The world's most famous missing painting

- Published

It's a century since the man who stole the Mona Lisa was finally caught, two years after vanishing with the masterpiece. Today it's easily the most famous painting in the world, but it took a theft to cement its status.

Vincenzo Peruggia was not the kind of criminal mastermind that makes up the majority of art thieves in Hollywood films. He was not a genius catburglar.

He managed to walk into the Louvre in Paris and walk out with the Leonardo painting after minimal preparation. But his theft created a sensation.

It was a Monday - 21 August 1911 - a day when the museum was closed. Once it became clear the following day that the painting had been stolen, the police got to work, and the museum was shut down for a week amid a scandal.

La Joconde - as the French typically dubbed the Mona Lisa - vanished for more than two years. It was recovered on 10 December 1913, when Peruggia was caught after handing the painting to Alfredo Geri, an antique dealer in Florence.

"This was the single most famous property theft outside war time," says Noah Charney, author of The Thefts of the Mona Lisa: On Stealing the World's Most Famous Painting.

It's easy to assume that the case was big because the Mona Lisa was already "the world's most famous painting". It wasn't. Its status was dramatically enhanced by the affair.

Its theft was the first major property crime that received international media coverage, notes Charney.

The first ingredient in its amplified fame was the slew of coverage during the first two years it was missing, says Financial Times Simon Kuper, who has written on the subject. Before, many people would never have seen it. It was to become a popular icon.

"There she was on newsreels, chocolate boxes, postcards and billboards. Her iconic fame was suddenly transformed into the celebrity of film stars and singers," wrote Darian Leader, author of Stealing the Mona Lisa: What Art Stops Us From Seeing.

Famously, crowds flocked to the Louvre just to see the empty space where the painting had hung. Before, the Louvre had many notable works - including the Venus de Milo, Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People and Gericault's The Raft of the Medusa. After, the Mona Lisa built up a unique kind of fame.

This theft became an affair of state and aroused great passions in France. But once the French newspapers had described the circumstances of the theft, they had nothing more to say about it. Instead they made up stories, trying to say that Leonardo had fallen in love with La Joconde and other bits of similar nonsense, says Jerome Coignard, the author of Une Femme Disparaît.

The police unsuccessfully followed many trails. The poet Guillaume Apollinaire was even jailed for a week and his friend Pablo Picasso was suspected. Both were innocent. The thief's apparently spectacular act had in fact not required any grand or daring plan.

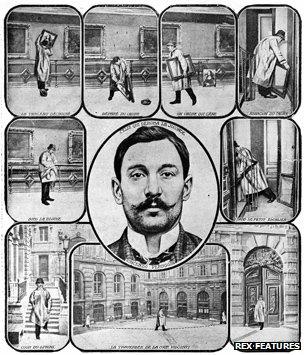

The museum had dubious security and few guards. In fact, remedial work on the poor security had given Peruggia his inspiration. The Italian immigrant worker had been at the Louvre in 1910 and had installed the glass-door that was protecting the masterpiece. He had the white outfit Louvre workers wore and knew how the painting was fixed to its frame.

"These things all fell into place so he saw a window of opportunity," Charney says.

"It did not take huge planning, there was no huge difficulty, he was very lucky," Kuper says. "He was not a master criminal."

After his capture, Peruggia tried to claim patriotic motivation, saying he thought the painting had been stolen from Italy by Napoleon and that his mission was to return it to its source. He was mistaken. The painting had been bought fairly by Francis I in the 16th Century. As an Italian immigrant, Peruggia also argued that he had been subject to racism from French colleagues.

But he had made a list of American art collectors, rather suggesting that he was thinking of selling it, says Charney.

There is another hypothesis that is much more fanciful, says Coignard. In an article entitled "Peruggia's confession", published in 1915 in a French newspaper, it was said Peruggia might have been manipulated by a German man into stealing the painting.

A pictorial representation of the theft shows Peruggia stashing the painting inside his coat

There are different theories about Peruggia's motives. "The truth is we don't have a clue. It still remains a mystery," Coignard says.

Peruggia was not an art connoisseur, not a special kind of thief, says Kuper. He chose the Mona Lisa partly because she was so small, external - just 53cm x 77cm.

"Peruggia had first thought about stealing a painting by Mantegna, another Italian painter, but he chose the Mona Lisa because someone told him it was the Louvre's most spectacular painting," Coignard says. Keeping the Mona Lisa hidden in his small apartment in Paris, he seemed to be ordinary man overwhelmed by his act.

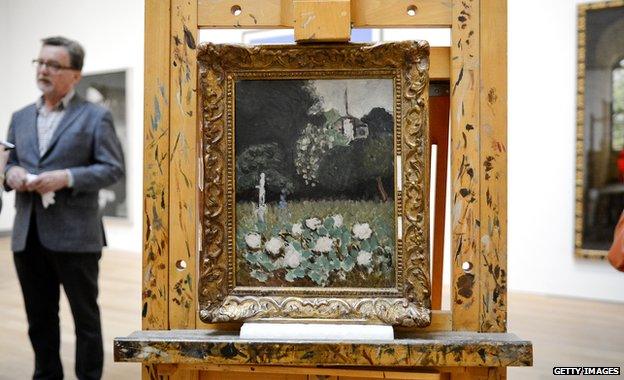

"Today such a theft in the Louvre could never happen," Coignard says. Art thefts do of course still happen. In 2010, five paintings, including a Picasso and a Matisse, external were stolen from the Musee d'Art Moderne in Paris and are still missing.

The robbery of the Mona Lisa also contributed in creating a misconception about art theft that still prevails today, says Charney.

Matisse's Le Jardin was stolen from the Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm in 1987 and recovered in 2012

"People are so used with the romanticised version of what art theft is that they tend not to notice how serious it is. They still think of it as funny and light despite the fact that it is much darker and sinister. The reason is because of film, fiction and the Mona Lisa theft."

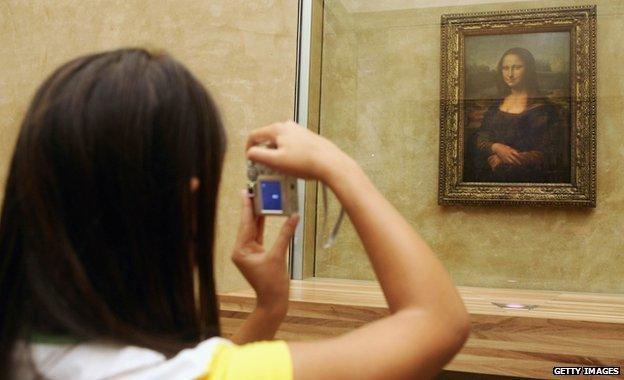

People come from all over the world to see the Mona Lisa but this small and intimate portrait requires calm and some time to be appreciated. This is why few of them really "see" this painting, what is important is to be there and to say you have seen it, says Coignard.

"The Mona Lisa has become one of the wonders of the world. But the idea has replaced its beauty. People are responding to the myth. And the myth was created in part by the theft," Kuper says.

And although a myth came out of it, public opinion rapidly moved on after the thief was caught. "People looked at him as a loveable quirky guy who fell in love with a work of art and did not damage it," says Charney.

Peruggia got off lightly - one year and 15 days in jail, later reduced to seven months and nine days.

"WWI was just beginning. He was quickly forgotten," says Kuper.

"This is a happy story because all is well that ends well. The painting is given back, just before the war starts. It is the last of the happy stories in 30 years of war."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external