What India's space scientists and street children have in common

- Published

As India launched a mission to Mars this week, I could not help noting some surprising similarities between the ingenuity of the country's space scientists and its street children - many of whom are creative small-scale entrepreneurs.

When you see young children darting between lumbering locomotives to snatch up an empty water bottle or raking through the great mountains of reeking refuse for the plastic bags and broken cardboard boxes they gather together to sell for fractions of a penny, there appears to be an unassailable argument that social welfare should be put before any attempt to reach for the stars.

But I was to discover that neither the plight of Delhi's street children nor the apparent extravagance of India's otherworldly ambitions were quite what they seemed.

The team of Indian scientists designing the delicate instruments made to sniff and probe the Red Planet is based in the Physical Research Laboratory in Ahmedabad, Gujarat's main city.

I had been expecting the kind of shimmering glass monolith you would associate with a Nasa lab or with the headquarters of one of India's world-beating IT companies.

But the cradle of the nation's space research harks back to another, older India.

There is a hand painted No Spitting sign in English and Hindi at the gate. Inside, the slightly shabby 1970s blocks are shaded by gracious tropical trees full of squabbling parakeets.

Yet the scientists who work here confounded the world when India's 2008 lunar probe confirmed the presence of water on the moon - something every previous mission had missed.

"We have had to make a virtue of our limitations," says Professor Jitendra Goswami, the director of the institute and the man behind the discovery.

He is proud that, at £50m ($80m), India's Mars mission is the cheapest in history by a considerable margin. The payload is tiny, just 14.5kg (32lbs). "Small enough to take on as cabin baggage", he jokes.

"Our instruments may cover a very narrow range," he says, serious now. "But they are looking somewhere no-one else had looked - that is how we found water on the moon."

He hopes his mission will help answer a key question - has there ever been life on Mars? - by testing for methane over the entire planet's surface. It will also be looking at how the Martian atmosphere has changed.

I came away impressed by how India's space programme uses its tiny resources to do innovative and original science.

The rocket carrying the Mars Orbiter Spacecraft launched on Tuesday

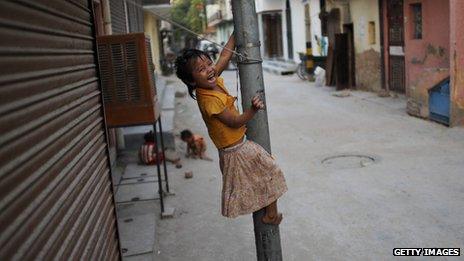

But in some ways what the street children of Delhi do is even more impressive - they find value in something that is regarded as completely worthless by most people, in the city's rubbish.

These are some of the poorest people in what is still a very poor country in the world, yet what strikes you when you meet them is not their desperation and despondency - quite the opposite. Many are energetic and creative entrepreneurs.

My guide was Iqbal, a former street child who had been taken into care by a charity called the Salaam Baalak Trust. Iqbal was abused as a child and ran away to live rough in Delhi when he was just 10. To my surprise he says life was not that hard.

"Food is no problem," Iqbal explains. "Lots of charities give out free food. I would spend the money I earned collecting rubbish playing video games in the backstreet arcades."

In fact, one of the biggest challenges for the Salaam Baalak Trust, and charities like it, is persuading the children to give up life on the streets to go and live in their shelters and homes.

"They get addicted to this sort of life," Gagan Singh, one of the Salaam Baalak trustees tells me, with a sigh of resignation. "They start enjoying the freedom."

Street life may be exciting but it is dangerous. Street children are prey to gangs and paedophiles, many sniff glue and take other drugs. Which is why, Singh tells me, inspiring role models are so important.

In one of the Trust's shelters Iqbal points proudly to a poster with photos of half a dozen former street children brought up by the Trust.

"Amit has just finished an electronic engineering course, Sonia is doing fashion designing, and," he says, clearly impressed, "Niaz is working at Domino's Pizza as a team leader."

In Ahmedabad, Prof Goswami believes the Mars mission should inspire too.

He first became fascinated by space after the launch of Sputnik, the world's first satellite, back in 1957.

"Night after night I lay stretched out on the lawn in my parent's garden in Assam, looking up into the heavens to try and catch a glimpse of Sputnik passing," he says.

He argues that, if the Mars mission is successful, every Indian child, whether in a village in Assam or on the streets of Delhi, can look up into the night sky and, when they catch a glimpse of the red glimmer of Mars, will know their country has been there.

He hopes it will raise the ambitions of the entire nation.

You can listen to Justin Rowlatt's interview with Professor Jitendra Goswami via BBC iPlayer.

From Our Own Correspondent, external: Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external