Winter Olympics: The drama of the Games

- Published

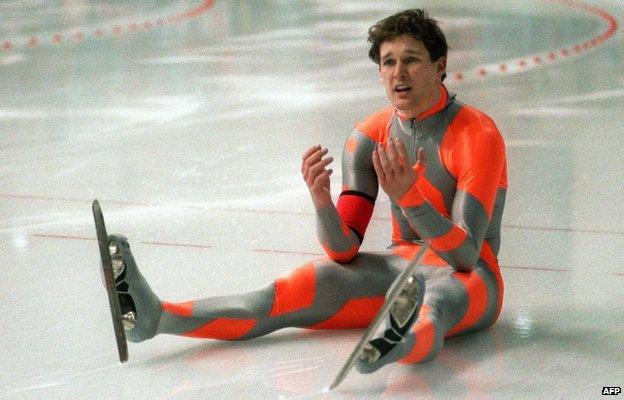

Dan Jansen after his fall in the 1000m race, Calgary 1988

As athletes prepare to take part in the Sochi Winter Olympics, competitors from previous years share the drama and emotion of their own personal stories.

The bereaved skater

At 06:00 on the morning of his race in Calgary, Canada, in 1988, US speed-skater Dan Jansen got a phone call. His sister Jane was in hospital with leukaemia. "Mum said she wouldn't make it through the day most likely and so - tough day.

"Once I got on the ice there was nothing there, there was no stability in my legs, my skates didn't feel like they were my skates, I think I was just shaky."

He made a false start and when the 500m race finally got under way his left skate slipped and he fell. Sitting on the ice in Calgary he felt confused. "I didn't know if I should feel bad for falling in the Olympics or [that] my sister died." He fell again in the 1000m.

In 1994 in Lillehammer, Jansen was again the favourite to win the 500m. But on the last turn he slipped and finished eighth. He had one last shot at gold - in the 1000m, but he would have to beat his own personal best time.

Once again he slipped but kept his footing. "Something in me didn't panic this time… I stayed calm." He set a new world record and won the gold medal. "With my sister and all of it - it wasn't just a race, it was much more than that."

He had become tired of everybody feeling sorry for him. "This was better. Now they could actually be happy for me."

A bolt from the blue

After his first bobsleigh run, Robin Dixon from the British team checked the sled. "One of the bolts that held the rear axle was broken," he says, remembering the 1964 games in Innsbruck, Austria.

The British mechanics couldn't find a spare, but one of the greatest Winter Olympians of all time, Italy's Eugenio Monti, stepped in.

"He said: 'Don't worry, this is my last run for the day. When I've finished, send an Englishman down with a spanner and you can have mine.'"

Monti kept his promise and handed over the bolt from his own sled. The following day the British team raced before the Italians. Dixon and his partner Nash didn't think they had been fast enough to win so they went off to drink coffee and schnapps.

But when they heard the track was deteriorating, they rushed back to the course to see Monti finish 0.7 seconds behind them. The Italian came straight over. "He was genuinely delighted for us," says Dixon.

"It was a lovely gesture and really exceptional… I am a very determined, competitive animal... and I wouldn't have done it."

The International Olympic Committee gave Monti the Pierre de Coubertin medal - named after the founder of the modern Olympics and given to athletes who show the spirit of sportsmanship. It's an honour far rarer than a gold medal.

'A kind of Cold War'

Katrina Witt recalls the "Battle of the Carmens"

In an incredible coincidence, East German figure skater Katarina Witt and her biggest rival, Debi Thomas from the US, both chose to dance the part of Carmen - the Spanish gypsy immortalised in Bizet's opera, in the 1988 Games in Calgary.

Witt emphasised the sex and death in the score, wearing heavy make-up and a red-and-black flamenco dress, while Thomas went for a lighter, more athletic interpretation in a black costume.

Witt was desperate to retain her Olympic title. "It was the battle of the two Carmens, and it was some kind of Cold War," she says.

"I was from East Germany and at the same time I was representing something which was more grey and more cold - that was the perception people would have."

Debi Thomas was representing everything that is good about America, recalls Witt. "The democracy and the freedom, and she was of course one of the first black skaters."

One of Witt's jumps didn't go as planned leaving her riddled with doubt. But when Thomas also made mistakes Witt came away victorious, feeling more relieved than excited. She celebrated with a glass of sparkling wine and a sausage.

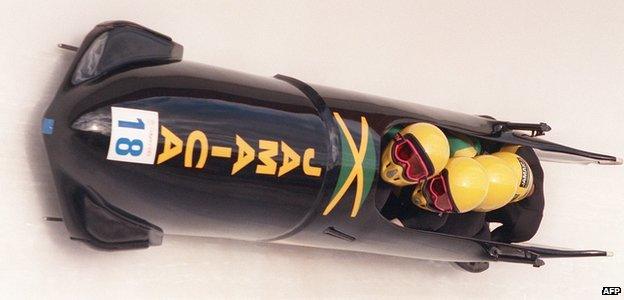

The real Cool Runnings

"It was fast and dangerous." Six months before the 1988 Winter Olympics, that's all Jamaican army officer Devon Harris knew about the bobsleigh.

Jamaica had never been to the Winter Olympics before but two US businessmen, George Fitch and William Maloney, decided to change that by creating a Jamaican bobsleigh team.

"We couldn't even walk on the ice - we spent more time on our butts than we did actually running," says Harris remembering their first training session.

When they got to Calgary, Harris was "scared to death but I was having a ball".

They switched one of the team members at the last minute and ended up with the seventh fastest start time. But on the next run the sled hit the wall. "The next thing I knew my head was hitting the ice. I just remember thinking 'wow how embarrassing we crashed in front of the entire world.'"

The crowd cheered and said "We love you, we love you," but the team was worried about going home. "We thought we would be ridiculed and chased out of town, and it couldn't have been further from the truth."

Their faces appeared on stamps in Jamaica and their experience inspired the 1993 film Cool Runnings.

The assault

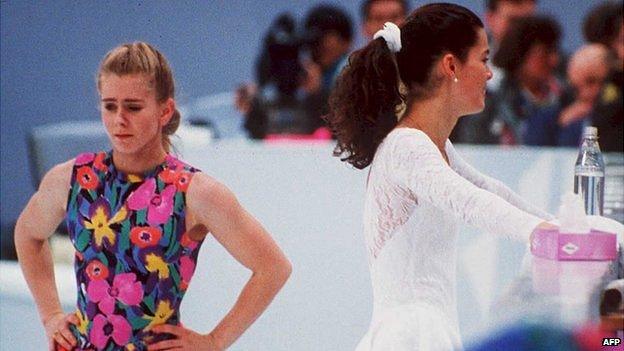

Tonya Harding (left) walks past Nancy Kerrigan during a practice session in Norway

"There was a huge scream and somebody came running and told us that Nancy was on the ground," says Mary Scotvold, the coach of American figure skater Nancy Kerrigan. It was just weeks before the Winter Olympics in Lillehammer in 1994 and Kerrigan was screaming in pain during a practice.

"She was understandably hysterical, but she knew that a man had hit her hard on the knee and knocked her down."

Her assailant fled, and doctors said if his aim had been slightly different, Kerrigan would never have walked again. The attack was planned by the bodyguard and the ex-husband of rival American skater, Tonya Harding.

Harding admitted that while she had no role in planning the attack, she had covered up later knowledge of the incident. Four men were arrested including her ex-husband Jeff Gillooly.

The US Olympic committee began proceedings to remove Harding from the Olympic team, but she kept her place after threatening legal action. Seven weeks after the attack, Kerrigan skated at the Lillehammer Winter Olympics, purposely wearing the same dress she wore when she was attacked.

Nancy Kerrigan won silver, with Ukrainian skater Oksana Baiul taking the gold.

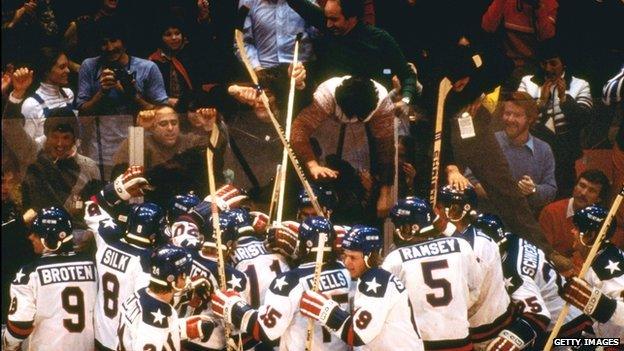

A miracle on ice

In the midst of the Cold War, at Lake Placid in New York state in 1980, two global superpowers clashed on the ice.

The USSR's Big Red Machine had won four Olympic gold medals in a row dating back to 1964 and expected to win the ice hockey semi-final against Team USA.

"We were basically a bunch of college kids playing against very skilled and very talented pro players from Russia," says Neal Broten, from the US side.

The Soviets were confident of victory. "We had beaten them soundly right before the Olympics so we weren't worried, we thought we would beat them easily," says Alexei Kasotonov from the Soviet team.

Inside the arena, the atmosphere was electric. As expected, the Soviets dominated the start of the game, but the US fought back and defied all expectations to win the match.

"The fans were going crazy… it was nuts in that arena," says Broten. "I don't even think our skates were touching the ice. If we played that team 10 times we would lose all 10 games." To beat them in our country was an achievement that rarely happens, he adds.

Team USA went on to win the gold medal. But the Soviet team and Alexei Kasotonov made a comeback, winning gold in 1984 and again 1988.

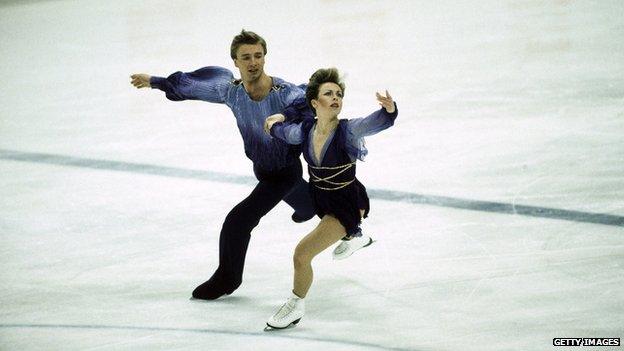

6.0, 6.0, 6.0, 6.0, 6.0, 6.0, 6.0, 6.0 and 6.0

It was Valentine's Day when the UK's Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean took to the ice in Sarajevo in 1984.

As they knelt, swaying to the haunting strains of Ravel's Bolero, they knew they were stretching the rules.

Dance routines could be no longer than four minutes and 10 seconds, but despite their best efforts, Torvill and Dean couldn't cut the music short enough - it was still too long.

To get around the problem they made sure their skates didn't touch the ice for the first 18 seconds - the clock only started ticking when the first blade made contact.

"It was unique for the time," says Dean. "We created that mood, that swirling, that intimacy right from the beginning which set the tone for the rest of the routine."

Some worried that the judges might find the routine too radical, but the former insurance clerk and police officer made history with their sensual dance.

In front of one of the UK's highest ever television audiences, nearly 24 million people, they received 12 perfect scores of 6.0 out of a possible 18. Most remarkable was the straight row of 6.0s for artistic impression from all nine judges - something that had never been achieved before.

"Our closest rivals were always the Russian skaters," says Torvill. "So to get a 6.0 from a Russian judge felt like a big deal. He could have given us a 5.9, but he didn't - it was a magical moment."

The embrace at the finish

When Kenya's first Winter Olympian, cross country skier Philip Boit, approached the finish line in Nagano in 1998, the crowd went wild.

"They were shouting 'Kenya GO!, Philip GO!' It was like I was winning a medal even though I was last," he says.

The winner of the 10km classic style event, Norway's Bjorn Daehlie, had finished 20 minutes earlier, but instead of going straight to the medal ceremony he waited for Boit, and hugged him when he finished the race.

Boit had not even seen snow until two years earlier and on the day of the 10km classic style event, heavy rain made conditions unusually tough. "I fell down so many times," laughs Boit. "Going uphill, the skis were collecting snow. It was like I had put on high heeled-shoes!"

Daehlie, who became the first man to win six gold medals at the Winter Olympics, was impressed that Boit was able to finish the race in such tricky conditions. "I wanted to wait [for him at] the finish line - this African, brave skier."

The embrace was a special moment for Boit - "I couldn't believe that he was the top guy and he was holding me."

Boit skied again at the Salt Lake Winter Olympics in 2002, but not against Daehlie who was recovering from a roller-skiing injury. He named his first child after the Norwegian icon and the two athletes are still friends.

Sporting Witness is broadcast on the BBC World Service. Listen via BBC iPlayer Radio. Browse the Sporting Witness podcast archive.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external