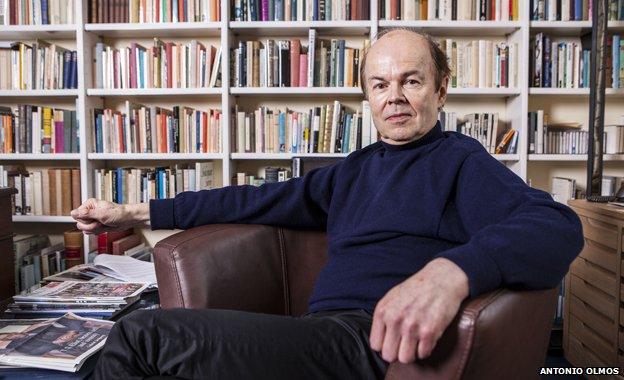

Christopher Jefferies: How I was hounded

- Published

In December 2010, Christopher Jefferies was arrested for the murder of landscape architect Jo Yeates and vilified by the press. Here, in his most personal and emotional account to date, he writes about the far-reaching impact of the episode, even after he was cleared.

The moments between sleeping and waking hover between dream and consciousness, the mind uncertain as to what is fantasy and what is reality.

It was in that state that the knocks on the door announcing my arrest brutally inverted fact and fiction, truth and falsehood, nightmare and the world of familiar reassurance.

I was taken to the police station, unable to think beyond the moment, aware only of what was being done to me by forces I was powerless to influence.

It seemed I was the only one who saw the person instinct told me still existed. Everyone else saw not Chris Jefferies, but the murderer of Jo Yeates.

An individual living out the complex narrative of his own existence was suddenly transformed into a villain.

Jo Yeates was murdered after a night out with colleagues

During the next three days in custody, and then during the three months that followed, everything that seemed stable suddenly became precarious.

As I had to hand over the clothes I was wearing and the possessions I had on me, it was as if the process of stripping me of my identity had begun.

The clothes I was given to wear, the DNA samples, the fingerprints and the photographs that were taken all seemed like attempts to impose an alien persona.

When the doctor examined me, who did she see?

The bare 19th Century cell reflected back at me nothing that I recognised. The distant sounds beyond the sightless windows were the only reminders of a world with which I seemed to have lost contact.

With no watch and with little natural light, time had no shape or structure and events seemed random and haphazard.

As I think about the experience now, I'm acutely conscious of how very different the outcome could have been without friends.

Even as I was starting to think that I needed urgently to arrange legal representation, I was allowed a call from a friend and former pupil who had seen to it that a solicitor was on his way.

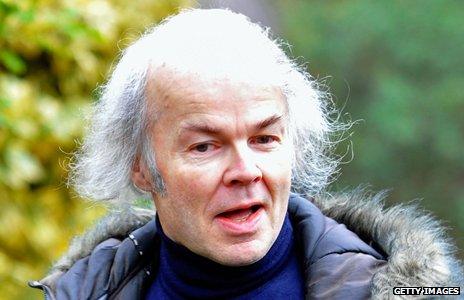

Jefferies in December 2010

That moment of re-connection with life outside a police cell was as if a source of energy had been switched back on.

So too, the calm determination of the solicitor, incredulous at the flimsiness of the case against me, suddenly re-focused my own perspective.

His strength, my anger at what I was being subjected to and the knowledge that I had absolutely nothing to hide gave me back some feeling of control.

I was writing the script, not the police.

From the moment I was released on police bail, I was determined that the wrong that had been done would be put right.

But the following weeks became very much more painful, before I started to feel any real sense of restored identity.

Almost as great as the shock of arrest was the announcement that every item of clothing I possessed had been removed from my flat for forensic examination, and the flat itself would remain in police hands.

I had nothing to wear but the clothes I had been given at the police station and, to add to the feeling of disconnection, even my watch and mobile phone remained confiscated.

I was fortunate to be on my way to stay with the same friend who had made the legal arrangements, but as I was driven away by the solicitor there was the sharp realisation of how unbearably isolated and vulnerable I would still be if I had nowhere to go but a bail hostel.

As it was, for three months I moved between four sets of friends whose lives provided the psychological security without which it would have been almost impossible to cope.

Almost immediately I was made to realise something of the enormity of what had been appearing in the press, and the Dorian Gray-like portrait which was all that existed as far as the world was aware.

But, wisely, I was advised by my friends not to look at the reports.

The process of gradually restoring the identity vandalised by the media was reinforced when, in mid-January, police charged Vincent Tabak, the man who was subsequently convicted of Jo's murder.

But countering that positive and restorative process, and at times overwhelming it, were the stresses and tensions of the fugitive life I had to lead.

I was unable for a time to go out, except occasionally after dark, because the press were desperate for the scoop of discovering where I was. More generally, there was the effect on me of nine weeks of waiting to be cleared of suspicion.

At the time it felt as if the police were deliberately playing a game - promising the ordeal would soon be over and then finding it necessary to prolong the wait.

It was a form of psychological torture.

At such times the mind plays tricks, and one starts to believe that perhaps one is a criminal without knowing it and that, as in some Kafkaesque nightmare, guilt has been pre-ordained and the sentence is inescapable.

When finally, in early March, I was publicly cleared of involvement in the murder, my possessions were returned and I was able to return to my flat.

The slow process of re-ordering every room which, as in a burglary, had been turned upside down during the police investigation, came to seem a metaphor for the emotional and psychological restoration that was still taking place.

Vincent Tabak was found guilty of Ms Yeates' murder

But it was a process made enormously easier by the extraordinarily supportive reaction from neighbours, the local community and beyond.

Somewhat hesitantly and apprehensively, I started to re-connect with my former life.

In fact, I need not have worried since, despite wondering whether I would ever be able to feel at ease in the flat again, the speed with which a sense of normality reasserted itself both surprised and pleased me.

Within another three months, the events of the start of the year seemed a distant nightmare.

It was some 10 months after Jo's murder that I finally learned more of what had been written of me, through Brian Cathcart's analysis of the press coverage, external in the Financial Times Weekend Magazine.

The piece set out some of the coverage that I had avoided - The Sun's use of "the strange Mr Jefferies", "Jo suspect is Peeping Tom" in the Daily Mirror and "Angry 'weirdo' had foul temper" in the Daily Star were all among the many false claims levelled.

The impact was so intense as to be almost physical in its effect.

As the libel action was prepared, I focused only on what the lawyers needed me to read.

Successful actions against eight key newspapers followed, which coincided with contempt of court proceedings brought by the attorney general.

Later I was able to give evidence at the Leveson Inquiry.

It was, I felt, a chance to show something of the reality behind the grotesquely distorting mirror of the press.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external