Has the UK truly 'stocked up' on rainwater?

- Published

Hard as it is to believe now, two years ago the UK was seriously preparing for drought. Since then there's been a lot of rain, so does it mean there won't be hosepipe bans for many years?

It's been wet. December last year was the sixth wettest on record for the UK and the wettest ever measured in Scotland. There was no let-up - January this year was the wettest in southern England since records began in 1910.

All this after a generally wet 18 months means that where there isn't flooding, the ground is sodden.

Yet not too long ago the UK suffered from wildfires, hosepipe bans and fears over drying aquifers. Between April 2010 and March 2012 England and Wales experienced one of the 10 worst droughts, external of the last 100 years, according to the Met Office.

So how long is the UK's grace period before water shortages become a possibility again?

In April 2012, after two unusually dry winters and with water companies bringing in restrictions, the Magazine ran a piece entitled "Eight radical solutions for the water shortage". Then the heavens opened. For the next month it barely stopped raining. It was the wettest April since records began.

There were flood alerts across England and Wales. And yet parts of the country were still officially in drought, prompting the Magazine to ask on 1 May, external: "How much rain is needed to ease the drought?"

It turned out the answer was a lot. Experts warned that it was the wrong time for rain. In spring and summer there would be too much evaporation, they said. Winter rain was what was needed to top up the aquifers.

Dr Adrian Butler, a reader in subsurface hydrology at Imperial College London, then estimated that the Midlands and south of England needed twice the normal summer rainfall for groundwater to recover. It seemed unlikely it would happen.

Summer 2012: The wrong kind of rain

May 2012 saw slightly less rain than average. But in June and July the biblical weather returned - with rainfall above and just below 200% of the average respectively. We didn't know it then, says Prof Nigel Arnell, director of the Walker Institute at Reading University, but the summer rain had more effect than anyone anticipated. "In practice what happened in 2012 was that there was so much rain that it overwhelmed evaporation."

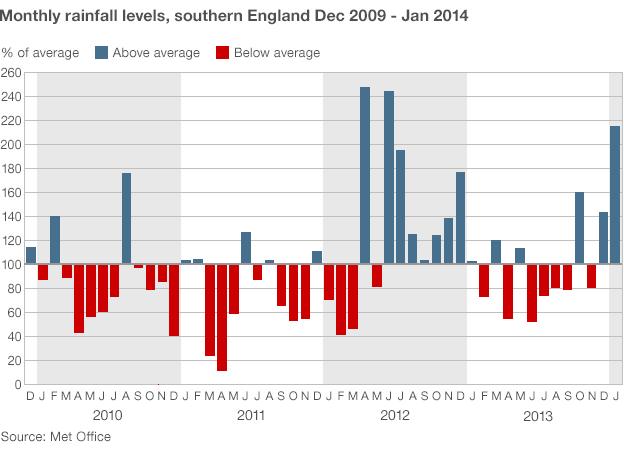

Since then higher than average rainfall has occurred more often than dry spells. The Met Office chart tells the story. Before April 2012 there is a wall of red, signifying clusters of dry months, with only the odd blue vertical line, denoting wet months. But after April 2012, blue heavily outnumbers red.

A rule of thumb that experts agree on is that the UK can generally cope with one dry winter. Two in a row and you have a serious problem.

But what about two wet winters in a row? How useful is this for the future? Water supplies in the UK are now extremely healthy, experts agree. "All the water in the soil and ground is now banked," says Trevor Bishop, head of water resources at the Environment Agency, which oversees England's supply.

The long wet period has built up big water stores in the ground (known as groundwater). Aquifers in the rock act as underwater reservoirs, catching water that drains through the soil, releasing small quantities gradually into springs. Groundwater provides the water companies - via pumping - with about 30% of the water consumed in the UK, says Rob Ward, a director at the British Geological Survey. In parts of south-east England, such as Kent, the majority of water comes from aquifers.

Groundwater levels were very high last winter, and early indications suggest they will be exceptional this year, says Jamie Hannaford, senior hydrologist at the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology. "We only have data for selected chalk boreholes but we have already seen some exceptional late-January levels," he says. "We anticipate these levels to be widespread across southern England, with new records in some places."

At Tilshead, a borehole on Salisbury Plain, groundwater levels rose by 20m in a fortnight from the end of December to early January, he says. It's the steepest increase since measurements began at Tilshead. The Chilgrove House well in West Sussex was overflowing in late January, something that has only happened six times since 1836.

The country is safe from drought for all of 2014 and probably 2015, Bishop believes. The worst drought on record was the summer of 1976. Even if the UK gets similar levels of rainfall (about 60% of the average) from tomorrow, it would be another 6-12 months before the aquifers dropped back to normal levels - the variation depends on rock porosity in different areas. It would then be another 6-12 months before the depleted aquifers caused water shortages.

Not good weather for ducks

For a drought to occur three things are necessary, Bishop says - a hot, dry summer in 2014, a dry winter in 2014-15 and another very dry summer in 2015. It's very unlikely all three will happen, he says.

Thames Water, the UK's biggest water company, broadly agrees. It supplies the capital with water taken from the River Thames or the River Lee and stored in large reservoirs.

"The last time we had such a long wet period was in 2000 and 2001," says Stuart White, the firm's media manager. "We didn't experience any potential difficulty until the very hot summer of 2003. Even then water use restrictions were not needed."

Others are more cautious. "I think you can rule out hosepipe bans for 2014," says Prof Arnell. But beyond that it's hard to say. If next winter is dry, next year could see shortages, he argues.

Hosepipes: Safe for now

Groundwater is not the only factor. In the north of England, aquifers are less influential so regular rainfall is important to keep rivers and reservoirs supplied. In the 2012 drought the hosepipe ban began in north-west and not south-east England.

Some areas - parts of eastern England and the far north of Scotland - have bucked the trend and had less rainfall than average, says Hannaford. And while reservoirs are nicely topped up now, 2015 may be a different story.

"We can say that the current wet winter decreases the chances of a major drought in 2015. But a single dry winter can be influential and if winter 2014-2015 is dry there could still be drought stress the following year."

The surprising drought of 2010-12 and the equally unexpected wet summer that followed, should prevent weather complacency. As should the reality - rather than just the hazy memory - of summer 1976.

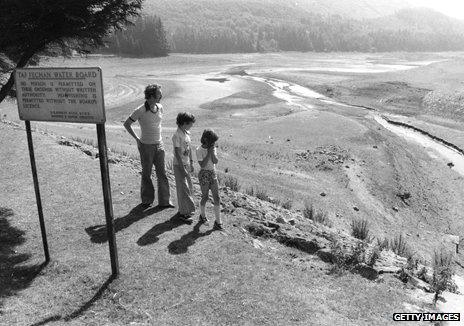

A dry reservoir in South Wales, 1976

It wasn't just a hot summer, says Hannaford. "The extreme drought of 1976 is associated with the summer heatwave. But the event was also driven by a lack of replenishment of water resources during the previous exceptionally dry winter."

In short, a drought is looking unlikely for 2014 and probably 2015. But extreme weather can quickly defy received wisdom.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external