Why don't French books sell abroad?

- Published

French authors routinely appear in the English-speaking world's lists of the best novels ever - Voltaire, Flaubert, and Proust… sometimes Dumas and Hugo too. But when it comes to post-war literature, it's a different story. Even voracious readers often struggle to name a single French author they have enjoyed.

France once had a great literary culture, and most French people would say it still does. But if so, how come their books don't sell in the English-speaking world?

Is that our fault or theirs?

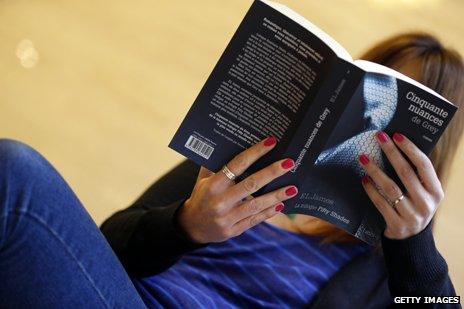

And how come the French themselves read so many books that are translated from English and other languages?

These are provocative questions.

The French take huge pride in their literary tradition - it's been calculated that the country has a staggering 2,000 book prizes. And to accuse their modern-day writers of being elitist, insular or overly intellectual is to invite a torrent of outrage.

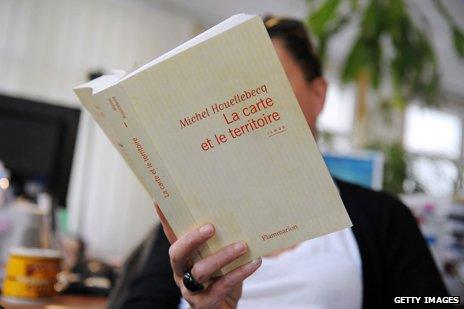

But the fact remains. With the possible exception of Michel Houellebecq, what French novelist has made it into the Anglophone market?

Even the 2008 Nobel literature prize-winner Jean-Marie Le Clezio is virtually unknown in the English-speaking world.

And as for French habits, just look at the popular reads on the Paris metro. My admittedly unscientific survey on Line 1 from La Defense showed a clear four-to-one majority in favour of US and British novels.

For French novelists, the frustration is palpable.

"I am suffering, really suffering, because Anglo-Saxon agents are just ignoring the French book market," Christophe Ono-dit-Biot tells me.

Ono-dit-Biot has just won one of the country's top literary prizes - the Grand Prix du Roman de l'Académie Française - for his novel Plonger (Diving). He now has five books to his name, but without a sniff from the UK or the US.

"Our problem is image. In the US we are famous for French deconstructionism and so on. They think we are too intellectual. They think we are fixated with theory, and that we can't tell stories - but we can!"

It is the same refrain from every author I speak to. All are well-known names in France - Marie Darrieussecq, Nelly Alard, Philippe Labro - but none has been published with any success in the UK or the US.

The French read many more books in translation than the English

Even Marc Levy, whose romantic adventures have sold more than 40 million copies around the world and whose first book If Only It Were True inspired the 2005 Hollywood movie Just Like Heaven, finds the attitude of UK and US publishers deeply irksome.

"The caricature of a British publisher is someone totally convinced that if a book is French then it cannot possibly work in the UK market," he says.

"I often joke that the only way to get published in Britain if you're French is to pretend you're Spanish. If you've been a best-seller in France, it's a sure-fire recipe for not getting a deal in the UK.

"As for US publishers, they're so convinced that with 350 million potential readers and a big stable of American writers, they've got everything covered - every genre, every style. So why bother?"

The costs and difficulty of literary translation are clearly part of the problem. So too is the fact that the Anglophone book market is thriving - so the demand for foreign works is limited.

Some French authors are critical of Anglo-Saxon "complacency".

"Here in France around 45 out of every 100 novels sold is a translation from a foreign language. With you it's something like three out of every hundred," says Darrieussecq, winner of this year's Medicis prize with Il Faut Beaucoup Aimer Les Hommes (You Need to Love Men a Lot)

"But what that shows is that we French are very curious about other people and cultures. You too - you should be curious. You should be more open," she says.

But might there not be another problem - that French books themselves are just not that appealing?

David Rey, who manages the Atout Livre bookshop in eastern Paris, provides an interesting insight.

Unlike most of his peers he knows both the British and French book markets, having lived some years in London. His comparisons are not favourable to the French.

"The books on offer here are very different from in the UK. French books are precious, intellectual - elitist. And too often bookshops are intimidating. Ordinary people are scared of the whole book culture," he says.

The French have preserved a nationwide network of small bookshops, mainly as a result of a system of protection. Books cannot be sold at a discount, which means that "libraires" have kept a near monopoly.

A law passed earlier in the year that prevented online retailers from discounting books led to complaints from Amazon that it was being discriminated against. Meanwhile, the sale of e-books is a fraction of what it is in the US and UK.

But what Rey says about French bookshops is true - many are cramped and colourless. Many (like my local one in the 14th arrondissement) are also very obviously political - which is off-putting.

The books themselves are not made to look appealing. New novels have the same cream cover, with a standardised photo of the author. Design does not seem to be at a premium.

French books are not always made to look appealing

And compared to the UK, there is a glaring lack of offer in certain genres - popular history, popular science, biography, humour, sport.

"Non-fiction books in France are very academic. They are just like university theses. We do not have your knack of popularisation," says Rey.

For the US author of romantic sagas Douglas Kennedy, who lives on-and-off in Paris and is enormously popular in France, French novel-writing has never recovered from the experimentation of the post-war era.

"The reason my books are popular in France is that I combine an accessible style with serious observations about what you might call 'the way we live now'. And there is clearly a huge demand here for what I do," he says.

"It's ironic because it was the French who invented the social novel in the 19th Century. But after World War Two, that tradition disappeared. Instead they developed the nouveau roman - the novel of ideas - which was quite deliberately difficult.

"And now while in the UK or the US it's quite normal to write about the 'state of America' or the 'state of Britain' - no-one is doing that here."

But French writers insist that the sins they are accused of - abstraction, lack of plot and character, a preference for text over story, contempt for the non-literary reader - are a cliche perpetuated by Anglo-Saxons with little knowledge of how things have changed in recent years.

"Personally I am fed up with all the stereotypes," says Darrieussecq. "We're not intellectual. We're not obsessed with words. We write detective stories. We write suspense. We write romance.

"And it's about time you started noticing."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external