How dangerous is it to play on after being knocked out?

- Published

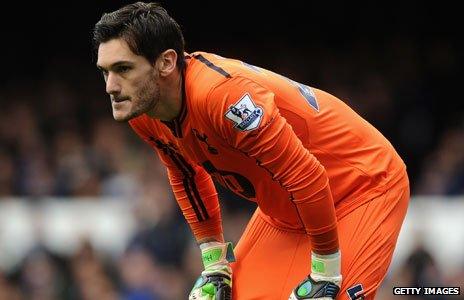

Tottenham Hotspur goalkeeper Hugo Lloris was temporarily knocked out on Sunday before returning and completing the match. How dangerous is it to play on after being knocked out?

The clash with the knee of Everton striker Romelu Lukaku was enough to force Lukaku off injured. But Lloris played on and went on to make a crucial save to keep the score at 0-0.

The decision to allow him to continue has since been labelled "irresponsible" by brain injury charity Headway. FIFA's chief medical officer Jiri Dvorak said there's a "99% probability that losing consciousness in such an event will result in concussion".

But Lloris had a CT scan after the match and showed no signs of concussion, according to the club.

So did the medical team get lucky or could they make an accurate assessment on the ground?

"Once the relevant tests and assessments were carried out we were totally satisfied that he was fit to continue playing," said Tottenham's head of medical services Wayne Diesel, on the club's website.

When a player is knocked unconscious, medics refer to the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool (Scat) or the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), says Gemma Davison, a former paramedic and a director of Firstaid4sport.co.uk.

The latter gives an indication of how severe the head injury may be through a scoring system out of 15 - testing the individual's motor response, verbal response and eye opening.

The whole process can take less than five minutes, she says.

But there's a limit to what can be gauged from on-field inspections.

"The risks are that even if no significant head injury is immediately apparent, there can be bleeding or swelling occurring in the brain that can result in damage if left untreated," says Davison.

"Given that Lloris was knocked out, it clearly indicates a brain injury," says Prof Mike Barnes of the UK Acquired Brain Injury Forum. "By definition, if you're knocked out you've injured your brain."

And it's impossible to decipher the internal damage from the side of a pitch, says Barnes, "even if 90% to 95% of the time it will be perfectly fine".

"A sensible medic should have said, 'Sorry, you've got to come off,'" he says.

It can take several hours for any signs of damage, so the safest thing to do would be to keep a player under observation, he says.

Concussions have been in the news recently after Dr Barry O'Driscoll quit his International Rugby Board post claiming the body trivialised concussion.

"A concussion is concussion, whether it's in rugby, football or walking down the street. The risks are the same," says Luke Griggs of Headway. "People often think that for any significant damage to be done it must be a really severe blow to the head - that's not the case."

Many observers expressed admiration for Lloris' desire to return to the field, something manager Andre Villas-Boas acknowledged helped to convince him that he was OK to continue.

"It cannot be right that a player makes a decision whether he's fit to play, not in this day and age," says Griggs. "We're more evolved than that and it should be taken out of the hands of the player - and the manager."

"We're not talking about a potential concussion here - we're talking about the fact that he was actually unconscious."

"It was an unnecessary risk," agrees Barnes. "If you're knocked out you ought to come off. There are no signs on the pitch that you can tell whether he's going to be fine or not."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external