Minsk's fond memories of Lee Harvey Oswald

- Published

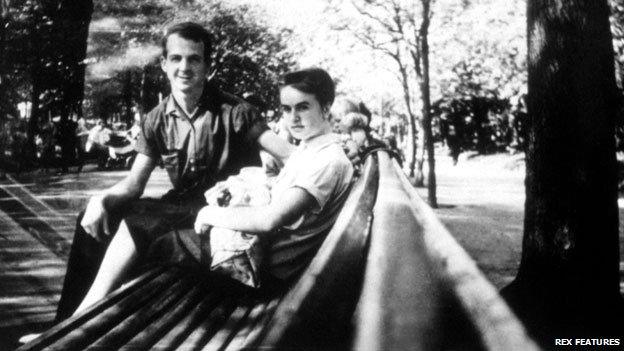

Oswald (centre) with fellow factory workers in Minsk

Mystery and infamy surround Lee Harvey Oswald, the man who shot US President John F Kennedy in Dallas, 50 years ago. So it's odd to visit a city where people remember him clearly and fondly - and refuse to believe he is guilty.

"I just liked the guy," says Ernst Titovets, a medical student who attached himself to Lee Harvey Oswald after the American defector's arrival in Minsk, then the capital of the Soviet republic of Byelorussia, in 1959.

The pair went to dances and concerts together, they both enjoyed practical jokes, and both energetically chased young female students.

Titovets, who spoke good English, was able to play Cupid's helper when Oswald met his future wife, Marina, whom he describes as "attractive in a raw sexual sort of way".

What did he think when he heard Oswald named as the man who had killed Kennedy, and then was himself shot?

A year after leaving Minsk, the world knew the face of Lee Harvey Oswald

"I couldn't believe my ears," says Titovets, now a spry 75-year-old bio researcher. "I deeply believe he was innocent. He was incapable of killing anybody."

Oswald, a 20-year-old former marine, had arrived in the USSR claiming to be a Marxist.

According to Peter Savodnik, whose book The Interloper about Oswald's Minsk years was published earlier this month, he said he had secret details about the US's prized U-2 spy plane.

The KGB however wasn't impressed and initially rejected his application, but on the day his tourist visa expired Oswald slashed one of his wrists. Fearing an international incident if he tried again, the Soviet authorities let him stay.

They sent him to Minsk, a distant provincial capital, which might as well have been Siberia. He was assigned a job at a radio and TV factory, and allocated a one-room apartment in the city centre.

Oswald basked in the attention of being one of Minsk's few foreigners, and its only American. He regularly made social calls to a girls' dormitory, near his flat.

Oswald met Marina in Minsk and June was born in 1962

"He would come without warning and knock at someone's door and say, 'Hello, here I am,'" says Inna Markava, an English-language translator who was a student at the time. "And that's it - spend two or three hours.

"He thought that he was the centre of the group," she says.

"I remember that we were in the room, sitting, and if he thought we had forgotten about him, he would immediately remind everybody, that he was there, that he should not be forgotten."

Oswald was assigned a third-floor apartment on Communist Street, a prestigious city-centre location

The KGB kept close tabs on Oswald, bugging his apartment and drilling a very small hole to record even his most intimate moments.

Titovets says Oswald suspected as much. He remembers one time the two of them looking for listening devices.

After an initial comic mix-up - Titovets thought "bugs" meant insects - they scoured the apartment high and low, finding neither the listening device in the ceiling or the peephole in the wall.

It was only after the collapse of the USSR that he discovered how intense the surveillance had been, and that even the central location of the flat was deliberate.

"He was placed in a carefully thought-out environment, easy to observe his minutest movements," Titovets says.

Inna Markava on the balcony of Oswald's flat, with present occupant Eduard Sagyndykov

At first the KGB thought he might be working for the CIA, and that his stumbling attempts at Russian might be a clever act.

But Norman Mailer, one of the few people to have been allowed to study the KGB files on Oswald, for his 1995 book Oswald's Tale, reveals that instead of hearing Oswald reveal his motives in intimate moments, the KGB tended to get an earful of marital friction.

Oswald: You never do anything!

Wife: Have you ever cleaned up this apartment - just once? I've done it 21 times. You'll do it and then talk about it all day.

Oswald: …You sleep until 10 in the morning and you don't do anything. You could be cleaning up during that time.

Wife: I need my sleep. If you don't like it, you can go to your America… You're always finding fault; nothing's enough, everything's bad.

Oswald: You're ridiculous. Lazy and crude.

Savodnik says Oswald "believed he was a Marxist, a revolutionary" who was "taking part in the cause". But the deeper reason for his defection is "more psychological than ideological," he argues.

"I think he went there because he didn't fit in anywhere else, and he was a desperate and lonely young man, who believed that in Russia he would be rescued."

Before he met Prusakova, he proposed to a young woman called Ella German, and her refusal led to a "growing sense of isolation, detachment, anger and alienation", Savodnik says, which his subsequent marriage failed to reverse.

Titovets noticed that Oswald began to chafe at life in the Soviet Union. There were outbursts.

"Whenever our discussion would concentrate on the differences within the Soviet Union, the ways here, and the ways in the United States, I would say, 'You are unfair to coloured people there,' Titovets remembers.

"And he admits, 'Yes, we are.' But then… he would say, 'You, here, you live like slaves!'"

No-one I spoke to in Minsk believed that Oswald could have assassinated the US president.

This proves nothing. It's human nature to believe only the best about your friends. Still it was somewhat unnerving to hear so many good things about a person whose name is associated with one of the most infamous acts of our era.

I met one of Oswald's former workmates, Vladimir Zhidovich, at a local cafe. He, like everyone else, told me how Oswald was a "good guy" and he couldn't imagine him a murderer.

As we parted, he asked a favour. If I ever go to Texas, he asked, would I lay some flowers on Oswald's grave, from him and the other colleagues at the radio factory?

The request took me aback. I didn't know what to say. On the one hand, this was Oswald we were talking about - a man who may have slain a political leader and irrevocably altered world history. On the other hand, Zhidovich's appeal came from the heart.

I still haven't made up my mind what to do.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external