Is there an 'angst canon' of books that teenagers read?

- Published

It's 100 years since the birth of Albert Camus. His book The Outsider is one of a select set of works that generations of disaffected teenagers have turned to as a rite of passage.

The 1942 novel, also known as The Stranger, is about a French Algerian's seemingly irrational murder of an Arab and his subsequent indifference to his own execution. Central character Meursault is a man alienated from the society in which he lives.

There's The Catcher in the Rye by JD Salinger. Central character Holden is alienated from the society in which he lives. George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four is a critique of totalitarian societies, but it's also about Winston Smith and his alienation from the society in which he lives.

Aldous Huxley's Brave New World provides a dystopian vision of the world - through the eyes of a man alienated from the society in which he lives. Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar has a female protagonist whose mental illness is partly because of her alienation from a society which has fixed expectations of women.

Then there's Joseph Heller's Catch-22 where central character Yossarian is rather alienated. And Franz Kafka's The Trial where… You get the picture.

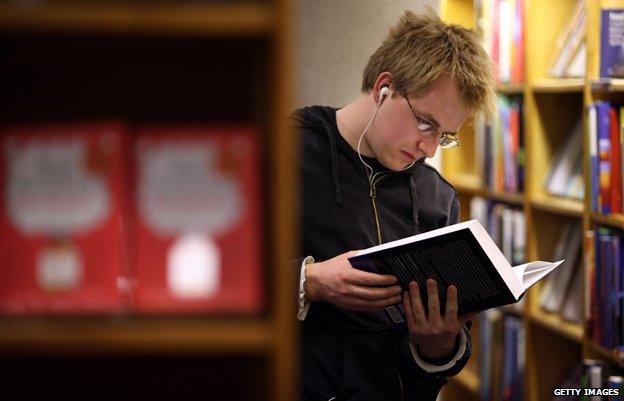

These books have formed a kind of canon of disaffected literature for disaffected teenagers. At the age of 17 and 18, readers are often searching for something with a bit of existential angst. And nothing taps into teenage angst quite like the idea of exceptionalism.

The books in "the canon" can provide a feeling of uniqueness - a clandestine understanding of the world that nobody else quite gets.

"'I can see through this, and Kafka can, but you can't'," says Guardian literary critic Nicholas Lezard of the feeling. "'Me and Kafka, we're buddies.'"

A book like Catch-22 provides a prism for teenage readers, says Prof John Sutherland, an English literature professor at University College London.

"It had sort of this ironic view of the adult world, where you're always trapped. [These books are] intellectual breakthrough stuff, a way of breaking out, a rite of passage."

As well as looking for echoes of their disaffection, teenagers are also often attempting to look, well, a bit cool. The books are like a badge of honour. An actual badge, in Lezard's case.

"I found a badge for sale that just had the word 'Outsider' on it," he says. "I wore that on my school blazer for a bit."

The book itself might be placed conspicuously on show, with the titles poking out of school blazer pockets and tops of satchels. "[They're] what you might call 'accessory books'," says Sutherland.

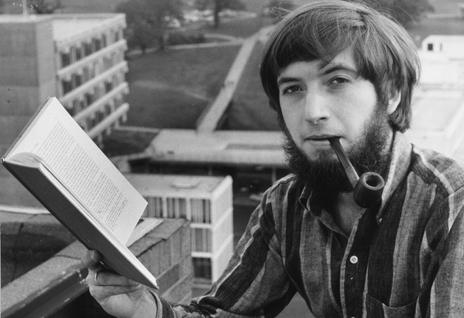

"The book was, as it were, to make a statement. It was particularly pronounced in 1960s, 70s and 80s adolescence. People used to sit around in coffee shops holding a copy of whatever the latest Samuel Beckett was and probably couldn't answer how many Ts there are in Beckett."

Any teenager seen reading the book on public transport is sending out a message.

"You know that if you sit on the Tube reading that [type of book], people will know you're an angst-ridden teenager," says historian Lisa Jardine, who has researched the reading preferences of men and women.

Some may even detect a note of pretentiousness although most teenagers stop short of sporting a beret and pipe and disdainfully peering over a French-language copy of L'Etranger [The Outsider].

But calling the majority of teenagers pretentious is too harsh, says Jardine.

"I don't like that word. I would call it 'statement reading'," she says. "They're exploring them, and they're struggling with them, and therefore it's more about statement than showing off. You swap [the fact] that you've read these books and then you know you've got a kindred spirit."

Even if there is some posturing, it's not unhealthy, says Lezard, as it's partly about raising your game into adulthood - and some of the ideas do filter in. "So I don't regret any of this," he says. "Perhaps the badge."

But the canon of teenage angst books is not the same for both sexes.

"There's an absolutely dramatic difference between what girls and boys read at puberty," says Jardine.

"Boys read angst books, so they read Catcher in the Rye, L'Etranger and books like that. Girls read expanding emotion and sensibility books. Jane Eyre, [Dodie Smith's] I Capture the Castle, the Brontes… books about difficult relationships.

"It was absolutely staggering how little teenage angst books came up on the women's list."

Men also tend to cling on to their teenage favourites later into life more than women, Jardine's research showed.

But does the canon stay the same? And is there always a group of angsty teenagers to read it?

"Nineteen Eighty-Four makes you re-evaluate society," says 17-year-old Enosh Ghimire, from Ealing, west London. "It's a common theme in many of the books - criticising society or evaluating what society is."

The Hunger Games: From bestseller to blockbuster

The canon itself isn't stable. New books may be added, others fall by the wayside. A good movie adaptation can be an obstacle.

Trainspotting, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest - those reaching adolescence after these films came out had to be extra committed to read the books after watching them - or disciplined enough to read them first.

Ghimire says he and many of his friends enjoy reading Game of Thrones and that many are reading the Hunger Games, both of which have popular TV or movie franchises to accompany them.

Laura Hampson, 18, from Liverpool, says her friends don't read that much but "they've read The Perks of Being a Wallfower recently because of the film". Hampson is a fan of contemporary John Green titles Looking for Alaska and An Abundance of Katherines.

But she says her favourite book is David Nicholls's popular book One Day, pointing to its unusual time structure and relatable characters.

"It didn't make out either character was without fault," she adds. "With some romance books the other character can sometimes be described as this perfect person, which most people can't relate to."

Another obstacle to the cultish or cool feel of books in the canon is the way many of them have been absorbed into English literature syllabuses on both sides of the Atlantic over the past 30 years.

Fashions in reading can change

Ghimire studies both Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four as part of his course, admitting that they're not books he'd normally read.

"School opens [them] up," he says. "I wouldn't have known about Brave New World if it wasn't for school. School made me aware that there are other books outside of what I would normally read."

But news and current affairs makes some of the books resonate further, he says, citing the Edward Snowden spying affair as making Nineteen Eighty-Four really click.

"And Brave New World is going to be relevant for a long time because of technological advances," Ghimire says.

And it's only with a sense of irony, or perhaps disappointment, that teenagers realise their mum's favourite book was also Nineteen Eighty-Four and their dad's was Catch-22.

"The feeling of being awkward and unhappy at school is in fact perennial," says Sutherland.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external