What happened in the rest of the world in 1066?

- Published

British people tend to see the world through key dates - 1066, 1815, 1914, 1945 etc. But what was happening in other parts of the world in those fateful years, asks Dr Michael Scott.

Last year I was watching the build-up to the London Olympics opening ceremony when a commentator quipped: "This will be a date you will never forget."

It got me thinking. There are, of course, dates in each of our lives we will always remember. But there are also dates like that in history, dates that have been drummed into our heads through countless school history lessons, textbooks and commemorations: 1066, 1815, 1914.

Crucial dates on which things happened in a particular place, which defined eras and in some cases, still define Britons today.

But that commentator's line also got me thinking. What else was going on around the world at the same time as the Olympics?

And the same question could be asked of crucial dates in history - famous because of an event happening normally in just one part of the world. In 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, may have been invading England, but what was happening in the rest of Europe, Central Asia, China, Africa, the New World?

The problem with learning history by key dates and moments is that it gives us a spotlit view of the past - bright stars of major events twinkling against a giant - but dark and mysterious - night sky of history. As a result we lose sense of the context of major events, and the ways in which our history - and our world - has been, and still is, connected.

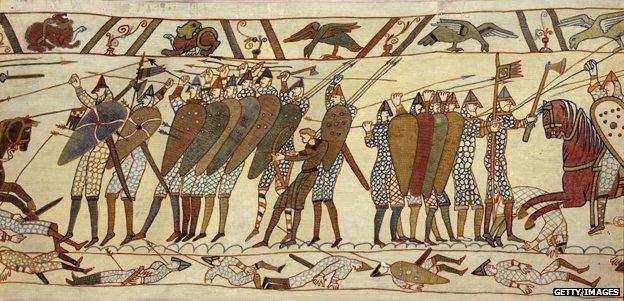

So we set out to find out what was happening elsewhere on 14 October 1066 as the Battle of Hastings was raging.

The Norman knights were also expanding into Sicily and mainland Italy, while the migration of Seljuk Turks from Central Asia was about to threaten the Byzantine Empire, eventually leading to the call for the First Crusade.

But my favourite moment in 1066 is from China, where Sima Guang began writing his monumental history of China, known as the "comprehensive mirror to aid in government".

An exhibition of art from China's Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127) in Taipei

Frances Wood, a former head of the Chinese section at the British Library dug out an early manuscript of this work. Wood explains how this history was supposed to be of use to those in charge - by setting in context the decisions made by China's leaders in centuries past (403-207BC) and by analysing the moral virtues of their actions.

How about 5 November 1605 when Guy Fawkes and his cabal were plotting to blow up Parliament and the king?

Russia was enduring its "time of troubles" - as immortalised in the opera Boris Godunov - and subsequent conflict with the powerful alliance of Poland-Lithuania. Shah Abbas I was building an empire in Persia, while early trading expeditions were attempting colonial settlement in Maine, financed by English Catholics.

The opera Boris Godunov dramatises events from 17th Century Russia

But perhaps most intriguing was Strasbourg, where the first printed newspaper was being published by Johann Carolus, providing regular international news updates for the paper's wealthy readers.

Carolus had earned his living by producing handwritten newsletters, gathering the news from a network of contacts across Europe.

But in 1604 he bought a complete printing shop from the widow of a famous printer and in the summer of 1605, he switched to printing his newspapers, hoping to earn more money by printing a higher circulation for a lower price.

Next year Britain will be marking the centenary of 4 August 1914, when the great European powers went to war following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

But while Europe was focused on war, in Venezuela, Shell struck oil for the first time, igniting not only an era of corrupt parcelling out of land to friends of the man in charge, Juan Vincente Gomez, but also a time in which the position of Venezuela more radically changed from something of a "banana republic" to a serious and powerful player on the world stage - by 1929 Venezuela exported more oil than any other country in the world.

The atmosphere in New York in August 1914 was very different from gloomy London - a vibrant music scene that gave birth to the foxtrot.

The foxtrot came out of the dances of New York's black community, explains Strictly Come Dancing head judge Len Goodman. The most famous dancing couple of the era, Vernon and Irene Castle, were key in putting the foxtrot on the map.

Another date remains shrouded in mystery - that of the birth of Jesus Christ. It appears our ancestors have got the calendar wrong. The historical Jesus was probably born in 4/3BC rather than what was later judged as the turning point of 1BC/1AD.

But as this special child was being born in Bethlehem, not far away in the Roman province of Syria the techniques of glass-blowing were going from strength to strength, as glass became not just a possession of the super-rich, but an affordable luxury for the growing middle classes.

An artefact from the Korean kingdom of Goguryeo

Elsewhere, on the borders of modern-day China and Korea, and we see the emergence of the Goguryeo kingdom, a topic which has recently become politically sensitive as Korea and China both compete to claim it as part of their own cultural heritage. Some claim the very word Korea originates from the term Goguryeo.

The Mayan temple of Chichen Itza, in Mexico

The story of this kingdom sits on the very boundaries of myth and history, as different Korean and Chinese sources speak of the deeds of the kings of Goguryeo, including one fierce leader, King Yuri, whose six sons were to have difficult and disastrous lives. In what would later become Latin America, the Maya culture was flourishing.

What is so often forgotten about the Maya is that they were operating in a jungle environment without beasts of burden and livestock.

That only makes their incredible feats of architecture even more impressive, given the difficulty of clearing space in the jungle and of the need to carry almost all the materials themselves to the sites.

By looking elsewhere we can get a better sense of global history and of the sheer variety inherent in human civilisation, as well as the way in which our world has, and continues to be, connected.

Listen to Spin The Globe on BBC Radio 4 at 16:00 GMT on Tuesday 12 November or listen to it later on the BBC iPlayer

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external