La Belle Epoque: Paris 1914

- Published

Georges Boillot nearly reached 100mph in the 1914 Indianapolis 500, a year after Jules Goux won the race

Paris in 1914 was a city giddy with the pace of industrial, scientific and cultural change, but deeply - and as it turned out, rightly - anxious about what the future would hold.

Did Parisians ever have the feeling that they were living through the last days of an era - what we know of now as La Belle Epoque? I doubt it. For one thing, the expression "La Belle Epoque" - which, after all, doesn't mean much more than the good old days - wouldn't even have occurred to them. The phrase doesn't appear until much later in the century, when people who'd lived their gilded youths in the pre-war years started looking back and reminiscing.

But more to the point, on the surface life in Paris… well, it went on. In summer 1913, a party of San Francisco boy scouts passed through the city, and Le Figaro newspaper ran a survey - what had struck them the most?

Apart from the monuments and the gardens, they loved the trees lining the streets, and the general cleanliness. They thought the red trousers worn by soldiers most impressive, but it was odd how many young men wore moustaches and how many women smoked.

They loved the way policemen still wore swords, the dog barbers by the Seine, the glorious outdoor cafes. At the opera, one young American stared at the women "pivoting on their high heels, offering a fine view of their resplendent gowns and jewels". This was Paris on the eve of war. Just doing what it did.

The dome of Galeries Lafayette

On the Boulevard Haussmann, Galeries Lafayette had just unveiled its flagship department store, with a vast domed roof letting in shafts of multi-coloured light, and its teams of assistants - the famous midinettes - selling couture to the aspiring middle classes. This was the time when the flowing lines of the great designer Paul Poiret gave way to the stride-inhibiting hobble skirt.

Interior of the Theatre des Champs Elysees

Further west, the architect Auguste Perret - later celebrated for rebuilding the city of Le Havre after World War Two - had completed his concrete masterpiece, the Theatre des Champs-Elysees - the same theatre where, in May 1913, just a month after its opening, the flamboyant performance of The Rite of Spring by Diaghilev's Ballets Russes had created such a furore.

Looking back from the France of a depressed 2014, it's extraordinary to contemplate the commercial and creative vitality of 100 years ago. The north and western suburbs of Paris were the motor city of the day. There were 600 car manufactories in France and 150 different makes - not just the emerging giants of Peugeot and Renault, but long-forgotten treasures like Berliet and Delaunay-Belleville. Delaunay-Belleville, which operated from what is now the high-immigration suburb of Saint-Denis, made limousines for Tsar Nicholas of Russia. France was the world's biggest exporter of cars, and there was pride, but no great surprise, when the racing driver Jules Goux won the 1913 Indianapolis 500 - in a Peugeot.

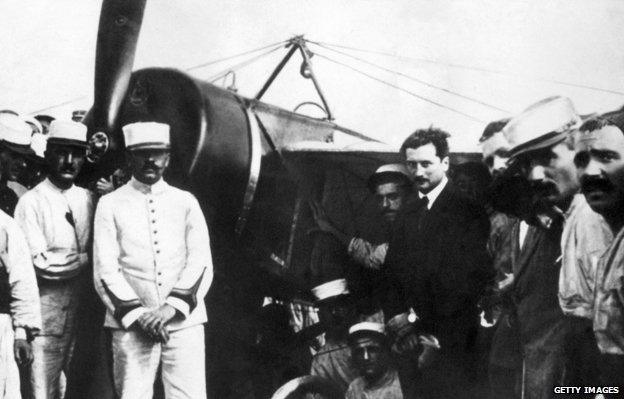

France led the way in the skies. Bleriot crossed the channel in 1908, and in 1913 the sportsman Roland Garros - later (after his death in combat in the last month of the war) to give his name to the tennis stadium in Paris - completed the first ever crossing of the Mediterranean. And in cinema, invented, of course, by the Lumiere brothers two decades before, France vied with the US for first place in number of films produced - more than 1,000 every year, made by names still familiar today like Gaumont and Pathe.

Modernity was the moving spirit. It was the time of the machine. The city's last horse-drawn omnibus made its way from Saint-Sulpice to La Villette in January 1913. From the top of the Eiffel Tower, built 35 years earlier like a symbol of the coming age, a mast had recently been erected, beaming radio waves into the ether. Time and space and movement and energy - they all felt different now.

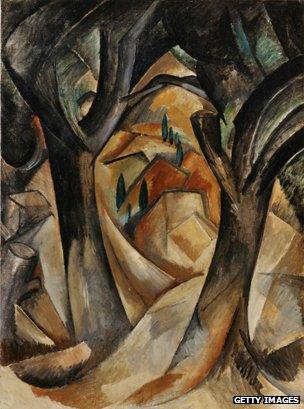

In art, Pablo Picasso and his friend Georges Braque tried (in Paris, of course) to capture this with their new idea - cubism. Instead of painting things as they appeared to a single pair of eyes at a single moment in time, they painted things from a variety of possible viewpoints, creating a shifting world of abstract space.

Arbres a la Estaque (Georges Braque 1908)

In the words of the late art historian Robert Hughes, the cubism of Picasso and Braque, created in the years running up to the war, was every bit as modern - and indeed part of the same destabilising intellectual movement - as the contemporary forays of Einstein into the secrets of relativity.

Destabilising, unsettling, changing, modern, new. I think beneath the veneer of carefree continuation - the eternal gay Paree - there was also at a deeper level a growing sense of anxiety. Most people wouldn't even have been aware of it. Many writers of the time, like Proust and Gide, betray no sense of foreboding. But the speed of change, the rise of technology over craftsmanship, the frenetic search for new modes of artistic expression, as one avant-garde was overtaken by the next (and let's not forget that 1913 was also the year in Paris that Marcel Duchamp presented his first "readymade" - a bicycle wheel on a stool - making the point that anything is art if you say it is), all this must have worked its way into the collective subconscious, creating a feeling that matters were accelerating out of control, that things were conceivable now that would have been inconceivable in their parents' time. Terrible things.

The French writer Charles Peguy is much quoted on this. He said, at just this moment: "The world has changed more in the last 30 years than in all the time since Jesus Christ."

Charles Peguy is forgotten now, outside France. So, too, is another contemporary figure, Jean Jaures. The two men knew each other. At one time they were friends and allies. They died violently, but in very different circumstances, in the summer of 1914. Their stories tell a lot about the anxieties of the age.

Both men were Dreyfusards. That is, at the end of the 1890s they took the side of the Jewish officer Alfred Dreyfus, who'd wrongly been convicted of spying for Germany and whose disgrace and later exoneration divided France into two hostile camps. Peguy and Jaures were also socialists. They looked at the state of France, and behind the surface brilliance - as epitomised in the dashing boulevards of the capital - they saw misery and division.

The public image of Paris was the creation of romantic capitalists. The reality for many was much more wretched. In what is now the 13th arrondissement, below the Austerlitz station, there were entire families living on the street, and decrepit, overcrowded housing with non-existent sanitation. Further out there were bidonvilles - slums made of cardboard and tarpaulin, from where groups of chiffonniers would walk into town in search of junk, which they'd take home and refashion into objects they could sell.

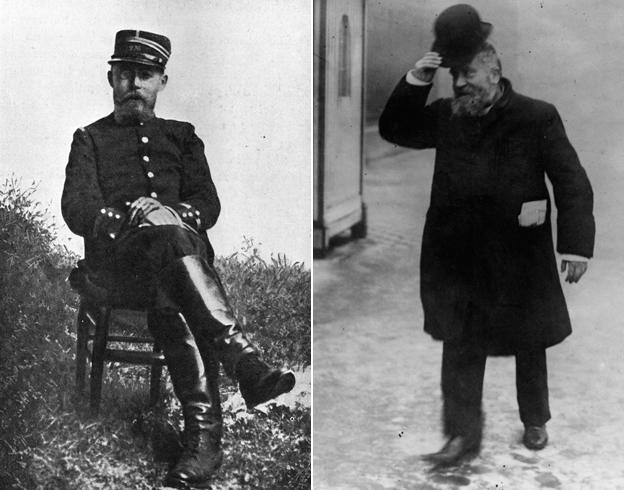

Charles Peguy (left) and Jean Jaures

Jean Jaures became head of the Socialist Party, or to give it its proper name, the French Section of the Workers' International. He himself was not a Marxist, but the party was - believing that the clash of classes would ultimately deliver working people from their yoke.

By 1913 Jaures was a troubled man. Even if others couldn't, he saw the signs of looming war. Two years before, there had been the infamous Agadir incident, when Germany sent a gunboat to Morocco to block French designs. Now the French National Assembly was being asked to vote through a measure that would increase the length of military service from two years to three.

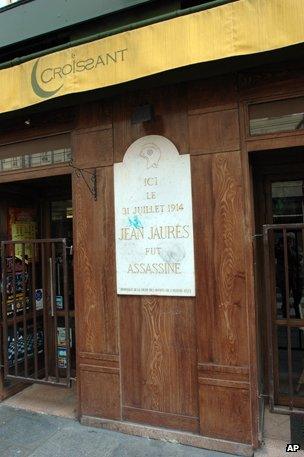

A plaque marks where Jaures was assassinated

Jaures was bitterly opposed. He thought that reinforcing the army would hasten war, not deter it. On 25 May 1913, just before the parliamentary debate, he held a monster meeting in a field in what is now the Paris suburb of Pre Saint-Gervais. More than 100,000 people watched him, in bowler hat and beard, as he railed against the capitalist military machine, and urged the proletariat of all the nations to stand together against war. He lost the vote. Military service was extended, and a year later Europe was preparing to fight.

Jaures flung himself into the task of warding off the inevitable. He activated his contacts with socialists in Germany, desperately trying to arrange an international general strike. If workers refused to fire their guns, he argued, then war would simply stop. On the evening of 31 July he walked from the offices of the newspaper he edited, L'Humanite (still going today), to the Cafe Croissant on rue Montmartre (also still there). As he prepared to eat his dinner, an assassin called Raoul Villain shot him from behind in the head. Jean Jaures, the pacifist, died instantly. Four days later there was war.

Villain, it turned out, was a young man who'd drifted into nationalist circles. He was a member of the League of Friends of Alsace-Lorraine, the eastern provinces that had been seized by Germany in the war of 1870, and he regarded Jean Jaures as a traitor.

Villain wasn't put on trial till the end of the war, and then in the glow of victory he was actually acquitted. But he came to a sticky end. After moving to Ibiza, he was shot on the beach by Republicans at the start of the Spanish Civil War.

Meanwhile Jaures's one-time student, Charles Peguy, was pursuing a different course. He too was incensed by injustice. He hated the anti-Semitic anti-Dreyfus camp, and for years he ran a socialist magazine. But around the year 1908 he had an emotional crisis, and he emerged a Christian and a patriot.

He became the antithesis of Jaures. It would be unfair to say he believed in war. But he certainly believed in the values of France, and he thought that war could be the crucible in which much that was lost could be regained - not just territory, though of course Alsace-Lorraine was also in his thoughts - but spiritually. Peguy was of a generation of middle-class intellectuals in France who were disappointed by the unfulfilled promise of the Republic.

If you look back a little in history, you see how recent it was - on the eve of World War One - that the idea of the Republic had come to be accepted in France. As late as the 1880s, a monarchist restoration was perfectly conceivable. But then prosperity, stability, modernity - all these had brought with them a hope of progress which people associated with the new institutions - and meanwhile the conservative monarchist Catholic right emerged deeply discredited from the Dreyfus affair. All this meant that there was, at the turn of the century, a generalised faith in the Republic, and a hope that it would lead to richer, happier lives.

But by the 1910s much of that promise had vanished. There was material progress, to be sure, with the cars and the planes and the couture. But the French, brought up on ideas and theory, have always yearned for more. So it was that around this time - while some led by Jaures were turning to class politics and faith in revolution - others took refuge in anti-intellectual ideas such as vitality, panache, heroism, sacrifice.

Peguy thought war was necessary to defend the values for which France stood, among which he would count freedom, compassion, Christianity. A lieutenant in the reserve, he was called up at war's outbreak, and on 5 September 1914 he was shot through the head at the start of the battle of the Marne, just east of Paris.

A century has gone by, but one of the bizarre things is how the names of Jaures and Peguy live on in France. Everywhere there are schools, and streets, libraries and sports centres that bear their names. And in politics, it's as if modern-day British leaders were in the habit of quoting, say, Keir Hardie and Kipling.

Jaures in particular is constantly evoked by the left. On the centenary of the Pre-Saint-Gervais meeting last May, they had a ceremony with an actor - in beard and bowler - reading his address from a town hall balcony. At the presidential election, Francois Hollande made sure he spent time at Carmaux in the Tarn department, which was Jaures's political fief.

Jaures's pacifist policies may have been pie-in-the-sky - certainly his critics believed that, if he'd got his way, the army would have been gravely weakened and France overrun - but today, perhaps because of the passage of time, he's untouchable. Even Nicolas Sarkozy, the right-winger, used to tease the left by claiming for himself the Jaures heritage - arguing that at least back then the left believed in the values of hard work.

Peguy has suffered by comparison. It was his great misfortune to be claimed as a hero by Vichy in World War Two, which meant, of course, that ever since he's been taboo. But gradually, today there's a rediscovery of his thought, and the caricature of the nationalist mystic is no longer widely held. Today, it's the patriot who's remembered - a man who saw the war as a clash of civilisations, and who gloried in the chance to defend the right side in European history. Freedom and reason against submission to the irrational. For Peguy, as one writer has put it, the war was Montesquieu against the Valkyries.

In a way you can see them as representing two intellectual constants. For Jaures, the instinct to organise, to bring people together to hasten society's progress, to put faith in peace to the point of naivety. For Peguy, the personal, the intuitive, the yearning for faith - to trust in war, to the point of naivety.

Both men found their beliefs in the ferment of belle epoque Paris - when the city's shine of self-assurance masked anxieties born of too-rapid change, and when history, facing two directions at this turning-point in time, called out for new ideas. In less than six weeks, over the summer of 1914, both men perished for theirs.

Music on the Brink: The Essay series will be broadcast Monday to Friday this week at 22:45 GMT on BBC Radio 3. Yesterday: Vienna. Tomorrow: Berlin.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

Find out more on the BBC World War One website