Belgium divided on euthanasia for children

- Published

Belgium legalised the right to euthanasia for adults in 2002. Now the Senate has voted to extend the law to children who are terminally ill, and suffering unbearable physical pain. Supporters believe this would be a logical move. Opponents say it is insanity.

An incurably sick child, a request to die, a lethal injection. For many people this is an unimaginable, nightmare scenario.

Most of us will not experience the cruel reality of seeing a child's health deteriorate as a result of a terminal illness. But some Belgian paediatricians who have say children should be allowed to ask to end their lives, if they cannot be relieved of their physical symptoms.

"Rarely - but it happens - there are children we try to treat but there is nothing we can do to make them better. Those children must have the right to decide about their own end of life," says Dr Gerlant van Berlaer, a paediatrician at UZ Hospital Brussels.

He and 16 other Belgian paediatricians signed an open letter in November petitioning senators to vote for the child euthanasia bill.

"We are not playing God - these are lives that will end anyway," argues Van Berlaer. "Their natural end might be miserable or very painful or horrifying, and they might have seen a lot of friends in institutions or hospitals die of the same disease. And if they say, 'I don't want to die this way, I want to do it my way,' and that is the only thing we can do for them as doctors, I think we should be able to do it."

Under the draft bill, passed in the Senate last month by 50 votes to 17, children must understand what euthanasia is, and their parents and medical teams have to approve the child's request to die.

In the Netherlands, Belgium's northern neighbour, euthanasia is legal for children over the age of 12, if they have the consent of their parents. But if the Belgian bill is passed in the lower house of parliament, Belgium will be the first nation in the world to lift all age restrictions.

Philippe Mahoux, leader of the Socialist group in the Senate and sponsor of the bill, has described it as "the ultimate gesture of humanity".

"The scandal is that children will die from disease," he says. "The scandal is not to try and avoid the pain of the children in that situation."

A senator who voted against the bill, Christian Democrat Els Van Hoof, thinks it is based on a misplaced idea of self-determination - that everyone has the right to make decisions not only about how they live, but also about how they die. She disagrees, and fought successfully, with a group of other senators, to restrict the scope of the bill to children with terminal illness suffering unbearable physical pain.

"In the beginning they presented a law that included mentally ill children," she says. "During the debate, supporters of euthanasia talked about children with anorexia, children who are tired of life - so how far does it go?"

In the case of adult euthanasia, she fears a "slippery slope" is already in evidence. The 2002 law governing euthanasia allows adults to choose to end their lives, if they:

are competent and conscious

repeatedly make the request

are suffering unbearably - physically or mentally - as a result of a serious and incurable disorder

But two cases of euthanasia that hit the headlines in Belgium and internationally in 2013 left Van Hoof deeply troubled.

In January, the press reported on the deaths of identical twins of 45 who were deaf. Marc and Eddy Verbessem asked for euthanasia after finding out that they would go blind as a result of a genetic disorder - they feared they would no longer be able to live independently.

The death of Nathan Verhelst, a female-to-male transsexual, came nine months later. He asked to die after a series of failed sex-change operations.

Els Van Hoof has been advised by a lawyer that the twins probably did meet the criteria, as they had a serious illness. But the case of Nathan Verhelst still worries her.

It was Dr Wim Distelmans, an oncologist and palliative care specialist and professor at Brussels university VUB, who sanctioned the euthanasia of all three, on the grounds of psychological suffering. He is also the co-chair of the Euthanasia Commission, a panel of doctors, lawyers and interested parties that oversees the law - which, critics note, has not asked prosecutors to examine any of the 6,945 registered deaths by euthanasia in Belgium between 2002 and 2012. All cases are deemed to have been carried out within the law.

On 20 April 2012, Tom Mortier, a chemistry lecturer, got a message to call a Brussels hospital. His mother was dead. Godelieva De Troyer was 64 and had been suffering from depression. She had sent her son an email three months before she died telling him she had asked for euthanasia, but he did not think doctors would allow it.

He is enraged. He does not accept the argument that his mother had a "right to die".

"From my perspective this is not a law for patients, it's a law for doctors so they won't be prosecuted," Mortier says. "Performing euthanasia is unethical. It's killing your patients, and now they're promoting it as the ultimate form of love. What have we become here in Belgium? I don't understand it…"

And his reaction to the Senate vote on children and euthanasia?

"It's insanity."

Dr Marleen Renard, an oncologist responsible for paediatric palliative care at the University Hospital of Leuven, believes there is no need to legislate for child euthanasia, as there are already ways to end the suffering of a dying child.

"If we can't treat the pain, then we can sedate children. And if we see that the situation is really inhumane, we can go to our Ethics Committee and ask for permission to end life. But we have to have the consensus of a lot of people to do that."

For Renard, the critical point is that in her experience, children do not ask to die.

"I've seen a lot of young adolescents with very severe pain and symptoms. They always had some hope for the next day. I've never had one who told me, 'I can't do it any more, please stop it.' They don't want to die. They want to live."

But Dr Gerlant van Berlaer thinks that perhaps children do not ask to die because it is not legal.

"Whenever a child dies in hospital, the other children will talk among themselves," he says. "Often a child will not talk to you directly, but the other children will say, 'We have been discussing it and some of us think we should end our lives another way, different to the way we've seen our friends die.' Once the law changes, they will be able to ask us directly."

Are children really mature enough to make an end-of-life decision? Van Berlaer believes the experience of terminally ill children who spend most of their time with adults often makes them old beyond their years.

Feike van den Oever, a volunteer on the children's oncology ward at the University Hospital of Leuven, agrees children gain maturity when seriously ill. His son Laurens was eight when he died of cancer.

"From the conversations we had with him, you could see how a child starts thinking in a way that is not proper for his age," he says. "Children try to understand what is going on. Does that mean they gain competence to decide or request that kind of solution [euthanasia]? No. Not in my view."

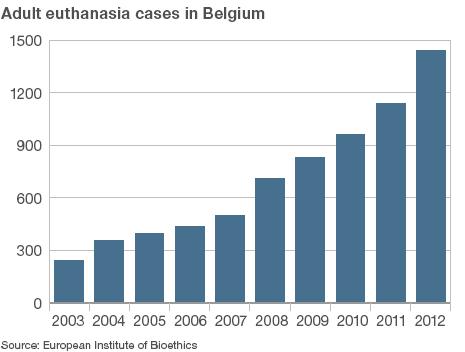

No-one can tell how many children might ask to die if Belgium's euthanasia bill for children becomes law. For adults, the number of requests has increased year on year since 2002. About 80% of those who choose euthanasia have cancer.

"Those cancer patients who die of euthanasia, statistically as a group, live longer than those who die naturally," says Dr Jan Bernheim one of Belgium's early advocates for euthanasia, a pioneer of palliative care, and an oncologist. "Why? Because when it's been agreed that he or she will be able to ask for euthanasia, that reassures people. They know they are going to die well." Spared this anxiety, he says, their illness tends to proceed less quickly.

Bernheim supports the move to extend the right to die to children, and has administered lethal injections to adult patients who asked for euthanasia.

"Suffering trumps all other considerations," he says. "And the way these people die is very ceremonial, and often has some emotional beauty. Whereas, the patient who dies after two or three days of rattling, twitching and grunting, that's terrible…"

The death of a child is a tragedy. But should Belgian children have the right to ask to end their lives? Parliament is expected to decide early this year.

Linda Pressly's report on the right-to-die debate can be heard on BBC Radio 4 at 20:00 on Thursday, or afterwards on the iPlayer

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external