Equality for women at Afghanistan's officer academy

- Published

The UK's lasting legacy in Afghanistan is likely to be the Afghan National Army Officer Academy, which took in its first male officer cadets in October last year, and will admit its initial female recruits this summer. Could it play a role in improving the position of women in Afghan society?

It was a story that was both shocking and depressingly familiar. A young Afghan girl, forced by her brother to wear a suicide vest, and told to blow up a police checkpoint for the Taliban. It happened in Helmand, a place that even here, makes people shake their heads and give a sad shrug that suggests: "Well, what do you expect?"

There was outrage (a little) and dismay (rather more) over Spozhmai's story, but in a country where recent news included a seven-year-old sold for a few thousand dollars in marriage to a 35-year-old so her father could buy drugs, Spozhmai's woes did not trouble the public consciousness here for long.

The story barely made the news after a day or two.

The girls and women we interview here are often those whose lives are extreme, and who symbolise all that is worst or wrong with a place.

I wondered about that when I met two young Afghan women with very different lives, Adila and Arzoo, both university students.

Literature and language student Adila would not look out of place sitting in a Paris cafe - elegantly, though modestly dressed, her eyeliner making her expressive brown eyes even bigger, and her headscarf revealing just a hint of glossy long black hair.

Arzoo, in her fourth year studying physics, is the more earnest of the two, but both are keen to stress just how different their lives are to those of their mothers and their grandmothers.

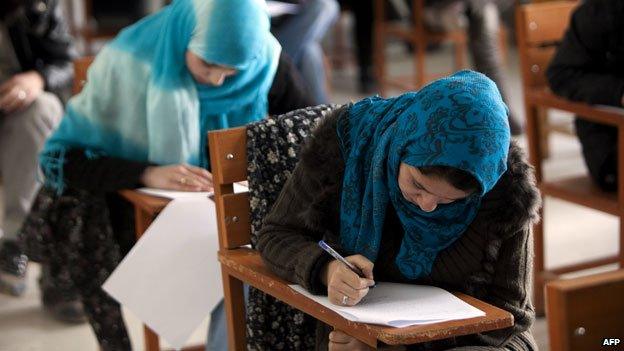

Both remember the Taliban era, when they had to study in secret. Now Adila and Arzoo are determined to help poorer women here to get an education. They believe that remains the key to changing Afghanistan and people's attitudes towards women.

What would they do after university, I asked them. More studies, both said. And if they got married, would they still plan to go out to work? There was an awkward silence. That, they eventually said, depended on their families, and what their husbands thought. It sounded rather as if the answer was No, despite outward appearances.

A few days later, we drove east out of Kabul, the choking traffic thinning as we headed out of the city. But the city limits I remembered from previous trips were no longer there.

Now, new building after new building lined the road - massive blocks of modern glass and concrete flats had sprouted from the sandy soil until they almost blocked out the mountains on the horizon. It was not until we reached the military outpost we were seeking that the city receded, and turned back into the plains I had remembered.

I wondered if these new blocks were seeded by poppy money or fertilised by Western cash, then chided myself for cynicism. There is much new business being done here, despite the high level of dependence on outside support.

The latter was evident when we arrived at "Sandhurst in the sand", the nickname for the new military academy British officers are helping develop as the UK's lasting legacy in Afghanistan.

We were there to meet Sediqa, a quiet, self-possessed 28-year-old second lieutenant, who watched us warily as we arrived. She is the first Afghan female trainer to arrive here ahead of the women officer cadets.

The Academy aims to train 100 female Afghan National Army officers per year, or about a 10th of the total, with the first intake to be chosen this April. They are due to start in June, and recruits will spend a year here before they graduate.

Sediqa told me she had joined the Afghan army because she wanted to serve her country, as her brother and sister-in-law already did.

I asked if she was worried by the deaths and injuries her army was suffering in Helmand and elsewhere - more than 1,000 killed in 2012 alone, and more than 3,000 seriously injured. Women police officers and officials have been targeted specifically in provinces such as Helmand, though Afghanistan's women soldiers will not be expected to perform frontline fighting roles.

Sediqa nodded thoughtfully, but said it had not put her off. Her husband was also happy for her to serve.

As for female equality in Afghanistan, her raised eyebrows said it all. Sediqa was not sure we could even begin to talk of equality for women in Afghanistan. Even men did not have many rights, she said, and females far fewer.

The TV and radio news were full of stories about violence against women most days, she said. Once you could begin to talk of human rights, then perhaps one day, she told me, women's rights could start here too.

But Sediqa's British mentors are keen to make sure that women are treated equally here.

In the large and airy gym, Afghan male officers and trainers are having to get used to training alongside women - including British physical training instructor, Staff Sergeant Kate Lord. She has been training the men, giving orders via an interpreter.

"At first, I didn't know how they'd take me - but after they saw me doing all the physical elements, that won me their respect. I get on with the guys really well," she smiles.

Kate is now focusing on training the three Afghan female sergeants who'll be training the cadets when they arrive. She says that they are have not been used to performing tough physical exercise in the past, and are taking to it - for the most part - with enthusiasm.

"It feels really good to be doing the one-on-one mentoring, it's historic to be here doing this at this time, and it feels as though I am making a difference."

Fluent Pashto and Dari speaker Major Claire Brown, who has been helping set up the women's course, after an earlier tour of duty in Helmand Province, is realistic about the challenges that the women who study here will face within the Afghan Army - as well as wider Afghan society.

"Anybody in the Afghan security forces has to have concerns about their own personal security. Of course, they have their own cultural issues they have to face and I hope that we can help to prepare them," she says.

"Anybody who is joining this army as a woman is a pretty brave person to start with, and we hope to develop that during the training."

The wider hope is that the Sandhurst ethos will translate to this very different culture, and bring the leadership Afghanistan wants from its army, and perhaps - in doing so - also help women in their long, slow march to greater equality in a deeply conservative society.

From Our Own Correspondent, external: Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external