Intermittent fasting: Enduring the hunger pangs

- Published

Scientists in California are conducting a clinical trial to test a diet that may help people lose weight while also boosting resistance to some diseases. One of their guinea pigs was the BBC's Peter Bowes, who reports here on his experience of fasting for five days per month.

It's been tried on mice and now it's being tried on humans - a diet that involves multiple five-day cycles on an extremely low-calorie diet. Each of those five days is tough, but the upside is that for much of the time - about 25 days per month - people eat normally, although not excessively.

The low-calorie period includes small amounts of food to minimise the negative effects of a total fast. Designed by scientists to provide a minimum level of essential vitamins and minerals, the diet consists of:

vegetable-based soups

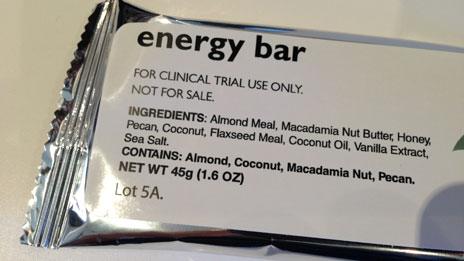

energy bars

energy drinks

dried kale snacks

chamomile tea

These meals are extremely low in calories - about 1,000 on day one and 500 for each of the next four days.

With the exception of water and black coffee, nothing else is consumed.

The limited selection of food (with no choice of flavours) means that everything has to be eaten. It's monotonous... but at least it makes meal planning easy for five days.

"The reason why diets don't work is because they are very complicated and people have an interpretation problem," says Dr Valter Longo, director of the University of Southern California (USC) Longevity Institute.

Spinach soup: Dinner, three nights out of five

"The reason I think these diets work is because you have no interpretation. You either do it or you don't do it. And if you do it you're going to get the effect."

Dr Longo established a company to manufacture the food, based on research in his department at USC. He has shown in mice that restricting calories leads to them living longer with less risk of developing cancer.

The food used during the trial is the result of years of experimenting. The idea is to develop a diet that leads to positive cellular changes of the same kind seen in mice that have been made to fast.

"It turned out to be a low-protein, low-sugar-and-carbohydrate diet, but a high-nourishment diet," explains Longo.

"We wanted it to be all natural. We didn't want to have chemicals in there and did not want to have anything that is associated with problems - diseases. Every component has to be checked and tested. It's no different to a drug."

Longo stresses that the experimental food could not be made in your kitchen.

But it is a big leap from laboratory mice to human beings. Restricting the diets of rodents is easy, but people have minds of their own - and face the culinary temptations of the modern world.

I knew the diet cycles would be difficult.

I love to eat. I enjoy a big, healthy breakfast, exercise a lot and - left to my own devices - snack all day before digging in to a hearty evening meal. At 51, I am in good shape. I weigh 80kg (12 stone 8lbs / 176lbs) but like most middle-aged men, I struggle with belly fat. I have never tried any kind of fasting regime before.

The diet meals were better than I expected - at least initially. I was so hungry I would practically lick the soup bowl and shake the last kale crumb from its bag, to tide me over to the next feeding time.

Note: it is no longer lunch or dinner. It is a feeding opportunity. It is certainly not a social occasion.

Headaches, a typical side effect of fasting, started on Day 2 but they waned within 24 hours, leaving me in a state of heightened alertness. During the day - and especially in the morning - I was more alert and productive. Hunger pangs came and went - it was just a matter of sitting them out. But they did go.

By the evening - especially on Day 5, I was exhausted. Tiredness set in early. But I made it through the five days - for three cycles - without deviating from the regime. I lost an average of 3kg (6.6lbs) during each cycle, but regained the weight afterwards.

All participants keep a diary, noting their body weight, daily temperature reading, meals and mood. The feedback - positive and negative - is vital to the integrity of the study, which is partly designed to establish whether the diet could work in the real world.

For me, and for all but about 5% of the volunteers who have completed all three cycles, the diet was do-able - although opinions vary about the taste of the food.

"It is not an experience for the faint of heart. It was extremely difficult because the little bit of food that you're offered gets very tiresome as time wears on," says Angelica Campos, aged 28.

"I had to isolate myself because my family were constantly offering me food. They thought I was crazy."

She would not want to go through the experience again, but says she would if it were proven to have long-term benefits.

Her boyfriend, Alex de la Cruz, aged 29, says the fasting made him very tired, but when he woke up he was "as alert as could be".

"My overriding memory of the experience is that the food was horrible, but the results were totally positive," he says.

Lead investigator Dr Min Wei says that for some people the diet is a greater wrench than for others, depending on their lifestyle. The absence of carbohydrates and desserts, can hit some people hard, for example, and also the restriction to black coffee alone. "We are fairly strict," he says. "We recommend people stick to the regimen. If people enjoy special coffee - lattes for example - they won't be able to enjoy them."

Data from the volunteers is still being collected and analysed. The early signs are that the diet is safe and could be adopted by most healthy people, providing they are suitably motivated to endure the periods of hunger.

But the full effect can only be measured over the long term. Initial changes in the body may not tell the full story.

"Having dietary factors influence your body sometimes takes years and years," explains Dr Lawrence Piro, a cancer specialist at the Angeles Clinic and Research Institute.

This particular trial now moves into the laboratory. Based on blood tests, has anything changed inside my body to suggest extreme dieting improves my chances of avoiding the diseases of old age?

Tomorrow: My results. See also Wednesday's instalment: Fasting for science.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

On a tablet? Read 10 of the best Magazine stories from 2013 here