Pushinka: A Cold War puppy the Kennedys loved

- Published

During the Cold War, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and US President John F Kennedy wrote to each other regularly. Despite the hostility between their countries, the two men also exchanged presents. One was a dog called Pushinka, whose mother was one of the first dogs to fly into space and return alive.

"My mother told a funny story," says Caroline Kennedy, who is now the US ambassador to Japan, but was once - a little over 50 years ago - a toddler growing up in the White House.

"She was sitting next to Khrushchev at a state dinner in Vienna. She ran out of things to talk about, so she asked about the dog, Strelka, that the Russians had shot into space. During the conversation, my mother asked about Strelka's puppies.

"A few months later, a puppy arrived and my father had no idea where the dog came from and couldn't believe my mother had done that."

The puppy was Strelka's daughter, Pushinka, listed on her official registration certificate as a "non-breed" or mongrel.

"Pushinka was cute and fluffy," says Ambassador Kennedy - in fact the Russian name translates as Fluffy.

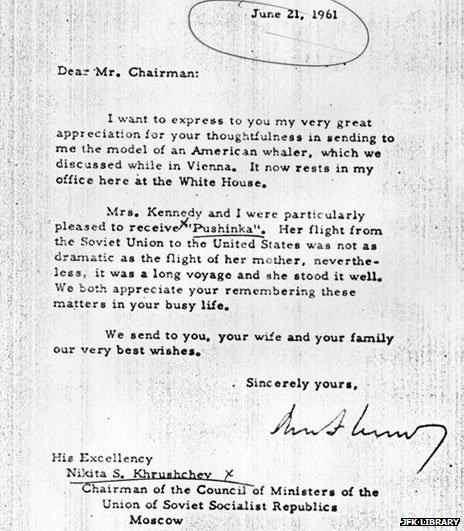

Kennedy's letter to Khrushchev thanking him for the gift is one of many letters exchanged between the leaders.

"It's very interesting to see the warmth in the conversations - these are two guys who know they are the two most powerful men in the world," says historian Martin Sandler, who has just published a collection of Kennedy's letters.

But at the same time, he says, "one-upmanship goes on throughout the whole correspondence".

Kennedy "was absolutely apoplectic, as were most Americans, when the Sputnik went up," he says referring to the world's first satellite, launched by the Soviet Union.

The fact that Pushinka's mother, Strelka, and another dog Belka, were the first living creatures to orbit the earth and survive also highlighted the fact that Moscow was ahead in the space race.

Kennedy responded by pledging to put a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s.

Archive film of Pushinka on the lawn at the White House

Pushinka soon settled in to the White House according to Traphes Bryant, one of the staff who looked after her.

"Pushinka could climb a ladder up to Caroline's playhouse. She'd get up to the top of this little platform and then she would slide down the metal chute," Bryant told the John F Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, external.

"President Kennedy asked me how I taught [her]... I told President Kennedy I moved a peanut up step by step. He laughed when I showed him the pictures.

"Caroline once told me, 'Bryant, don't feed Pushinka peanuts. The vet said it wasn't good for Pushinka'. I quit the peanut feeding."

One of the Kennedys' other dogs, Charlie, took a shine to Pushinka.

"I was so excited when it had puppies with my Welsh terrier because I got to name the puppies - Blackie, White Tips , Butterfly, and one more," says Ambassador Kennedy - the last one was called Streaker.

Blackie and White Tips (centre) with the Kennedy family, Caroline is stroking Charlie on the right

The president called them "the pupniks" and Bryant says he liked to ask questions about them. "How long would the pups keep their eyes closed? When they would be on solid food? How many days? When could they walk? When could they go out on the lawn to play? Would they have short or long hair?"

Once the president asked Bryant to take Pushinka and the puppies to the family home on Cape Cod, as a surprise for the children.

"Mrs Kennedy told me… that would be the only time that the children would be able to enjoy the pups… the four pups were given away before they returned to the White House. Pushinka missed them," he said.

Approximately 5,000 members of the public wrote to the White House asking if they could have a puppy. As a result, Butterfly and Streaker were given to children in the Midwest while White Tips and Blackie went to friends of the family.

Pushinka also began to spend less time playing with the family.

"Apparently Pushinka, who had been raised in a science lab, was a little high strung, as she became a little nippy. I didn't see much of her after that," says Ambassador Kennedy.

But the relationship between Khrushchev and Kennedy continued to develop with regular communication - often carried out in secret.

Nikita Khrushchev's son, Sergei Khrushchev, who lives in the US, says his father "thought it would be pleasant for the family and good for politics".

"My father had a character that wanted to build bridges between people… they communicated regularly as both wanted to reduce tension and stop nuclear testing," he says.

Nikita Khrushchev and John F Kennedy in Vienna, June 1961

Sergei Khrushchev rejects media reports that his father regarded Kennedy as weak, or inexperienced. In fact, he says, his father respected Kennedy for never asking to break their talks at a summit in Vienna in June 1961 to consult his advisers.

"My father liked Kennedy's understanding of foreign policy - creating it himself. It was not the State Department but the president himself who would dictate the politics."

In October 1962, just 16 months after the Vienna summit - and the delivery of Pushinka shortly afterwards - the US and the Soviet Union found themselves on the brink of nuclear war.

The US had photographs that proved Russian nuclear missiles were stationed in Cuba - the weapons were capable of striking Washington and other American cities.

In the end Khrushchev agreed to dismantle the missiles and ship them back to the Soviet Union.

In return Kennedy promised the US would not invade Cuba and would lift the naval blockade imposed on the island.

"After the Cuban missile crisis the two men both said they were very different," says Sergei Khrushchev, describing their new attitude as: "We defended our treasures but we have one thing in common - we want to preserve peace and work for this together."

Sandler also thinks that communication between the two leaders, including gifts such as the dog, had a huge impact.

"In the end," he says, "that's what saved the world from nuclear destruction."

Martin Sandler spoke to Newshour on the BBC World Service.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

On a tablet? Read 10 of the best Magazine stories from 2013 here