10 ways to prevent plane bird strikes

- Published

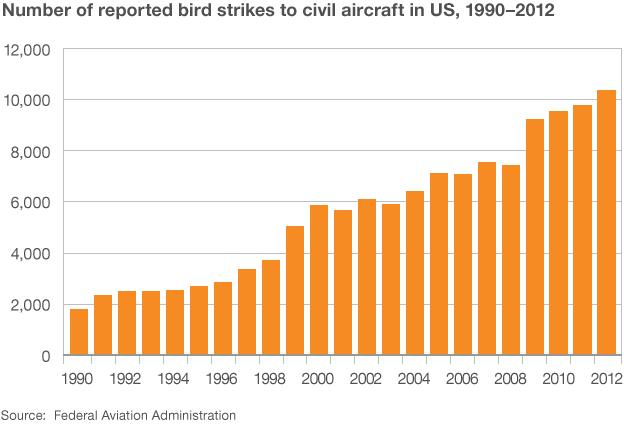

Hardly a week goes by without a plane somewhere in the US making an emergency landing after hitting birds. As these incidents reach record levels, airports are coming up with increasingly imaginative ways of combating them.

A Southwest Airlines plane recently made an emergency return to Tennessee's Nashville International Airport after hitting birds at take-off.

There was a similar incident at Chicago's O'Hare Airport a few weeks ago and another involving an Alaska Airlines flight that made an emergency landing in Oakland while en route to Honolulu.

According to a report by the Federal Aviation Administration, the number of bird strikes has increased nearly six-fold since 1990 to a record 10,343 in 2012.

This is blamed on four factors. There are larger populations of some of the birds responsible - for instance, there are twice as many Canada geese in North America now as there were in 1990. And many birds find airports to be attractive habitats.

There are also more flights, quieter engines and greater awareness which has meant more rigorous reporting. After a US Airways plane was downed by geese and had to land in the Hudson in New York in 2009 - making pilot Chesley Sullenberger an overnight international hero - reports of bird strikes spiked.

But in recent years, bird-strike damage to aircraft in the vicinity of airports has fallen, because of success in dispersing the birds, and improving aircraft design. Here's a selection of methods already used or in the pipeline.

1. Every airport in the US, and many more across the world, use pyrotechnics daily to drive the birds away, says Michael Begier, national co-ordinator of the airport wildlife hazards programme at the US Department of Agriculture. "The flash, bang kind of stuff immediately gets their attention and pushes them away." Bangers and screamers make a loud explosion, others make a whistling sound, while some emit sparks - different birds respond to different things and some even take flight at the mere sight of the wildlife vehicle. A banger shot from a pistol cartridge can travel 30-40 yards before exploding, while a 12-gauge shotgun can reach 70-100 yards. Waterfowl respond fairly well and after two or three times they relocate. Raptors can be harder to move.

Airport biologist Odin Stephens deploys pyrotechnics at a military airbase

2. A population of Canada geese used to live between the two runways at Salt Lake City. Not any more, says Gib Rokich, who oversees the airport's wildlife programme, due to a system of egg addling. "The goose is scared from the nest and the eggs are addled or oiled pretty much in place by picking each egg up individually and shaking them or submerging them in vegetable oil. The goose continues to sit on them but they never have a successful hatch. If she lays 10 goslings, and five survive into adulthood, then they will want to come back to the same location to nest, so you can see how it can multiply. After four years, we broke the cycle, so we still get the occasional one but they're not established any more."

3. Bird distress signals are a pretty effective way of dispersing species that cause these problems, says David Randell, director of Scarecrow, which provides systems to 20-30 British airports. Speakers mounted on a car emit the sounds of up to 20 different species, operated by a driver using a tablet-style device.

Sky's job description - chase birds

4. A border collie called Sky has been chasing birds for five years at Fort Myers, Florida. Since 1999, when dogs were first used, there has been a 17% drop in bird strikes. While the egrets, herons and moorhens can get used to pyrotechnics, they never adapt to the presence of a natural predator like Sky, says Ellen Lindblad, director of planning and environmental compliance at Southwest Florida International Airport. "She seems to love it, day after day. This is what border collies are bred for."

5. Pigs have been used to disrupt the habitat of the 10-15 California gulls that used to routinely fly over Salt Lake City airport twice a day. Wildlife services had tried harassing them without success, then someone came up with the idea of putting pigs on their island habitat, adjacent to the airport. The pigs trampled and ate the gulls' eggs and are now used for a few weeks every spring as a deterrent. The migrating gulls arrive, see the pigs waiting to eat their eggs, and then go to another location.

6. Eliminating vegetation removes a food source for birds and deters them from settling. At Salt Lake City, 70 acres of grassland was replaced this summer with ground-up asphalt. Grasshoppers, gnats and armyworms attract rodents which in turn attract raptors. An airport in Sandusky, Ohio, has experimented with different types of grass, to identify which mix is least attractive to Canada geese.

7. About 300-500 raptors are trapped and relocated each year at Salt Lake City, including red-tail hawks, barn owls and peregrine falcons. Some traps use a rodent to entice the bird and catch their feet in a noose. Others are self-operating, built on top of pigeon coops to attract larger birds - they swoop in, and a door slams shut behind them.

8. A chicken gun is used to test the durability of aircraft windscreens and engines. A thawed chicken is fired out of the gun using compressed air, in an effort to simulate the impact of a bird hitting the plane in flight.

9. Lights on aircraft could be used to increase their visibility to birds, says Begier. The idea is to manipulate the characteristics of the light by varying the pulse rates and wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum and tune these changes to specific bird species. The lights would provide an earlier warning so the birds can detect and avoid the aircraft. Some of these changes to the light might be imperceptible to humans. Evidence collected from dead birds in airports suggests they were trying to evade the planes when they were hit. "We realised that the birds are trying to make the right decision but don't have enough time so what we are trying to do with the light research is give them that time."

10.The Dutch air force is using a bird detecting radar that could eventually be adopted by civil aircraft. "We've known since WWII that radar can see birds, when they were coming across the Channel and they figured it was birds and not German bombers," says Begier. These bird detecting radars are small and mobile, and technology has come on in the last 10 years, but they can't yet identify the species or numbers. "The ability to delay a commercial flight with technology that's not quite there is the problem."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external