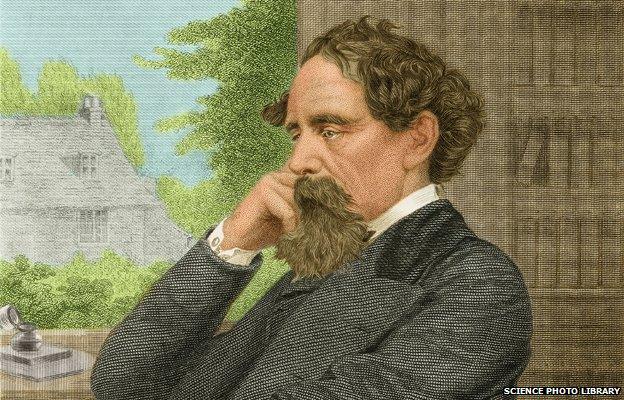

A Point Of View: Why Charles Dickens endures

- Published

Charles Dickens was a close observer of human nature who found endless interest in the theatre of ordinary life, says John Gray.

As Christmas approaches, so Charles Dickens begins to seep once again into TV and theatre schedules. I have my own theory about the reason for his cultural longevity. Listen to this:

"There was a man who, though not more than thirty, had seen the world in divers irreconcilable capacities - had been an officer in a South American regiment among other odd things - but had not achieved much in any way of life, and was in debt, and in hiding. He occupied chambers of the dreariest nature in Lyons Inn; his name, however, was not up on the door, or door-post, but in lieu of it stood the name of a friend who had died in the chambers, and had given him the furniture. The story arose out of the furniture… "

The story Dickens goes on to tell recounts how the failed adventurer finds a heap of old furniture in the cellar of his lodgings. Finding his rooms bare and cheerless, he borrows a writing-table, then a bookcase, then a couch and a rug, and soon has all of the furniture in his chambers. Some years later there is a knock on his door. A tall, red-nosed shabby-genteel man in a threadbare black coat enters the room and, pointing to each item of furniture, mutters: "Mine".

The adventurer offers his visitor a drink, which the visitor gladly accepts. An hour later the visitor leaves, having consumed an entire decanter of gin, falling twice as he stumbles down the stairs. "Whether he was a ghost," Dickens writes, "or a spectral illusion of conscience, or a drunken man who had no business there, or the drunken rightful owner of the furniture, with a transitory gleam of memory; whether he got safe home, or had no home to get to; whether he died of liquor on the way, or lived in liquor ever afterwards; he was heard of no more".

The tale of the failed adventurer and the borrowed furniture comes from one of Dickens's best and least-read books, The Uncommercial Traveller. A series of essays he began in 1860 not long after he had written A Tale of Two Cities and just before he started work on Great Expectations, these short, vivid non-fiction pieces were written at a time when he cast himself as above all a wanderer. "I am both a town traveller and a country traveller," he wrote, "and am always on the road. Figuratively speaking, I travel for the great House of Human Interest Brothers, and have a rather large collection in the fancy goods way." The stories he tells are Dickens's fancy goods, picked up while he tramped the streets.

The Marshalsea prison in London features in Dickens's work

One of the essays, Night Walks, records how he found an answer to insomnia by roaming about London, along the river, past workhouses, prisons, asylums and empty churches, returning only at daybreak. Dickens' solitary walks may have been an escape from his life at the time, which included chronic overwork, illness and death in his family and a secret relationship with a young actress, but the pieces he wrote about his wanderings reveal something enduring about the writer and the man.

As an observer of the human scene Dickens wasn't the cosy sentimentalist to whom we were introduced at school, any more than he was just an angry protestor against Victorian injustice. As he saw it, if I read him right, human life was fickle, erratic and inherently unruly. There was no prospect of remoulding things according to some more exalted plan. Yet this wasn't for Dickens an altogether melancholy thought, for he had a powerful sense of excitement when he contemplated the intractable human world.

Left: Scene from TV adaptation of Bleak House (2011), Right: Oliver Twist (2007)

Dickens didn't seem to share the idea, common among reformers in his day and our own, that there is a more reasonable and better-natured human species hidden away somewhere inside us, waiting to be let out. Listen to his description of the laundrywoman of the chambers where the failed adventurer lodged: "The veritable shining-red-faced shameless laundress… in figure, colour, texture and smell, like the old damp family umbrella: the tip-top complicated abomination of stockings, spirits, bonnet, limpness, looseness and larceny."

Dickens didn't see the laundry-woman as an imperfect specimen of universal humanity, who could become more morally respectable if she was properly instructed. Again, this is his account of what he saw, early one morning in Covent Garden, while having coffee and toast after one of his long night walks: a "man in a high and long snuff-coloured coat, and shoes, and, to the best of my belief, nothing else but a hat, who took out of his hat a large cold meat pudding; a meat pudding so large that it was a very tight fit, and brought the lining of the hat out with it".

Mrs Gamp features in Dickens's 1844 novel Martin Chuzzlewit

Dickens enjoyed human beings as he found them, unregenerate, peculiar and incorrigibly themselves. He has been often criticised because his characters are so grotesquely exaggerated. Miserly Mr Scrooge and the boozy Mrs Gamp, ever-optimistic Mr Micawber and the faded Miss Havisham are theatrical figures, it is said, rather than plausible personalities. But the stagy quality of Dickens' characters is what makes them so humanly believable. Travelling theatres were part of the street life he had known as a child. Showing emotions being fully acted out, these street theatres revealed human beings as they feel themselves to be—creatures ruled by their sensations. It was natural for Dickens to present his characters as figures on a stage. He was himself a travelling performer, acting out his characters in readings of his books in hugely popular tours across Britain and America.

At the same time, the theatrical quality of Dickens' fiction has a deeper source in his view of human life. One of his most striking features - and for me, one of his most attractive - is his lack of interest in grand ideas. It's well known that he was never much engaged with politics, but it's his equivocal attitude to religion that seems to me most telling. Certainly he invoked some of the imagery of Victorian religiosity, particularly the consoling dream of an idyllic after-life where we meet those we have loved and lost. Yet I suspect he may have no more seriously believed we go on to another world where all sorrow is ended than he believed human beings could fashion a world without suffering or injustice. Much as he loved stories with happy endings he preferred human life as he found it, with all its random adventures.

There are many scholarly interpretations of Dickens, but I'm inclined to think this may be the secret of his genius. He was like Shakespeare, who rather than accepting or rejecting religion simply left it on one side. The mediaeval scheme of things was a cosmic hierarchy with God at the top. There are many references to this view of things in Shakespeare, but he doesn't use it is as a frame in which to set the events he portrays. His plays focus on the human realm, and the cosmos is hardly mentioned. Dickens does something similar, I think, but the view of the world he puts on one side is a modern one. More than Christianity, the religion of Victorian times was a belief in human advance - the conviction that freed from ignorance and superstition, humanity could expand its power and be master of its destiny.

Dickens never seems to me to subscribe to this picture of things. For him human life is enacted on a stage, small and brightly lit, and beyond the stage there is only an immense darkness. Some of the dramas conclude happily, as in many of Dickens's novels. Others - like most of those he recounts in The Uncommercial Traveller - come to an end without any definite conclusion. Either way, our human dramas are more comical than they are tragic and they have no meaning beyond themselves.

For Dickens life was a theatre of the absurd, but that was no reason to be down-hearted. For him this world was enough, and he was able to find unending interest and delight in the stories that are played out on the human stage. That's why Dickens is still so close to us, and always will be.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external