Does doing yoga make you a Hindu?

- Published

For many people, the main concern in a yoga class is whether they are breathing correctly or their legs are aligned. But for others, there are lingering doubts about whether they should be there at all, or whether they are betraying their religion.

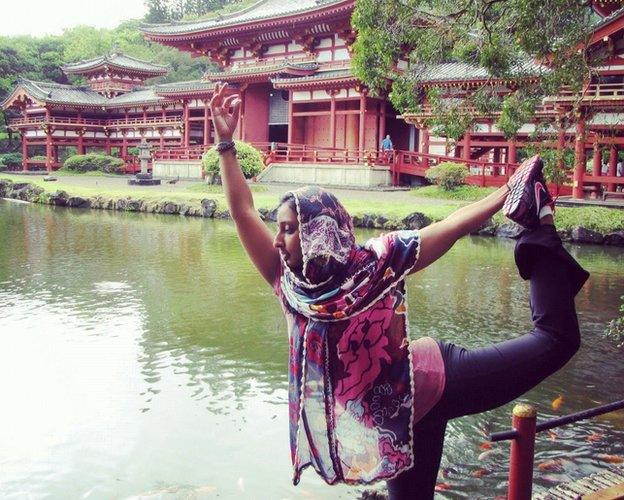

Farida Hamza, a Muslim woman living in the US (pictured above), had been doing yoga for two or three years when she decided she wanted to teach it.

"When I told my family and a few friends, they did not react positively," she recalls. "They were very confused as to why I wanted to do it - that it might be going against Islam."

Their suspicions about yoga are shared by many Muslims, Christians and Jews around the world and relate to yoga's history as an ancient spiritual practice with connections to Hinduism and Buddhism.

Last year, a yoga class was banned from a church hall in the UK. "Yoga is a Hindu spiritual exercise," said the priest, Father John Chandler. "Being a Catholic church we have to promote the gospel, and that's what we use our premises for." Anglican churches in the UK have taken similar decisions at one time or another. In the US, prominent pastors have called yoga "demonic", external.

One answer to the question of whether yoga really is a religious activity will soon be given by the Supreme Court in the country of its birth, India.

Last month, a pro-yoga group petitioned the court to make it a compulsory part of the school syllabus on health grounds - but state schools in India are avowedly secular. The court said it was uncomfortable with the idea, and will gather the views of minority groups in the coming weeks.

So is yoga fundamentally a religious activity?

"Yoga is such a broad term - that's what causes a difficulty," says Rebecca Ffrench, the co-founder YogaLondon - a yoga teacher academy - and the philosophy tutor at the school.

There are different forms of yoga, she says, some of which are more overtly religious than others. Hare Krishna monks, for example, are adherents of bhakti yoga, the yoga of devotion. What most people in the West think of as yoga is properly known as hatha yoga - a path towards enlightenment that focuses on building physical and mental strength.

But what "enlightenment" means also depends on tradition. For some Hindus it is liberation from the cycle of reincarnation, but for many yoga practitioners it is a point where you achieve stillness in your mind, or understand the true nature of the world and your place in it.

Whether that is compatible with Christianity, Islam and other religions is debatable.

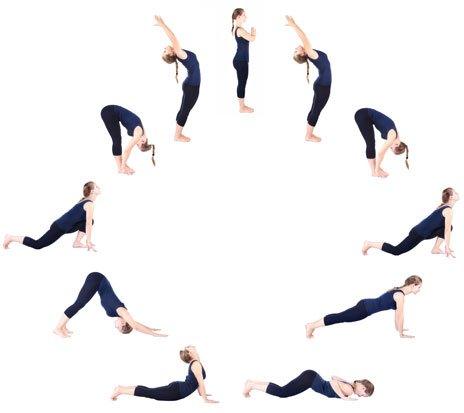

To those in the know, for example, the yogic asanas, or positions, retain elements of their earlier spiritual meanings - the Surya namaskar is a series of positions designed to greet Surya, the Hindu Sun God.

The Surya Namaskar or Sun Salutations

"It's got a trace from history of a religious pathway," says Ffrench. "However, is something religious if you don't have the intention there? If I was to kneel down does that mean I'm praying - or am I just kneeling?"

This was what Farida Hamza anxiously asked herself while she was doing her yoga training, which was held in a Hindu temple.

"I felt very guilty but in the end, I had to trust that Allah understood my intentions," she wrote on her blog, external. "I let them know I did not want to take part in any rituals and they were so respectful of how I felt."

Yoga classes vary. While some feature the chanting of Hindu sutras, others will make vaguer references to a "life force" or "cosmic energy". A session might end with a greeting of "namaste" and a gesture of prayer. There will probably be a moment for meditation, at which point participants may be encouraged to repeat the sacred word "Om", which Buddhists and Hindus regard as a primordial sound which brought the universe into being.

But other classes may make no overt reference to spirituality at all.

That's the way things are in Iran, where yoga is very popular. It has managed to flourish in a country with Sharia law and an Islamist political system, by divesting itself of anything that could be construed as blasphemy. Yoga teachers are careful to always refer to "the sport of yoga" and are accredited by the Yoga Federation, which operates in the same way as a tennis or football organisation.

Classes tend to be slower than in the West with much discussion about the physical benefits of each position. As with other sports, yoga competitions are held, judged by specially invited international yoga teachers.

Similar prohibitions on spiritual yoga exist in Malaysia, where a 2008 fatwa - a religious ruling - resulted in a yoga ban in five states. In the capital Kuala Lumpur, the physical activity is permitted but chanting and meditation are forbidden. Clerics in the world's most populous Islamic nation - Indonesia - make a similar distinction.

Yoga has been repackaged in the US as well.

Children at nine primary schools in Encinitas, California, take part in classes twice a week based on a style of yoga called ashtanga yoga. After some parents complained - US schools, like Indian ones, are secular - the Sanskrit names for the postures were replaced with standard English names and some special child-friendly ones, such as "kangaroo" "surfer" and "washing machine". The lotus position has been rebranded "criss-cross apple sauce", the Surya namaskar has become the "opening sequence" and the organisers insist that it is all just a form of physical exercise.

Students in their yoga class in Encinitas, California

Some parents remained unconvinced though, and a Christian organisation, the National Center for Law & Policy (NCLP) took up their case. In September this year, the San Diego County Superior Court ruled that although yoga's roots are religious, the modified form of the practice is fine to teach in schools.

The NCLP is appealing. Dean Broyles, the organisation's president and chief counsel sees movements like the Surya namaskar, regardless of what they're called, as "deeply symbolic rituals that express and instil religion through repetition".

The reason many people in the West think yoga is non-religious, Broyles says, is that it falls into a theological blind-spot. "Whereas Protestant Christianity focuses on words and beliefs, ashtanga yoga's focus is practice and experience," he says. Religious intentions may not be there to begin with but practising yoga might lead them to develop.

To an extent, this point of view is endorsed by Hindus themselves. The Hindu American Foundation recently ran a campaign called "Take Back Yoga". Sheetal Shah, from the organisation, says someone raised in an "exclusivist" tradition like Islam or Christianity who becomes very interested in yoga may eventually experience some conflict with their religious beliefs.

So, for American Christians who don't like the idea of yoga, there are alternatives, including PraiseMoves.

This exercise regime combines Christian worship with stretching exercises. As the class adopts a posture, they recite a verse from the Bible. In this way, bhujangasana or the cobra pose becomes the vine posture, with a corresponding verse from John 15:5. "I am the vine and you are the branches. If you remain in me and I in you, you will bear much fruit; apart from me you can do nothing."

"The word yoga is a Sanskrit word that means 'union with god' or 'yoke'," says Laurette Willis, the founder of PraiseMoves. "And as a Christian, it's a different yoke - Jesus said: 'My yoke is easy, my burden is light.'"

For someone who has set about drawing people away from yoga, Willis couldn't have a clearer idea of the opposition's terrain. Her mother was a yoga teacher and she started doing it when she was seven, often acting as a demonstration model for the class. She did yoga for 22 years, eventually becoming a teacher herself.

Laurette Willis in the Jars of Clay position "But we have this treasure in earthen vessels, that the excellence of the power may be of God and not of us" (2 Corinthians 4:7)

But she says that on 25 February, 2001, at 10:35 in the morning, while she was working out to a video tape, God gave her the idea for PraiseMoves. She sees it as a process of redeeming or "buying back" yogic postures for God. Just as a musical scale can be used to make good or bad music, so the repertoire of positions in yoga can be put to Christian use.

Despite the similarities between PraiseMoves and a yoga class, Willis says she wants her classes to ruminate, not meditate.

"People leave yoga classes saying 'I feel so good. I feel so tranquil.' Well I believe that tranquillity is not peace - the peace that God gives - but it's almost a numbness.

"You've been told the whole time to 'Empty your mind! Empty your mind!' And what we do instead is fill your mind with the word of God."

But for some Muslims, Christians and Jews, yoga is attractive precisely because it supplies a mysticism they feel is lacking in their own religion.

Estelle Eugene co-runs the Jewish Yoga Network and for 20 years has taught yoga to Jewish and non-Jewish people in London.

"I've found with general Judaism here that it's difficult to find a spiritual side that I relate to," she says. "So the yoga helps me to do that. And it enhances my respect and understanding of Jewish practices that I hadn't fully understood previously."

She says she makes small adjustments to yoga where she feels there is a conflict with Judaism. She never attends or holds a class on the holy day, Saturday, and she prefers classes without the chanting of mantras.

Eugene recently ran a Day of Jewish Yoga, which explored ways of combining yoga with Judaism. One of the sessions combined yoga with practices to help participants reach kavanah, the meditative mind-set seen as an essential for Jewish prayer and rituals.

On her website, a testimonial from Rabbi David Rosen, external, the former chief rabbi of Ireland, says yoga offers "much blessing and enlightenment" and arguably helps "recapture Jewish wisdom and practice which may have been lost".

An Iranian yoga teacher - who wishes to remain anonymous - told the BBC that her religious students sometimes report that they pray with more concentration after practising yoga. "They say when we go to Mecca, we feel we are able to make a deeper pilgrimage because of the yoga," she says. "Our minds and our bodies move closer to our faith."

This is not as contradictory as it might seem, according to Rebecca Ffrench.

"Something that is interesting about yoga is that whilst it is spiritual, it doesn't stipulate a specific religion," she says. "Even in the devotional forms of yoga, it says you can use any object of devotion you like, be it Ganesh, Krishna, Jesus or Allah."

She adds that atheists can also perform yoga - they can fix their attention on the "wonder of the universe" or perhaps the complexity of the DNA helix.

Farida Hamza, meanwhile, is convinced that yoga and Islam are not only compatible, but overlap significantly. The ethical precepts of yoga - captured in the principles of yama and niyama - share many essentials with the five pillars of Islam, she argues.

"Each pillar that we follow in Islam, or the duty that we have to do, is sort of existent in yoga. Simple things like - you give alms to the poor. Well, a yogi is supposed to do service. You have to be honest, you have to be non-violent - all of these are in Islam and in yoga.

Left: sujood (part of Muslim prayer). Right: someone doing yoga

"The way we pray as Muslims, each pose that we do is a yoga pose," she adds. "So Muslims that hate yoga are probably doing yoga without realising it." Muslims even join their middle finger and thumb together during prayer, similar to a yoga mudra, she says, though she doesn't believe Islam came from yoga or was influenced by it.

Born in India but raised in Oman, Hamza sees her path towards yoga as part of a plan drawn up by Allah. "I am grateful for the joy I felt when my hamstrings opened," she says. "And my big toe stretch, or the first time I did a standing bow - it took me two years to do a standing bow.

"But I did it and that is Allah's grace - he blessed me with that."

Yoga and Islam appeared on the BBC World Service. Listen again on iPlayer or get the Heart and Soul podcast.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter , externaland on Facebook, external.