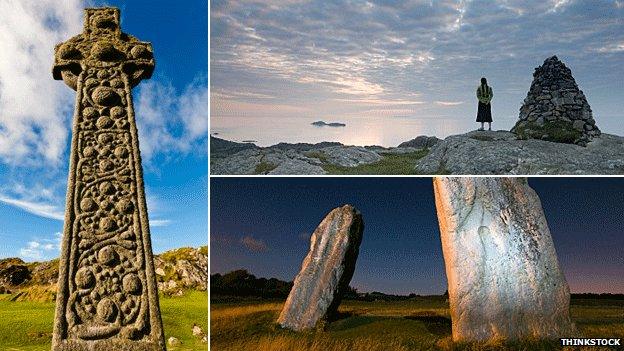

10 extraordinary sacred sites around Britain

- Published

The ancestors of modern Britons saw something special in certain parts of the land and deemed them more sacred than others. Neil Oliver explains why they are so special.

The rich and varied landscape of Britain inspired our ancestors to express their beliefs.

In the flint mines of Norfolk, Stone Age miners carried their religion deep underground and at Flag Fen near Peterborough a vast ancient causeway was built across the fens with sacred objects placed among its timbers.

People are still drawn back to these places today and the belief and ritual that surround them.

So what places did our ancestors deem more sacred than others and why are they so special?

1. Goat's Hole Cave, Paviland, Gower Peninsula

In a sea cave near the base of a cliff on the Gower Peninsula, known locally as Yellow Top (on account of the lichen that grows on its face) a 19th Century archaeologist named William Buckland found an ancient human burial. Noticing at once that the bones were stained with red ochre and the grave also contained items of ivory "jewellery", he assumed it to be the remains of a woman. The find was known thereafter as The Red Lady of Paviland and Victorian minds assumed "she" had been a woman of easy virtue, buried far from polite society in a grave in a cave.

In fact, the Red Lady was a man and recent radiocarbon dates obtained from the remains reveal he lived and died around 33,000 years ago, when the last Ice Age was beginning to exert its grip on northern Europe. He was buried close by the skull of a mammoth and modern archaeologists have imagined he may have died while hunting the beast and his companions saw fit to bury hunter and prey together. Whatever the truth of his life and death, his send-off was marked with great imagination and perhaps even love. I am always touched by evidence that, however much we are separated from our ancestors by great voids of time, in so many ways they were exactly like us. Only their circumstances were different.

2. Creswell Crags/ChurchHole and Robin Hood's Cave

Near Sheffield is a truly awe-inspiring set of caves at the bases of cliffs facing each other across a wide gorge. Archaeological evidence shows they were used for shelter not just by our modern human ancestors but also by our Neanderthal cousins who occupied northern Europe and Britain before the coming of the last Ice Age more than 30,000 years ago. One of the caves, known as Church Hole, has become famous as the location for the most northerly Palaeolithic cave art found so far.

The work of hunters who penetrated the British peninsula of northern Europe as the Ice Age waxed and waned around 13,000 years ago, they are wonders to behold. Animals like bison and ibex, as well as birds like the ibis, and other abstract forms were etched into the limestone walls of the cave by an artist (or artists) living within a few miles of the nose of the glacier itself. It was a world unimaginably different from ours, and much colder and tougher, and yet some of the hunters travelling in pursuit of the reindeer herds upon which their lives depended set aside time to make works of art. In another of the caves, the one known as Robin Hood's Cave, archaeologists found a sliver of horse bone on to which had been etched an exquisite rendering of a horse's head.

The caves, and the gorge itself, clearly mattered to fully modern people - homo sapiens like us - living in that part of the world as much as 13,000 years ago. Woven into their daily lives of hunting and foraging was the need to express some connection they felt to the animals they saw around them, or that their parents and grandparents had told them about.

3. Goldcliff, near Newport in south Wales

On the mudflats of the Severn Estuary, at Goldcliff near Newport in south Wales, the tides are revealing footprints made by Mesolithic hunter-gatherers perhaps 8,000 years ago. Trails of prints, made by men, women and children as well as by animals and birds, were preserved by chance and for millennia beneath layers of mud, silt and peat. Now being exposed once more, thanks to more recent changes in the route of River Severn, they are the most ephemeral traces of humanity imaginable. They are not fossils - the mud is still mud and has not been turned to stone - they are exactly as they would have looked when those long ago hunters made them. However slight they are, each print is nonetheless the proof of a life. While not perhaps "sacred" in the way that a burial chamber might seem, or a stone circle or a church, the sight and feel of those footprints affected me deeply. The fact I could place my own hand into the still-soft print left in silt by a Mesolithic hunter - his partner or his child - made me feel like I was eaves-dropping on a moment in time.

4. Ness of Brodgar, Orkney

Two of the most famous Neolithic stone circles in Britain, Orkney's Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar, are within easy walking distance of each other. Along with the great burial mound of Maes Howe they sit within a natural amphitheatre, a flattened bowl of low-lying land surrounded by hills. The walk between the two circles is across a narrow finger of land between two lochs - Harray and Stenness - and the isthmus itself is dominated by a whaleback shaped ridge that rises several metres above the water level.

Until very recently the ridge was assumed to be natural, a product of geology. But survey and excavation have revealed the whaleback shape is the result of layer upon layer of ancient building work. For centuries during the Neolithic period, around 5,000 years ago, the community expended huge amounts of effort and imagination creating what archaeologists are calling a temple complex. Two huge walls were built across the isthmus, cutting off a huge area of land. Between the walls - several football pitches worth of ground - the people built all manner of stone structures. Most appear like houses to the untrained eye but in fact it seems unlikely they were lived in. Rather they were the setting for rituals and practices associated with some or other ancient religion.

For generation after generation the community built, used and then demolished the structures and over time the layers built up to create the ridge. The religious use of the site seems to have culminated in the demolition of all the separate buildings and then the construction of one, solitary and huge temple. Its walls were several metres thick and supported a roof of great stone slabs. It must have been stunning. Sometime relatively soon after its completion, that building too was demolished and the whole site abandoned forever.

5. Avebury Stone Circle, Wiltshire

The great stone circle of Avebury, perhaps the most impressive monument of its kind anywhere in the world, is a place to strike wonder into every heart and mind. Built during the third millennium BC it is technically a henge monument - a circular area of ground contained by a bank and ditch - containing three stone circles. The great ditch that encircles the whole is itself more than 10m deep and the towering outer bank created from the digging of the ditch would have concealed all activity within from prying eyes. The sheer effort involved in creating the monument - digging the ditch by hand, moving and raising the giant sarsen stones that form the circles - all but beggars belief. That many generations of a community worked so hard for so long to make a reality of their vision makes us shake our heads as we wonder what belief or thought motivated such labour. Even the sober and scientific archaeologists who study the site today will usually admit to being dumbstruck with admiration about such a work of creativity and imagination.

6. West Kennet longbarrow, Wiltshire

One of the most famous early Neolithic tombs, West Kennet long barrow, is a giant of its kind. The mound that encloses the internal, stone-built passage and chambers is well over 100m long and dominates the ridge of high ground upon which it sits.

The passage within is tall enough to let a person stand upright, while the chambers offer more of a crouched space. No more than 40 or so individuals, or the skeletal remains of those individuals, were placed inside the chambers. At some point in ancient times a decision was taken to close the tomb, to put it out of use. This was achieved by hauling into position and then erecting a facade of huge sarsen "blocking stones" that ceremonially barred entrance to the interior. Archaeologists believe tombs like West Kennet were built by the early farmers as part of a means of laying claim to the land.

By being able to point to the tomb and say "my father's bones are in there and those of my father's father and my father's father's father", the community could feel entitled to defend their territory.

7. St Nectan's Glen, Cornwall

Until the making of Sacred Wonders, I had never heard of St Nectan's Glen in Cornwall. It is an astonishingly beautiful, even magical spot, like a fairy glen made real. The glen has been cut by water and erosion during who knows how many millennia. What greets the visitor now is a waterfall that drops around 20m into a natural bowl and then emerges through a circular hole cut by the endless stream. Moss and lichen cloak the sheer sides, along with precariously perched trees, so the whole place has a mysterious, otherworldly atmosphere. Once revered by pre-Roman Celts, who venerated the spirit of the water, and later associated with the 6th Century Saint Nectan, it is still visited today by thousands of people from all over the world. The Arthur myth too has been bolted on and folk thereabouts believe the king and his knights came to the glen to be blessed, before heading out in search of the Holy Grail. Christians, Buddhists, pagans and curious visitors with no religious beliefs of any kind are drawn to the place to this day. Many leave little souvenirs of their visit - single coins wedged into tree trunks, old train tickets from the journey, photos and keepsakes of loved ones.

8. Iona, to the west of Mull, Scotland

St Columba, the man credited with converting the Scottish Gaels to Christianity, fled or was driven out of Ireland in 563 AD. He was likely a high-born son of the O'Neill clan and so able to use his status to befriend the great and the good of western Scotland.

He attended the inauguration of King Aedan mac Gabhrain in 574 and for his efforts was awarded the island of Iona. It was there that he and his followers established a Christian community, which in time became one of the brightest beacons of European Christianity. As well as the faith, Columba and his ilk brought literacy to the tribes. The community on Iona brought stability to much of the west of Scotland and the life of the saint was made immortal by the hand of Adomnan, a later abbot of Iona who wrote, The Life of Saint Columba.

A visit to Iona nowadays is all it takes to make a person understand why the place might have appealed to those early Christians. The island is undoubtedly a place of quiet peace. Whatever the weather the landscape is beautiful and restful to eye and heart both. Religious belief is not required, Iona simply has the magic.

9. Glastonbury Tor, Somerset

Archaeologists and historians are usually people with a scientific approach to their chosen subject. Facts matter and any and all claims and statements ought to be backed up with proof. That being said, who can resist the entertainment provided by a good legend? Glastonbury Tor sits at the heart of one of the best of the bunch. The Tor itself is captivating, rising abruptly from a level plain much given, in ancient times at least, to seasonal inundation by the sea. It was for this reason that adherents of the Arthur legend allowed themselves to see the Tor as Avalon, the island to which the king was carried so that he might recover from wounds suffered while fighting Mordred. Other folk myths have Joseph of Arimathea arrive at Glastonbury with the Holy Grail. His staff is supposed to have taken root as the Glastonbury thorn - that flowers at Christmas time - and the grail itself is said to be buried nearby. In 1191, monks at Glastonbury Abbey claimed to have found the graves of Arthur and his queen Guinevere and the site became a place of pilgrimage for ever after. In short, it is all there. Sacred or not, anyone in search of pleasing legend will find plenty to be going on with at Glastonbury.

10. Canterbury Cathedral, Kent

One of the oldest Christian structures in England - and perhaps the most famous - Canterbury Cathedral is undoubtedly one of Britain's sacred wonders.

The first church there was founded by Saint Augustine, sent by Pope Gregory the Great to convert the Anglo Saxons to Christianity towards the end of the 6th Century. It has been a focal point for Christians ever since but earned a special notoriety following the murder, in 1170, of Archbishop Thomas Becket, apparently on the orders of King Henry II. The grisly act of butchery horrified the Christian world. Soon after there were reports of miracles and Becket's grave became the foremost destination for pilgrims seeking help for whatever ailed them. For those approaching on horseback it was deemed unseemly to travel too quickly.

Rather than gallop towards the shrine, riders adopted the Canterbury Pace, or Canterbury Trot. This has been remembered as "cantering" - a suitably respectful speed.

Sacred Wonders of Britain is broadcast on BBC Two at 20:30 GMT on Monday 30 December, or catch up with iPlayer

On a tablet? Read 10 of the best Magazine stories from 2013.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external