How Babycham changed British drinking habits

- Published

It's 60 years since the national launch of Babycham. The sparkling perry was one of the first alcoholic drinks marketed directly to women, and heralded a change in British drinking culture.

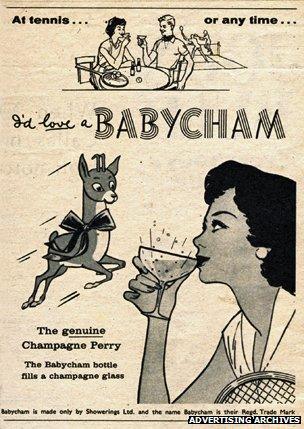

A cinema ad from the early 1960s - a smart young woman straight out of the Rank Charm School is at the country club with her blazered-and-Brylcreem'd companion. "I'd love a Babycham," she announces in a cut-glass accent.

"Genuine champagne perry," says the voiceover (try not to think too closely about that paradoxical statement).

"Babycham was the first drink a woman could order in a bar without feeling a tart or a crone," writes the rock biographer Philip Norman in Babycham Night, his memoir of growing up in the 1950s. Up until that point, choices were limited - port and lemon perhaps, or milk stout for the older lady (for medicinal purposes, of course).

Babycham was a glimpse of a new, more glamorous and aspirational world arising from the ashes of post-WW2 austerity and rationing. "Babycham was posh, it was sophisticated, it was advertised on the telly. It became a symbol," says drinks historian Pete Brown.

Babycham was the brainchild of Francis Showering, a brewer from Shepton Mallet in Somerset. Although perry, or pear cider, had been produced in the west of England for hundreds of years, it was a tricky business - perry pears are difficult to harvest and tend to rot quickly. Showering made the process commercially viable by using ready-made pear juice concentrate. He began entering his "champagne de poire" in agricultural shows where it proved extremely popular. Served in baby bottles, the drink became known as the "baby champ", hence the name.

But Babycham's triumph was as much to do with the brilliance of the marketing as the drink itself. It was the right product for the right moment, according to brand expert Robert Opie. "[The early 50s] were a time of big social change," he says. "Women were getting into that moment, and needed something which was easy and drinkable."

Norman puts it more lyrically in his book: "For dowdy, downtrodden fifties womanhood, it was a heady sip of the high life which most knew only from films and magazines - the world of the cocktail rather than saloon-bar, where people wore evening dress, soft music played and white-coated barmen shook up exotic iced concoctions in silver flasks,"

The animated baby deer logo made the brand instantly recognisable, as did the half-association with champagne. As the ad said, "The Babycham bottle fills a champagne glass!" The company even tried to sue a restaurant critic in the 1960s for claiming that Babycham was trying to pass itself off as champagne.

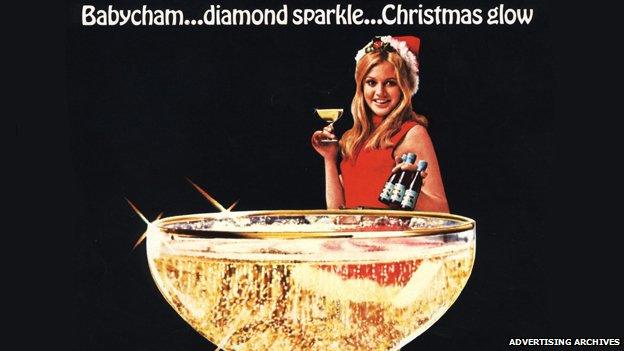

Fast forward to the 1970s, and the TV ads had turned up the glamour element. Raffish leading man (and future Emmerdale star) Patrick Mower is on his yacht somewhere in the Med, blonde companion on his arm, living the life of the international playboy. His drink? Babycham, of course.

But at some point around this time, Babycham failed to leap a crucial generation gap. "Suddenly it became an old-fashioned drink which your parents drank," says Opie.

"It's what my Auntie Pat drank," says Brown. "She never drank apart from Christmas and she never drank anything apart from Babycham." There were undoubtedly a lot of Auntie Pats to keep Babycham afloat, but perception of the brand has never quite emerged from the shadow of "naff". Look at the drink's ad campaigns from the 1980s, which all follow a similar theme - a drinker is at first mocked, and then vindicated, for choosing Babycham. The message seems to be: "Babycham - not as bad as you thought it was."

But what about the drink itself?

There's an affection for it among some wine writers. Helen McGinn is a wine blogger and the author of The Knackered Mother's Wine Club: "I like the lightness of it... it's very light, frothy and easy." Brown agrees: "It's not actually that bad for a sparkling perry. It's a better product than a lot of the pear ciders and alcopops which followed."

But as to whether it'll ever be popular again, opinions are more divided. Opie thinks that brand recognition is not enough ultimately to keep Babycham going: "Some people have immense memories of things like Party Seven. But with so many of these classic brands, we love talking about them but that doesn't mean you can revive the product."

Having said that, sales are still healthy, especially at this time of year, according to Accolade Wines, the Australian firm which now owns Babycham. "It's incredibly seasonal - it's still got a very strong following," says Paul Schaafsma, the company's UK general manager. He adds that it boasts "92% consumer awareness. Most wine brands would be lucky to have 60-70%."

And public taste is difficult to second guess. Campari was considered a moribund brand a few years ago, until it was revived by the fashion for cocktail bitters. "It's one of those retro cool products which people gravitate towards," says Schaafsma. After an unsuccessful attempt to "modernise" Babycham a few years ago, it seems now that those elements which once seemed to date it - the faun, the special glasses - may be what will keep it going, long after the alcopop has been consigned to the bottle bank of history.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external