Degenerate art: Why Hitler hated modernism

- Published

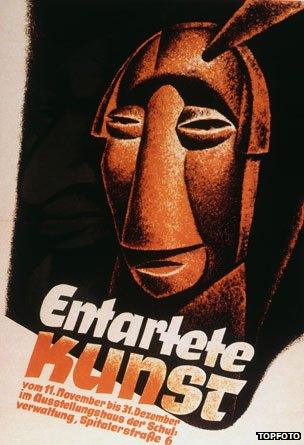

This week it was revealed that a huge stash of modern art had been found in a flat in Munich. Many of the paintings were considered "degenerate" by the Nazis, who staged an exhibition especially to ridicule them. Why did Hitler hate abstract art so much?

In July 1937, four years after it came to power, the Nazi party put on two art exhibitions in Munich.

The Great German Art Exhibition was designed to show works that Hitler approved of - depicting statuesque blonde nudes along with idealised soldiers and landscapes.

The second exhibition, just down the road, showed the other side of German art - modern, abstract, non-representational - or as the Nazis saw it, "degenerate".

The Degenerate Art Exhibition included works by some of the great international names - Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka and Wassily Kandinsky - along with famous German artists of the time such Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde and Georg Grosz.

The exhibition handbook explained that the aim of the show was to "reveal the philosophical, political, racial and moral goals and intentions behind this movement, and the driving forces of corruption which follow them".

Works were included "if they were abstract or expressionistic, but also in certain cases if the work was by a Jewish artist," says Jonathan Petropoulos, professor of European History at Claremont McKenna College and author of several books on art and politics in the Third Reich.

He says the exhibition was laid out with the deliberate intention of encouraging a negative reaction. "The pictures were hung askew, there was graffiti on the walls, which insulted the art and the artists, and made claims that made this art seem outlandish, ridiculous."

British artist Robert Medley went to see the show. "It was enormously crowded and all the pictures hung like some kind of provincial auction room where the things had been simply slapped up on the wall regardless to create the effect that this was worthless stuff," he says.

Hitler had been an artist before he was a politician - but the realistic paintings of buildings and landscapes that he preferred had been dismissed by the art establishment in favour of abstract and modern styles.

Farmstead, painted by Hitler in 1914

So the Degenerate Art Exhibition was his moment to get his revenge. He had made a speech about it that summer, saying "works of art which cannot be understood in themselves but need some pretentious instruction book to justify their existence will never again find their way to the German people".

The Nazis claimed that degenerate art was the product of Jews and Bolsheviks, although only six of the 112 artists featured in the exhibition were actually Jewish.

The art was divided into different rooms by category - art that was blasphemous, art by Jewish or communist artists, art that criticised German soldiers, art that offended the honour of German women.

One room featured entirely abstract paintings, and was labelled "the insanity room".

"In the paintings and drawings of this chamber of horrors there is no telling what was in the sick brains of those who wielded the brush or the pencil," reads the entry in the exhibition handbook.

The idea of the exhibition was not just to mock modern art, but to encourage the viewers to see it as a symptom of an evil plot against the German people.

The curators went to some lengths to get the message across, hiring actors to mingle with the crowds and criticise the exhibits.

The Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich attracted more than a million visitors - three times more than the officially sanctioned Great German Art Exhibition.

Some realised it could be their last chance to see this kind of art in Germany, while others endorsed Hitler's views. Many people also came because of the air of scandal around the show - and it wasn't just Nazi sympathisers who found the art off-putting.

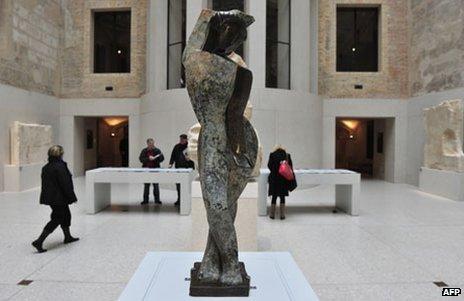

Female Dancer by Marg Moll was in the Degenerate Art Exhibition

Fritz Lustig was a young Jewish apprentice who went along to see the works of art. He says "they didn't seem to mean very much - if they were portraits they seemed to distort the faces... if they were things, they seemed to be quite different from what the things really looked like - I mean the word degenerate seemed to me to apply".

The exhibition went on tour all over Germany, where it was seen by a million more people.

Some of the art was later burned by the Nazis, and for many of the artists this was only the beginning of very hard times ahead.

But Petropoulos says that for some, being banned by the Nazis turned out to have a positive side.

Max Beckmann triptych being hung at London's New Burlington Galleries, July 1938

"This artwork became more attractive abroad, or certainly in anti-Nazi circles it gained values because the Nazis opposed it, and I think that over the longer run it was good for modern art to be viewed as something that the Nazis detested and hated."

Some of the artists featured in the exhibition are now considered among the greats of modern art.

Lustig, who later fled the Nazis to settle in England, now enjoys the art that he once thought was degenerate.

"Well, I have grown up since that - I was pretty young and I hadn't seen all that much art - I've changed my mind since then," he says.

"I can appreciate modern art much better now than I did then. It's not meant to be beautiful is it?"

Lucy Burns was reporting for Witness - which airs weekdays on BBC World Service radio. You can hear her report on degenerate art here.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external