Mandela death: How a prisoner became a legend

- Published

As the imprisoned Nelson Mandela became the face of a global campaign against apartheid, within South Africa a ban on his image meant people weren't sure what he looked like - and he became a mythological figure, recalls author William Gumede.

Nelson Mandela was very fond of telling a story of how, in the early 1980s, while at the windswept Robben Island prison where he had been banished for opposing the apartheid regime, he was taken to the mainland in Cape Town for a medical check-up.

His prison warders generously agreed to his request that he be allowed to stroll on the beach for a few minutes. Walking on the beach, Mandela, the world's most famous political prisoner, was anonymous. Having been in jail since the early 1960s, and his pictures banned from being circulated in public or published in the media, very few people knew his appearance.

On the beach that day no-one as much as glanced at him. Later, with a glint in his eye, Mandela said he'd wondered what would have happened had he suddenly shouted: "I am Nelson Mandela."

The images of Mandela imprinted on people's minds were, by then, 20 years old. They were from the last photos to be taken of the defiant activist before he had been carted off to jail in 1962.

In prison he had been allowed only a select few visitors, mostly immediate family. Fellow inmates, who were released earlier, would try to describe him - but it was not quite good enough.

Such was the level of security that by the 1980s no-one appeared to have been able to smuggle out an up-to-date photo of Mandela from Robben Island.

By then, Mandela had become one of the world's most quoted public figures. But in apartheid South Africa his words and teachings, like those of other ANC activists - were banned.

There were injunctions that came with heavy penalties for those who broke them. Carrying the image of Mandela or being overheard saying his name could result in torture and a prison sentence.

Books about Mandela were banned - unless they portrayed him as a terrorist. Media organisations were prevented from reporting on him or using his pictures.

He was not the only prisoner subject to these restrictions, but the way the state tried to erase his image, his words and his name ensured activists revered him even more.

This enforced silence had ultimately done nothing to quell the curiosity of a new emerging generation of anti-apartheid activists in the late 70s and early 80s, in South Africa and overseas.

The long-term imprisonment of most of the ANC's top leaders in the early 1960s, the banning and locking-up of lower level leaders and the brutal campaign of fear pursued by the apartheid government were a crushing blow and threatened the group's very existence.

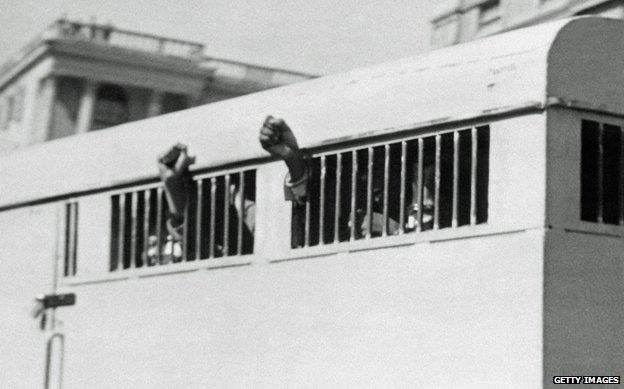

A prison van carrying Mandela and other ANC activists to trial in 1962

Then, in the late 1960s, the ANC's overseas wing decided to change the direction of the anti-apartheid struggle. It launched a global movement as an attempt to give the campaign new momentum, energy and focus.

It fell upon Nelson Mandela to be the face of this new global campaign. His release from custody became the central pillar of the anti-apartheid campaign.

At the time of his arrest on 5 August 1962, Mandela was by no means the ANC's top leader. He was at best below the likes of Walter Sisulu, the ANC general secretary, and Oliver Tambo, its deputy president. Yet this elevation of Mandela to be the face of the ANC also propelled him to the number one spot in the organisation.

The Free Mandela campaign in the West became one of the most effective global media movements. It was also one of the most fashionable causes. World figures such as Bertrand Russell, Simone de Beauvoir and Ilya Ehrenburg put their names to the campaign.

The ANC allowed overseas satellite groups relative freedom to adapt their campaigns for their particular local circumstances, nuances and protest movements.

In the UK, the local anti-apartheid movement hosted an annual Bicycle for Mandela event. In the Netherlands, they issued a Mandela coin in opposition to the Krugerrands. In the US, the committee launched an "Unlock Apartheid's Jails" campaign, under the chairmanship of actor Bill Cosby.

So successful had the global Free Mandela campaign become that in 1978, the prime minister of apartheid South Africa, John Vorster, bemoaned the fact that the world was seeing Mandela as the "real" leader of black South Africa.

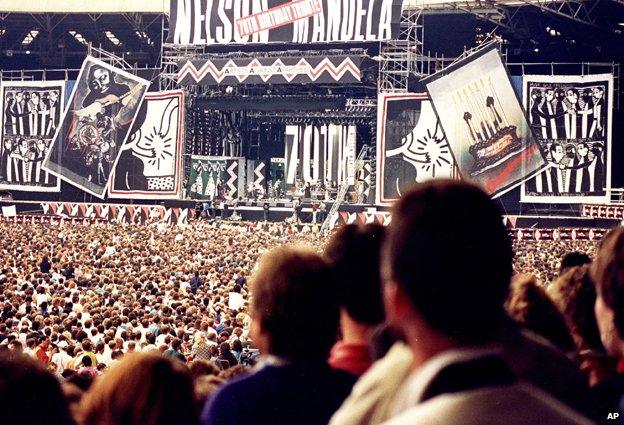

Mandela 70th birthday concert, July 1988, in London

By the mid-80s musicians such as Bruce Springsteen and Miles Davis were sprinkling some stardust on the anti-apartheid movement. The song Free Nelson Mandela became a Top 10 hit in Britain.

The image of Mandela the silenced global statesman was starting to set. Back in South Africa, however, his progression to the top took a different course.

Mandela's long spell of incarceration had led him to deep reflection.

At the start of his prison term on Robben Island, Mandela wrote: "In prison you come face to face with time. There's nothing more terrifying."

Under the tutelage of Walter Sisulu, one of the underrated ANC leaders, Mandela overcame his own "feelings of rage and impotence".

His genius was in his pragmatism - his generosity of spirit. What set him apart from his fellow detainees was that he was wise enough to be influenced by new ideas and in turn was able to soften and broaden the minds of other young radicals, helping him recruit activists from opposing ideologies to the ANC.

Eventually, these new converts, when they were released from Robben Island, spread Mandela's ideas to a wider audience outside.

In the early 80s, to me and my fellow black student activists, Mandela was still a radical, the "Black Pimpernel" who had co-founded Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the ANC.

The rest of the world was becoming acquainted with a more statesmanlike figure. But in the free-speech vacuum of the apartheid state, our Mandela had been freeze-frozen on the day he was arrested on 5 August 1962, for his clandestine attempts to plan sabotage against the state.

It was this Mandela who so appealed to us high school radicals, who came to political awakening in the 80s, leading us to embark on a school boycott between 1984 and 1985.

Scene from a 1985 anti-apartheid riot in Duduza township

Defiance was our core value. We dismissed teachers and parents as too submissive to apartheid authorities, who should be defied in the same way we defied the regime.

As youths we attacked symbols of apartheid and white oppression. We threw stones at the police and army, barricaded roads with burning tyres and "redistributed" to the community the contents of delivery vans of companies perceived to be collaborating with apartheid government.

Senior ANC and anti-apartheid leaders, such as Archbishop Desmond Tutu, publicly disapproved, but as in William Golding's Lord of the Flies, the children would now be in charge, not only of our education, but also our own upbringing.

Our slogans were "No education without liberation", "Victory or death" and "Free Mandela our real leader".

We divided ourselves into cells which met in secret. And in these cells we would talk about Mandela, the ANC and lessons from other people's struggles around the world.

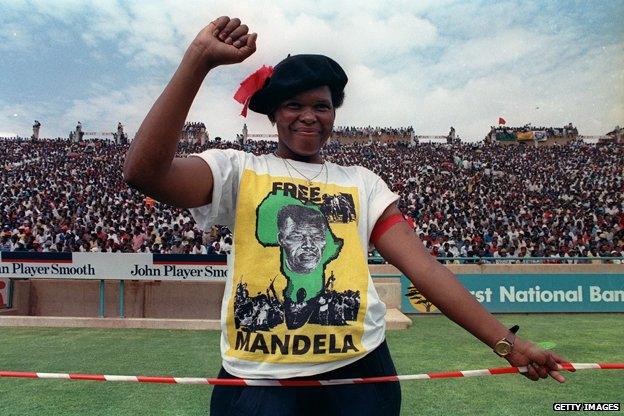

Invoking Mandela's name or his image risked severe retribution. But doing so became an act of defiance for anti-apartheid activists. We wore T-shirts and badges, and carried flags, all with Mandela's face on, knowing we could be arrested and tortured.

The apartheid police had its omnipresent networks of spies or "impipis" in the black community who would rush to inform on anyone who dared mention Mandela's name at church prayer, school or community meeting,

In high school, in 1985, at the height of the student revolt, one of my fellow teen anti-apartheid activists was arrested and given a 30-day jail sentence for drinking out of a mug which had the face of Mandela painted on it.

Another spent three days in jail for writing "Free Mandela" on her school dress.

I was sjambokked - beaten with a traditional South African leather whip which police carried during the apartheid era - kicked and klapped (slapped) by police for drawing a rather crude image of Mandela, next to the words "Liberation Before Education", on my tattered canvas school bag.

An ANC supporter in 1990 - a few years earlier, wearing this T-shirt could have meant prison

But we students weren't the first to get behind the Mandela charge.

In 1980, Percy Qoboza, the editor of the Sunday Post, a black newspaper in Johannesburg, launched a local campaign for the release of Mandela. It led to a wider call which raised Mandela's name again within South Africa after the blanket of silence enforced by the authorities.

Some 86,000 people publicly signed a petition sponsored by the Sunday Post to release Mandela - opening themselves up to prosecution for promoting a banned person.

The Free Nelson Mandela campaign became the glue that brought together many of the disparate grounds whose common goal was to overturn white minority rule, under the name of the United Democratic Front (UDF).

Enuga Sreenivasulu Reddy, the former secretary of the UN Special Committee Against Apartheid, wrote in 1988: "The release of Mandela became an issue uniting the broadest segments of the South African people. All black leaders with any following, as well as several white leaders, expressed support."

The UDF launched a new, more energetic domestic campaign to release Mandela, vowing that unless the Nationalist Party government freed him, there would be no peace in South Africa. Overnight "Release Mandela" committees were set up across the country, in every region, town and township, by UDF activists.

Our curiosity about Mandela remained insatiable.

Comrades who were released from Robben Island, having been in secret meetings where messages from Mandela were clandestinely distributed, were eagerly questioned on the leader's views.

Mandela's cell in Robben Island

Those who were lucky enough to have seen Mandela, even from a distance at Robben Island, let alone to have met or talked to him, were treated like royalty by us youth activists.

Lawyers visiting the island prison were a particularly rich source of information for those hungry for news.

But while beyond the shores of his island prison Mandela had unquestionably become the face of the fight against South Africa's racist government, inside the jail he was locked in a decades-long battle to have his vision for what the organisation stood for, accepted by fellow inmates.

On Robben Island the ANC leadership decided to set up a leadership structure to support activists who could have lost faith in the face of long jail sentences. This was called the "High Order", and consisted of Mandela, Govan Mbeki - father of the future South African President Thabo Mbeki - and two others. Mandela was elected spokesperson.

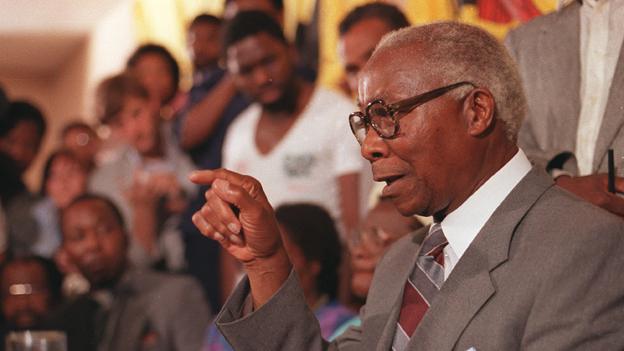

After his release from Robben Island in 1987, Govan Mbeki admitted that "nobody [on the island] could guess" that Mandela would become such an international figure and would rise to such heights.

Mbeki was Mandela's great rival while in prison on the island. Before he was imprisoned, Mbeki was a powerful figure in the ANC and Mandela's senior by a mile.

Govan Mbeki, pictured upon his release in 1987

He later admitted that he "differed very strongly" with Mandela on a great many issues.

Mbeki had challenged Albert Luthuli for the ANC presidency and lost narrowly. On Robben Island Mandela and members of the High Order would secretly circulate their ideas on paper (often toilet paper) to the seven jails of the island prison, or in code in letters to family and to the ANC on the outside. They used every opportunity while doing hard labour, breaking stones on the island's quarry, to clandestinely disseminate their ideas. While doing this, they had to evade the prying eyes of the prison guards and the prison censors.

For three decades in Robben Island there was an epic leadership battle in the ANC for supremacy between the African nationalists, led by Mandela, and the ANC Left, led by African communists such as Mbeki.

Mbeki's group argued that the ANC should seize power through military means, nationalise all industry, pursue Nuremberg-like trials to prosecute apartheid leaders for crimes against humanity, and set up a communist state with the South African Communist Party at its head at the southernmost tip of Africa.

Mandela and his leadership group argued that the ANC was a broad church of all colours, ideologies and classes who were united in their fights against apartheid and racial prejudice. Mandela argued for a negotiated settlement between the apartheid government and the liberation movements, which would cobble together a constitutional, non-racial democracy.

Mbeki feared Mandela was about to sell out, to strike a compromise deal with the Nationalist Party in return for his freedom. He smuggled an SOS to the ANC leadership in exile to express his fears.

Mandela, in turn, smuggled an answer to the exiled leaders, assuring them he was not selling out and that he was acting in the best interests of the ANC members and supporters.

According to Mbeki, who was released ahead of Mandela, it took a long time before fellow Robben Islanders were convinced that Mandela was not selling out.

By the late 80s, my generation, the 1985 generation who were active in the internal struggle, had become suspicious of Mandela, fearing a compromise with the apartheid rulers was about to be agreed.

Even at Mandela's release in February 1990, there was a lingering suspicion among some comrades that he might have turned.

It would immediately be proven wrong. In fact, Mandela had entered Robben Island a good leader, and returned a great leader.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external