North Korea's storytelling autocrats

- Published

North Korea's leaders are often thought of as ruthless, secretive autocrats but rarely as popular children's authors. However, between issuing instructions about prison camps and the development of nuclear weapons, Kim Jong-un's father and grandfather apparently found time to write stories for the young.

"At last the left cyst burst, emitting fierce flames and the captain fell down, dejectedly dropping his club. At that moment a loud battle cry was heard from outside. Villagers killed the rest of the bandits."

This is an extract from Boys Wipe Out Bandits by Kim Jong-il - North Korea's "Dear Leader" who died in 2011.

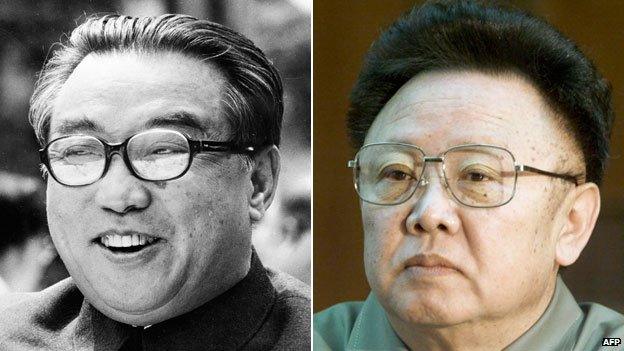

Kim Jong-il and his father, Kim Il-sung, recognised the power of books and they are both credited with writing children's stories.

This one is "an extraordinarily violent and exuberant tale," says Christopher Richardson, who is researching North Korean children's literature at Sydney University.

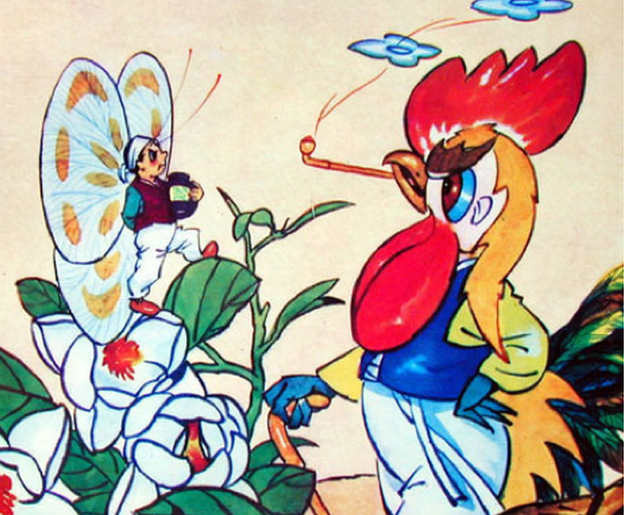

Illustration from Boys Wipe Out Bandits

It is a story "of reactionaries and bandits and gluttons lurking in the hills of North Korea, predating on the pure-hearted and virtuous villagers who incarnate all of the traditional virtues of the North Korean revolution," he says.

The heroes are a group of brave youngsters who stand up to the bandits. Despite its political message, Richardson thinks it would be wrong to dismiss tales like this simply as propaganda.

"They can be quite fun to read and they're actually quite good yarns, and I imagine children aren't even that aware of the ideological content," he says.

"If you made a cartoon of Boys Wipe Out Bandits and showed it to a bunch of Western six-year-olds or eight-year-olds they'd go nuts for it. They'd love it because it's the same kind of silly violent nonsense that boys everywhere tend to like."

Kim Jong-il also wrote a treatise on literature dedicating a chapter to children's books - he favoured the use of parables and satire to criticise enemies of the state.

The villains in the stories vary - in Boys Wipe Out Bandits they are wayward Koreans behaving like feudal landlords, not thinking of the collective, out of touch with the revolution and Juche culture.

The Juche ideology, developed and promoted by Kim Il-sung, sees man as the master of everything with the power and responsibility to make the revolution a success. It values North Korean self-reliance and independence from foreign powers.

There are plenty of anti-American tales reflecting this philosophy, such as The Butterfly and The Cock, a fable ostensibly first told by Kim Il-sung and later written down.

It tells how a cockerel - symbolising the US - tries to ruin an idyllic garden and bully the other animals but a plucky young butterfly - representing North Korea - stands up to the invader and saves the day.

Foreign marauders from an earlier age feature in another of Kim Il-sung's tales, A Winged Horse. The book recalls a time when the country was threatened by Japanese invaders and pokes fun at samurai with unflattering descriptions and illustrations.

This time a cherubic child comes to the rescue riding a flying horse, willing to sacrifice his own life for his village.

Richardson questions whether the leaders really wrote these books themselves. His scepticism is echoed by Lee Hyeon-seo who grew up in North Korea but left when she was 17. She has clear memories of the books she and her schoolmates were given when they were young.

The tales she remembers most clearly recounted Kim Il-sung's heroic battles against the Japanese "and some ridiculous stories about Kim Jong-il... when he was five he killed some enemies - he just shot them down," she says.

Kim Il-sung (left) led North Korea from 1948 to 1994 - he was succeeded by his son Kim Jong-il (right)

"It's impossible but we just believed as children because for us they are not human beings, they are like our Gods."

The books "don't usually tell the truth, they usually tell all the fake things," says Lee. She was taught that the US had colonised South Korea and executed students, South Koreans were begging, couldn't afford to go to school and that healthcare in the south was so expensive patients died outside hospitals.

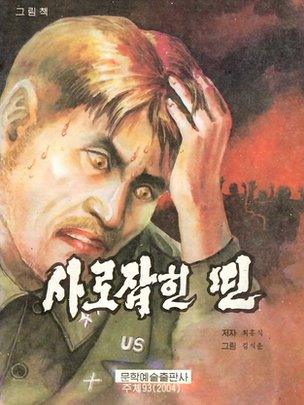

Some books by state approved authors are based on real events - Dean Captured recounts how a US officer was caught in the Korean War

When she was very young, Lee was allowed to read foreign picture books such as Cinderella. As she grew up, though, she found that some books were restricted - texts about Lenin and Marx were banned, for example, as they discussed an alternative approach to communism.

The current leader, Kim Jong-un, is aware that he needs to find a way to keep today's children and teenagers loyal to the state his grandfather created. He has invested in a new water park and cinemas.

Western influences have occasionally crept in. State television has shown the odd Western movie, such as Madagascar, and two years ago Disney characters danced on stage at a concert by the Moranbong band - a girl group put together by Kim Jong-un himself.

Richardson says this decision not to quarantine foreign culture was revolutionary - but short-lived.

"Since then, there has been a swing more or less back in the other direction," he says. The state is "very paranoid about the corrosive effect of foreign children's culture," and is hoping that giving people a small taste of the West will be enough to keep them satisfied.

Christopher Richardson spoke to World Update on the BBC World Service.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external