The global wine drought that never was

- Published

Recently the world's media reported the alarming news that demand for wine has outstripped supply. Latest figures indicated a shortfall of 300 million cases in 2012, it was claimed... the world was facing the serious prospect of a wine shortage.

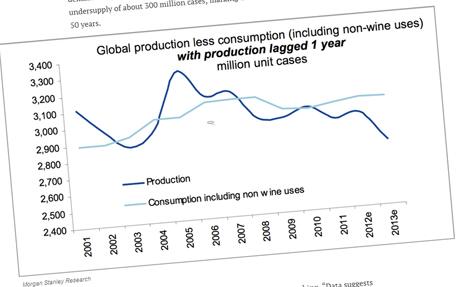

Scary graphs, external were published showing production dropping while consumption increased. The only possibly conclusion - there is not enough wine in the world.

But is it true?

All these news reports were based on a single piece of research carried out by the Australian research division of the investment bank, Morgan Stanley.

This made Reuters finance blogger, Felix Salmon, suspicious - especially when he realised the report was promoting an Australian wine company as a top stock pick to buy.

Morgan Stanley's "scary graph" was widely reported

"What you do in investment banking - you come up with a thesis and argue it as strongly as you can," he says. "The whole idea is that you make a headline, and if you can say a big attention-grabbing headline like 'There's a global wine shortage' then that's going to get you lots of press."

The report was based on industry data from the Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin (OIV), based in France. It represents wine producers in 45 countries and publishes wine production figures three times a year.

But Felix Salmon noticed that the Morgan Stanley graph only used the OIV's data up to 2012, despite the fact data is now available for 2013 production, external - data which showed that wine supplies are bouncing back.

The data had been published by the OIV two days before the Morgan Stanley research hit the headlines.

"After a few years of scarce production we had quite a decent crop," says the OIV's director-general Federico Castellucci.

OIV figures show that in 2013, for the first time in many years, production is going to be much higher than consumption: 281 million hectolitres (Mhl) of wine made, compared with estimated consumption of only 245Mhl.

This would leave an excess of 36Mhl (12.8% of production).

So, Castellucci says there certainly is no wine shortage.

2008: Grapes in a French vineyard, damaged by storms

The data does show that there was a drop in production for the six years prior to 2013. Castellucci attributes that to a series of poor harvests, plus some industry re-structuring. The overall area given over to vineyards has shrunk by 300,000 hectares since 2006.

The Morgan Stanley research said that demand outstripped consumption by 300 million cases in 2012 - but this was taking non-wine products, such as vinegar, into consideration.

Focusing on wine alone, the OIV says that actually more wine was produced than consumed in 2012, by a narrow margin.

Last year's production levels were very low, Castellucci says, but the world was not on the verge of a wine drought, because countries hold wine in reserve. Vinegar and other non-wine products do not need to be made from the current year's wine.

Another test of whether there is a shortage is that you would expect prices to rise.

"This is what indeed happened in 2012," says Castellucci. The cost of bulk wine went up, particularly for European producers.

On the high street, however, the rise in prices was so small that most consumers are unlikely to have noticed.

"If you did a little bit of a check on this you would find that no-one believed there was a global wine shortage," says Salmon.

"If you go down to Spain or France, you would find a lot of vineyards for sale for less than the cost of planting the vines, which is a pretty good evidence that there is no shortage of wine at all.

"The price of wine-producing land is incredibly low."

If wine producers really did anticipate a lasting shortage of wine, vineyards would not be so cheap, he says.

Morgan Stanley was unavailable for comment.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external