A Point of View: A long winter for Christians in the Middle East

- Published

The last decade has been catastrophic for the Middle East's the 14 million Christians, says William Dalrymple.

It won't be much of a Christmas for the Christians of the Middle East. Wherever you go in the region this season, you see the Arab Spring rapidly turning into a Christian winter. Indeed, the entire last decade has been catastrophic for the region's beleaguered 14-million strong Christian minority.

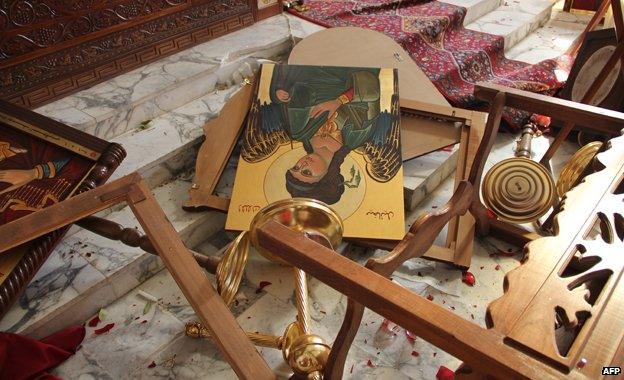

In Egypt, the political upheavals have been accompanied by a series of anti-Coptic riots and intermittent bouts of church burning. On the West Bank and in Gaza, the Christians are emigrating fast as they find themselves caught between Netanyahu's pro-settler government and their increasingly radicalised Sunni Muslim neighbours. Most catastrophically, in Iraq, two-thirds of the Christians have fled the country since the fall of Saddam.

It was Syria that took in many Christians driven out of Iraq a decade ago. Now those Iraqi refugees find themselves facing a second displacement while their Syrian hosts are themselves living in daily fear of having to flee for their lives. Most of the bloodiest killings and counter-killings in Syria have been along Sunni-Alawite faultlines, but there have been some reports of attacks, rape and murder directed at the Christian minority. There are more and more reports of violent al-Qaeda-inspired Salafists taking over the resistance against the Assad regime. The Christian community, which makes up around 10% of the total population, is now frankly terrified. Many are fleeing for Lebanon, Turkey or Jordan. There are tragic reports emerging of the wholesale emigration of the ancient Armenian community of Syria.

For much of this century, and long before the Assads came to power, Syria was a reliable refuge for the Christians of the Middle East. In Assad's Syria, the major Christian feasts are still national holidays. In the Christian Quarter of Old Damascus around Bab Touma, electric-blue neon crosses wink from the domes of the churches, and processions of crucifix-carrying Boy Scouts can be seen squeezing past gaggles of Christian girls in low-cut jeans and tight-fitting T-shirts.

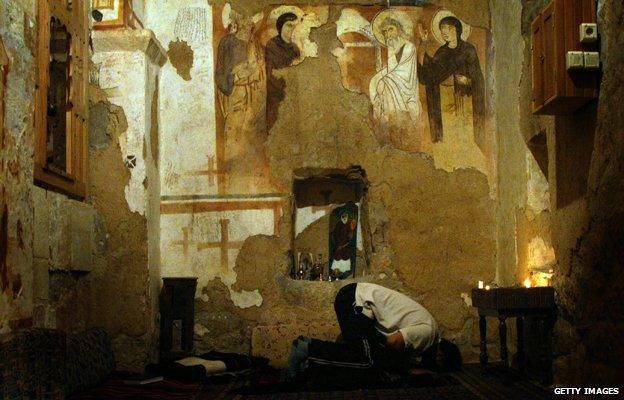

There used to be widespread sharing of sacred space. I have seen Syrian Christians coming to sacrifice sheep at the Muslim shrine of Nebi Uri, while at the nearby Christian convent of Seidnaya, I found the congregation in the church consisted not principally of Christians but instead of heavily bearded Muslim men and their shrouded wives. As the priest circled the altar with his thurible, the men prayed as if in the middle of Friday prayers at a great mosque. Their women, some dressed in full black chador, mouthed prayers from the shadows of the narthex. A few, closely watching the Christian women, went up to the icons and kissed them. They had come, so they told me, to Our Lady of Seidnaya, to ask her for children. Now that precious multi-ethnic and multi-religious patchwork is in danger of being destroyed forever.

I was reminded of this old and often forgotten cohabitation of Islam and Christianity when I visited the old Mughal capital of Fatehpur Sikri, south of my home in Delhi, last week. On the arched gateway of the principal mosque I saw something that startled me when I first saw it 30 years ago. Here was one of the greatest pieces of Muslim architecture, but the calligraphy which lined the inside of the arch leading into the mosque read as follows: "Jesus, Son of Mary (on whom be peace) said: The World is a Bridge, pass over it, but build no houses upon it. He who hopes for a day, may hope for eternity; but the World endures but an hour. Spend it in prayer, for the rest is unseen."

The inscription is at first doubly surprising. Not only is it odd to find an apparently Christian quotation given centre stage in a Muslim monument, but the inscription itself is unfamiliar. It certainly sounds the sort of thing Jesus might have said, but did Jesus really say that the world was like a bridge? And even if he had, why would a Muslim emperor want to place such a phrase on the entrance to the main mosque in his capital city?

The phrase emblazoned over the gateway is, I learnt, one of several hundred sayings and stories of Jesus that fill Arabic and Islamic literature. Some of these derive from the four canonical gospels, others from now-rejected early Christian texts like the Gnostic Gospel of Thomas, others again from the wider oral Christian culture-compost of the Near East - possibly authentic sayings and stories, in other words, which Islam has retained but which Western Christianity has lost.

These sayings of Jesus circulated around the Muslim world from Spain to China, and many are still familiar to educated Muslims today. They fill out and augment the profoundly reverential picture of Christ painted in the Koran where Jesus is called the Messiah, the Messenger, the Prophet, Word and Spirit of God, though - in common with some currents of heterodox Christian thought of the period - his outright divinity is questioned. There are also frequent mentions of his mother Mary who is said to be exalted "above the women of the two worlds (celestial and temporal)" and like Jesus, a "model" for Muslims. Mary is in fact the only woman mentioned by her proper name in the entire Koran, and appears more often in the Koran than she does in the Gospels.

This should not be a surprise. After all, both Islam and Christianity grew out of the same cultural world of the late antique Middle East. Islam accepts much of the Old and New Testaments, and obeys the Mosaic laws about circumcision and ablutions. Indeed the Koran goes as far as calling Christians the "nearest in love" to Muslims, whom it instructs in Surah 29 to "dispute not with the People of the Book [that is, Christians and Jews] save in the most courteous manner… and say, 'We believe in what has been sent down to us and what has been sent down to you; our God and your God is one, and to him we have surrendered'".

In this context, Christmas is perhaps the best moment to remember the long tradition of revering the nativity in the Islamic world. There is a 16th Century manuscript, now in the British Library, which was in all probability painted in Fatehpur Sikri which contains a painting of what - at first - looks like a traditional Christian Nativity scene. In the middle is Mary holding the Christ child, whose arms are wrapped lovingly around his mother's neck. In the foreground, hovering nervously, are the three wise men, ready to offer their gifts. So far, so conventional.

But look a little closer and you begin to notice just how strange the picture is. For the wise men are dressed as Jesuits, Mary is leaning back against the bolster of a musnud (a low Indian throne), and she is attended by Mughal serving girls. Moreover the Christ child and his mother are sitting under a palm tree outside the gateway of a haveli - all strictly in keeping with the convention of Islamic lore which maintains that Jesus was born not in a stable, but in an oasis beneath a palm tree, whose branches bent down so that the Virgin could pluck fruit during her labour.

The miniature illustrating this nativity scene was one of a great number commissioned by the Mughal court under the Emperors Akbar and Jehangir. It is one of the many moments in the history of Islamo-Christian relations that defy the simplistic strictures of Samuel Huntingdon's Clash of Civilisations theory, for both Akbar and his son Jehangir were enthusiastic devotees of both Jesus and his mother Mary, something they did not see as being in the least at variance with their Muslim faith or with ruling one of the most powerful Islamic Empires ever to exist.

As the miniature of the nativity under a palm tree shows, there are certainly major differences between the two faiths - not least the central fact, in mainstream Christianity, of Jesus' divinity. But Christmas - the ultimate celebration of Christ's humanity - is a feast which Muslims and Christians can share together without reservation. At this moment when Christians and Muslims find themselves facing off yet again, there has never been a greater need for both sides to realise what they have in common and, as in this miniature, to gather around the Christ child, to pray for peace.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external