdog - the recognition panel - to check the regulator remains independent. The regulator would be set up by the press. To ensure it remains impartial, it must meet certain criteria. Board members would be chosen by an independent appointment panel. Like the PCC, a majority of members would be non-journalists. But crucially, there would be no serving editors on the board. In contrast, seven out of the PCC's 17 commissioners are serving editors.

The new regulator would have to draw up a standards code. It would be advised by a code committee on which serving editors have "an important part to play" but not a decisive one - the final decision on what is in the code lies with the regulator's board. The code must protect freedom of speech. It would cover how journalists behave in getting hold of information, their respect for privacy when there's no public interest justification, and accuracy.

The PCC has an editor's code but no powers to fine those who break it. In contrast, the new regulator could impose fines of up to 1% of turnover, capped at £1m. The regulator would also provide a speedy arbitration service - with a small administration fee - to deal with complaints. Meanwhile, the recognition panel would be made up of between four and eight members. None can be journalists, civil servants or MPs. They would serve five-year terms, able to be extended for another three years.

Is it compulsory? What happens if they don't sign up? What's the timeframe?

(l-r) Alan Rusbridger, editor of the Guardian, and Paul Dacre, Daily Mail editor

Media organisations will be free to sign up or stay outside the new system of regulation. But there are incentives designed to make the new system attractive, which opponents say amount to a "stick" to force the press to sign up. And, controversially, those incentives have already become law. The Crime and Courts Act 2013 advises courts to treat publishers differently - in a libel case for instance - according to whether they are part of an approved regulator or not. Publishers outside the regulator run the risk of exemplary damages if they lose a case. Most controversially, they will usually have to pay a complainant's costs even if they (the newspaper) win the case.

By contrast, news organisations under the Royal Charter system go through the arbitration system with any complainant. This protects them from heavy costs or exemplary damages. If the complainant opts to go to court rather than first try arbitration, the judge is advised to expect the complainant to pay the media organisation's costs. Supporters, such as Steven Barnett, professor of communications at the University of Westminster, say that there has to be some kind of carrot to get the press to sign up.

And the new system will protect the press from a longstanding grievance - the ability of rich and powerful individuals, such as Robert Maxwell, to threaten papers with financially ruinous legal action. But freedom of expression organisation English Pen is worried by the punitive element. "It will create a chill for publishers like Private Eye who on principle won't join," says Jo Glanville, the group's director. "They've done everything they can to avoid creating a compulsory regulator but in the end it's a compulsion of a kind."

Private Eye reporter Adam Macqueen says the magazine's staff were bemused by the Leveson report. "He was very complimentary about Private Eye and the Street of Shame column." But then in his conclusion he said it should join the regulator or risk paying the price in higher costs and exemplary damages. "I don't see why Private Eye should be forced to sign up when we've probably done more to investigate the press over the last 40 or 50 years than anyone else," he says.

None of the newspapers have committed to a new regulator so far. The timescale doesn't envisage anyone signing up yet, counters Brian Cathcart, founder of the Hacked Off campaign. "It will take several months to set up the recognition panel in full. Until then no self-regulator can be approved."

But what happens if a stand-off develops? Elements of the press are applying for a judicial review to prevent the Royal Charter taking effect. The move is being led by Pressbof, the industry body that funds the PCC. Pressbof's chairman, Lord Black of Brentwood, said: "The government and the Privy Council should have applied the most rigorous standards of consultation and examination of the Royal Charter proposed by the industry, which would have enshrined tough regulatory standards at the same time as protecting press freedom. They singularly failed to do so, and that is why - as the issues at stake are so extraordinarily high - we are having to take this course of action."

A spokesman for the Department of Culture, Media and Sport says the judicial review will not delay the Royal Charter's progress. "The Royal Charter will be granted then sealed and the recognition body will be set up. It's for the press to set up the self-regulator."

If after a year there is still no regulator in place, the recognition panel will be asked to report back to Parliament and the Scottish Parliament, the spokesman adds.

What do newspapers want to do about it?

The newspaper industry has put forward an alternative proposal for self-regulation based on the Leveson report. It has been rejected by the Privy Council. There were several key differences between the government and the press systems.

In the press industry version, former editors would be allowed to sit on the recognition panel. No changes would be allowed by Parliament, even with a two-thirds majority. On apologies, the press regulator - to be called the Independent Press Standards Organisation (Ipso) - would have less power, able to require prominent apologies rather than to "direct" them.

The complaints arbitration service would go ahead subject to a pilot programme. And one of the members of the appointments committee could be a serving editor or MP, unlike in the official Royal Charter. The press says this would make for a more realistic charter and protect press freedoms. But the plan was rejected by the Guardian, external and by the Hacked Off group. Cathcart said the newspaper proposals were not serious about tackling press wrongdoing. Ipso, like the government backed version, allows for newspapers to be fined up to £1m. "They say no fine can be imposed without investigation of the problem, which seems fair. But Ipso's investigation of the problem is fantastically complicated," suggests Cathcart. It's unlikely that any serious investigation could ever be completed, he argues.

Could MPs interfere with the Royal Charter to crack down on the press?

It would be very hard, supporters say. A clause in the Royal Charter states that only a two-thirds majority of parliament can amend the document. This is backed up by a provision in the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013, external.

It states that the Royal Charter must not be altered unless the changes are in accordance with the terms of the charter - in other words that there has been agreement by two-thirds of Parliament.

All this is intended to reassure the press that politicians will stay out of press regulation. But parts of the newspaper industry remain sceptical. A Financial Times editorial, external warned of dangers: "It is true that any changes theoretically need a two-thirds majority in both Houses of Parliament, but this same requirement is rooted in an act of Parliament that can be amended by simple majority." Andrew Gilligan, senior reporter at the Daily and Sunday Telegraph, agrees. "Any future government can simply change the two-thirds majority rule," he says.

A simple majority of MPs could repeal the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013. Then the Privy Council, which is controlled by the government, could amend the Royal Charter. The question is how realistic is such a scenario? Gilligan says it could happen. In the aftermath of an atrocity, it is feasible that the government could insist on cracking down on press revelations to preserve national security. The government's displeasure at the Guardian's release of data from the US National Security Agency shows how such a situation could develop, he argues.

But Barnett, who supports the Royal Charter, says the government would never dare try to intervene on the independence of the press. "It could never happen. Partly because there's no appetite for curbing free speech, and partly because there'd be such an outcry not just from the press but from those campaigning for accountability," he argues.

Could the regulator prevent a paper from publishing a story it doesn't like?

No. The Charter states that the regulator's board cannot prevent publication from going ahead. "The Board should not have the power to prevent publication of any material, by anyone, at any time although (in its discretion) it should be able to offer a service of advice to editors of subscribing publications relating to code compliance."

Will websites/blogs etc be covered?

It depends. If they "contain news related material", have more than one author and are a commercial operation they will probably be part of the new system. They will then have to decide if they want to join the regulator. What about blogs? They are only considered "relevant publishers" if they have 10 or more employees and an annual turnover of £2m. Charities and scientific journal websites will not be covered. Leveson's proposals fail to understand the way the online universe is taking over from the print world, Hugo Rifkind has argued in the Times, external.

"When newspapers exist only online, when your daily print run has morphed into the daily broadcast of an iPad app, why not broadcast it from somewhere beyond regulation's reach? Personally, I like the idea of pirate newspaper ships, beaming news from just offshore." Some sites like that of political blogger Guido Fawkes use foreign servers and base themselves abroad, in his case in the Republic of Ireland. The DCMS says the location of the servers is not relevant.

"What is relevant is whether the alleged libel (or other relevant media related offence as covered by the new provisions) was committed here eg the article was published here. Downloading here can count as publication in the law. The new provisions do not alter the way that libel and other media laws apply in terms of jurisdiction."

Who can complain about press intrusion?

Hugh Grant, Sienna Miller and Steve Coogan have all complained about press intrusion

Under the PCC, only people directly affected by a story could complain. The Royal Charter widens that beyond people personally affected to include third parties "seeking to ensure accuracy of published information". There will be no charge to bring a complaint, a move designed to give ordinary people the right to complain.

Gilligan fears that the new system would encourage anyone with any grievance to make a complaint, however ludicrous. It will inevitably bog down newspapers in time-consuming complaints processes, he says. "Everyone offended about anything will be given carte blanche to complain," he says.

Cathcart says the change to give third parties the right to complain was starting to happen under the PCC towards the end. He welcomes it. "It is right that if newspaper says 'Muslims do this', that a Muslim organisation should be able to say, we're not directly affected but we think you should take this as a complaint. There's been far too much [press] generalisation that has been immune from PCC action." The regulator can reject complaints that are based on opinion or lobbying, he adds.

Is the freedom of the press going to be damaged?

The prime minister has denied, external that the Royal Charter crosses a Rubicon by bringing in state regulation of the press.

But Gilligan says a line has been crossed. "A new press regulator will not be part of the state but will have to conform to fairly prescriptive regulations set by the state in the Royal Charter." That is a big change in how British journalism works, he believes. If the two-thirds majority is repealed, an authoritarian government could begin clamping down on precious freedoms, he argues. Hacked Off responds that the government can do that already, not by fiddling with a Royal Charter but by passing laws.

Gilligan says that even without a malign regime in power, there are dangers. The tone of the Royal Charter misunderstands how journalists work. "They think an article should be produced calmly and coldly almost under laboratory conditions. You shouldn't be subjected to the same standards as law or academia when they have months to get things right."

A big scoop might get the odd small detail wrong in the cause of a much bigger story with genuine public interest, he says. The danger is that soon papers will be forced into grovelling front page apologies. It's humiliating for papers and prevents them from focusing on the big story, he warns. They may still run the big scoops like MPs expenses. But investigations into a less accessible subject, such as Islamist extremism may not be worth the risk, he says.

There's a sense that people are trying to regulate newspapers like schools and hospitals, Gilligan suggests. "Everyone agrees what a good school or hospital is. Not everyone agrees what good journalism is." Tabloid journalism can be cruel but the crooked and corrupt deserve it, he argues.

Macqueen says that how public interest is defined will be crucial. When the Daily Telegraph first published its expenses story, some MPs claimed it was not in the public interest, he says.

Barnett says it is wrong to say the Royal Charter crosses a new line. There are already reams of legal controls - defamation, contempt of court and national security laws - that constrain what journalists can publish, he argues. "The notion that we are free to publish anything whatever harm might come is not true in this country or any other, including America." He says the new system will "promote good journalism" and protect the press from litigious groups of people. It will also give people wronged by the press a chance to set the record straight. "We need the recognition body because the last 80 years is a cycle of repeated abuse." A graphic example is the story of how a tabloid journalist dressed as a doctor to take photographs of Gordon Kaye in hospital following a car crash, he says.

During Sir David Calcutt's inquiry into the behaviour of the press, the newspaper industry begged for one last chance at self-regulation, he says. They got it. But yet again it failed, he argues, even before phone hacking came to light. "The PCC code was repeatedly breached. Countless stories were hopelessly inaccurate about ordinary people. They couldn't get an apology or correction."

And Barnett disputes the idea that the power to direct apologies will have a chilling effect on investigative journalism. "A self regulator will understand the wider importance of watchdog journalism. It's all about trying to promote good journalism."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external