The slow decline of American Chinatowns

- Published

The BBC visits New York's Chinatown for the new year celebrations to see how the community is changing

Chinatowns are a feature of many US cities, but some of the best known are succumbing to gentrification, campaigners say. Even one of the largest and most vibrant, in Manhattan, is slowly being invaded by luxury shops and apartment buildings.

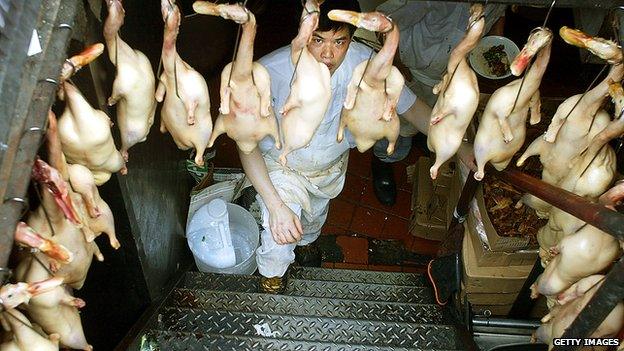

It's late afternoon and Mei Rong Song is serving a few last customers in Lao San Snack on East Broadway. Giant metal pots steam behind a counter stacked with metal trays of pig's blood, heart and intestines.

Mei has run her restaurant for a decade, catering to a wave of immigrants who began arriving in the 1980s from Fuzhou in south-eastern China.

But high rents have been pushing Chinese immigrants out of the area, their place taken by wealthier white tenants.

"My shop has Fuzhou speciality foods, and as Fuzhounese people stop living in this neighbourhood there's less and less demand for what I sell," she says.

"I don't know that I can stay for more than a year or two."

Rapid immigration led to the formation of US Chinatowns in the late 19th Century, though a long period of exclusion and discrimination for the Chinese began around the same time. The next large wave of arrivals followed the 1965 Immigration Act, but in recent decades older Chinatowns have shrunk.

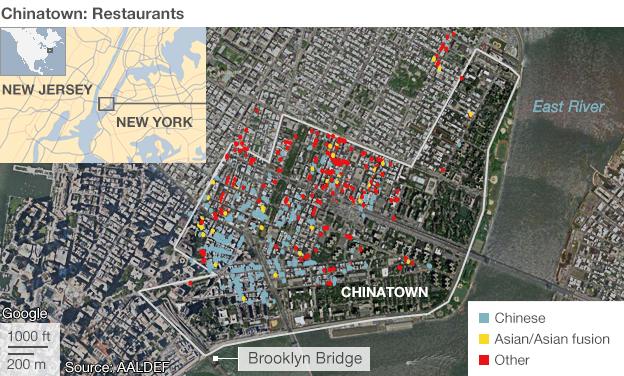

"Chinatowns are turning into a sanitised ethnic playground for the rich to satisfy their exotic appetite for a dim sum and fortune cookie fix," says Andrew Leong, one of the authors of a recent report, external that charted gentrification in New York, Boston and Philadelphia's Chinatowns.

Washington DC's version is little more than a collection of Chinese restaurants, gift shops and an ornate arch.

This is partly a result of the success of Chinese immigrant families. Many of those from Manhattan's Chinatown have moved to younger Chinese neighbourhoods in Flushing, Queens and Brooklyn's Sunset Park.

But up to now, new arrivals in New York have always taken their place.

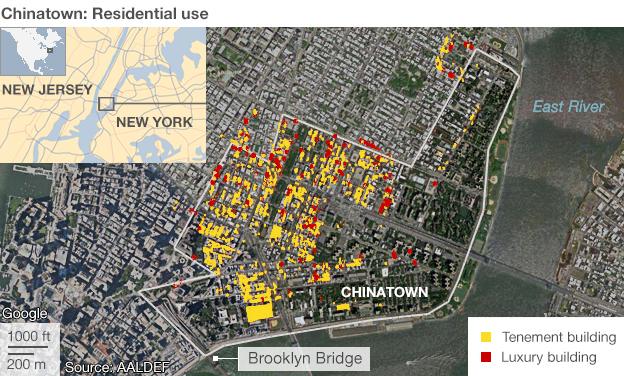

Thousands of working-class families still live in Chinatown's humble tenement buildings, protected by the city's rent-control laws. English is seldom used for business. On an icy winter's day, shoppers stop at stalls selling Chinese delicacies, and cluster in a basement fish and vegetable market.

"It's remained a very dynamic immigrant centre for 100 years because it's retained its ability to be an immigrant gateway - a place where new immigrants come in and are able to find housing and job networks," says Ken Guest, an anthropologist at New York's Baruch College. "East Broadway is the first stop as people try to figure out how to make their way in the US economy."

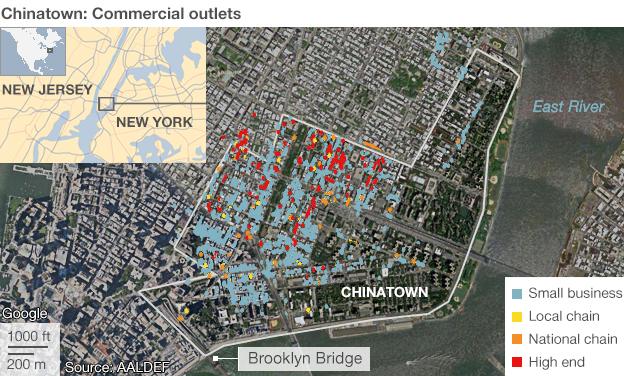

Services on offer there include immigration agencies, Chinese doctors, herbal shops, lawyers, phone card companies, banks and wire transfer firms.

Employment bureaus send people out to jobs in restaurants on Chinese-run bus routes that stretch as far as the Rockies. An estimated 50,000 people are passing through this network at any one time, says Guest.

It's this community that has preserved Chinatown's special character. The shop signs, the language, the groceries, the aroma of the restaurants are unlike those of any other Manhattan neighbourhood. Visitors to Chinatown have entered a subculture.

Yet things are changing.

The report on gentrification, published by the Asian American Legal Defense Fund, finds that from 2000-2010 the share of the Asian population has fallen from 48%-45% in New York's Chinatown, 57%-46% in Boston's, and 49%-30% in Philadephia's, and that the share of the white population rose in all three cities.

As local government encourages commercial development, low-income families and small businesses have been displaced, the report says.

The process is less advanced in New York, says Andrew Leong. But even there high-end stores, non-Asian restaurants and luxury apartment buildings have been spreading.

Former garment factories have been converted into expensive lofts and landlords have illegally evicted low-income residents, the study says.

This story is echoed by Zheng Zhiqin, a campaigner who has noticed growing pressure on low-income tenants, many of them Chinese, over the past 10 years.

"They're encouraging people to leave all the time. Sometimes by not providing hot water, or adequate heat, and raising the rents as high as they can," she says. "I see this happening all over Chinatown with my neighbours and friends, and in other buildings in the area."

Zheng says big celebrations for Chinese festivals allow immigrants to feel "very much at home" in Chinatown. But this year her landlord, keen to keep the building tidy, asked her for the first time not to hang a traditional bright red scroll from her front door for Chinese New Year.

Increasing numbers of immigrants live outside Chinatown and come in for business during the day, or a weekend shopping trip.

Cynthia Koo, a 26-year-old start-up employee who went to elementary school in Chinatown, says that all but one of her childhood friends have left the neighbourhood. Her mother used to work in the garment industry before its rapid decline in the 1990s and her father manages a Chinatown restaurant that she says now serves non-Chinese communities.

"I think it's a little sad," she says. "It definitely from my experience feels a lot less lively."

But some argue that Chinatown has to adapt in order to survive.

Wellington Chen, who runs a community network formed to help the neighbourhood recover after the 9/11 attacks, thinks the focus on gentrification is misplaced.

"At the end of the day the narrow splitting of us versus them - the class differentiation, the gender, the race thing - that's nonsense," he says. "The best communities, just like the best individuals, are the ones that can adapt to changes very flexibly, nimbly, quickly."

Chen supports Chinatown's Business Improvement District (BID) scheme, which uses levies from local business owners to pay for projects to spruce up the area. Keen to make the area more welcoming to outsiders, Chen would like to see waiters speaking better English and has expressed support for the construction of an eye-catching Chinatown arch.

It's ideas like this that feed Andrew Leong's fears of an "exotic playground" for wealthy visitors.

Some recent research, external suggests that gentrification can actually benefit an area's original residents. Though vulnerable tenants can be pushed out, those who stay may benefit from improving services and better credit ratings.

But Peter Kwong, a professor at New York's Hunter College, says that while this may apply to struggling communities in areas suffering from industrial decline, it doesn't apply to Chinatown.

That explains local resistance to the BID and to "rezoning" laws that allow for future property development, he says.

"Manhattan is practically all gentrified - this is one of the last areas," he says.

"There is a lot of money targeting this area, that would like to see this place [become] a destination for tourism - a quaint place, kind of a hip place for rich people with an ethnic flavour."

Bonnie Tsui, author of the book American Chinatown, says that when Chinese communities decline "there is this larger sense of loss of that everyday vibrancy that a neighbourhood like Chinatown has".

Visitors "like that concentration, they like that richness of experience, they like that people are speaking in a different language because it feels foreign yet familiar," she argues.

"They don't really see that in many neighbourhoods any more."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external