Gettysburg: How Lincoln's speech lived on

- Published

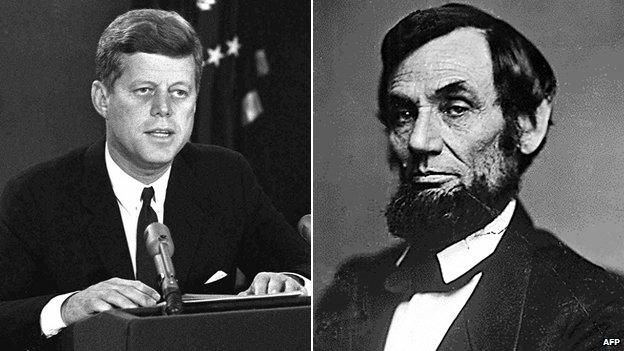

This week saw two landmark anniversaries in American history - 150 years since Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, and 50 years since the assassination of President John F Kennedy.

"Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal."

It is said that it took Lincoln two-and-a-half minutes to deliver the Gettysburg Address, and that it set the tone for a century.

In the three days of fighting at Gettysburg, 51,000 men were killed or injured.

For Lincoln, the war was a test - a test of whether America's great experiment with democracy could survive.

It was still the 1860s - the idea that the people could govern themselves was revolutionary. On that damp, autumnal Pennsylvania field he re-dedicated the American Republic to the ideals on which it was founded.

For a century after the war, though, the post-slavery south enforced strict racial segregation. Black America was locked out of the Gettysburg promise.

This is the century that separates Lincoln from John Kennedy and which binds their fates together in American history - two iconic figures who came to be associated in the American mind with the tragedy of unfulfilled promise.

For the south, the war was not about slavery. It was about states' rights - the right of the individual states to live their own way of life, free from intrusion by the distant federal government in Washington.

It is the fusion of two things that unite Lincoln and Kennedy - the age-old American argument about the proper nature and scale of federal government, and the explosive politics of race.

The Civil War faultline reaches forward into the Kennedy era. In the 1960s, American liberals had come to view southern racial politics as an abomination.

It was apartheid to the New World - an enduring legacy of slavery in the land of the free. John Kennedy began to press for change. The white South revolted.

The South had always solidly voted Democratic. Now, it threatened to defect to the Republicans - the party, ironically, of Abraham Lincoln.

Kennedy was facing re-election a year later and had to win the state of Texas. That is why he went to Dallas.

It is said that as they drove into town from the airport, he told his wife Jackie they were now heading into "nut country". Minutes later he was dead.

Lyndon Johnson was sworn in as president hours after JFK's death

His successor, Lyndon Johnson, used the momentum created by his martyrdom to force through Congress a series of almost revolutionary acts that ended legal segregation and extended voting rights to millions of southern black people for the first time.

In a sense it was the fulfilment of Lincoln's Gettysburg promise.

Is that faultline still active? I went to a Republican Party hustings in Dallas. Every speaker condemned the pernicious expansion of federal power under President Obama as a betrayal of the founding principles of the American Republic.

The meeting began to discuss the merits and demerits of a government ban on texting while driving. Was it consistent with the founding principles? Was it not it a clear and very un-American assault on the liberty of the individual?

"Sure," one man said, "I will support a ban on texting while driving just as long as we also ban brushing your teeth while driving, shaving while driving, reaching in to the back seat to slap your kids while driving."

There followed a bizarre interlude in which speakers sought guidance from the 18th Century framers of the Republic.

What, I found myself wondering, would James Madison and Thomas Jefferson have made of the matter of banning texting while driving?

After the meeting one man, a Tea Party activist, told me that President Obama's attempts at wealth redistribution were only semantically different, as he put it, "to me holding a revolver to your head and telling you to give me your wallet".

It is a graphic image. It means something very specific to a certain kind of listener - Obama cast in the image of a street robber, a mugger.

It is not overtly racist. But it has, for those who want to hear it, a clear racial undercurrent.

The Republicans despised Bill Clinton. But they never challenged his American-ness. Many black Americans believe there is something extra in the Republicans' hatred of Obama.

You are struck, again and again, by the anger that is coursing through much of the Republican Party. It is understandable. Until 2008, they had been in power for the best part of 40 years.

From Richard Nixon in 1968, until George W Bush in 2008 - 40 years in which only two Democrats had made it to the White House, and both were Southern white men. Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton had the mud of the Conservative south reassuringly on their boots.

It seemed, for decades, that conservative America was ascendant, and that liberal America had retreated into a self-destructive, angry counter-culture. Now it is the Republicans - so long the party of government - who are in danger of sliding into that counter-culture status.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external