Vietnam's illegal trade in rhino horn

- Published

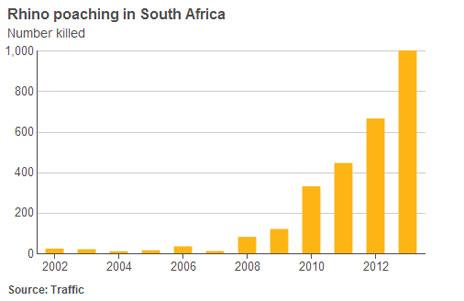

Record numbers of rhinos are being poached and killed in South Africa for their horn. Many of those horns end up being sold illegally for their supposed medicinal properties - in countries such as Vietnam.

On 30 December 2013, a park ranger on patrol in South Africa stumbled across the body of a two-tonne, 3m-long dead rhino. Its horn had been torn from its face and it had almost certainly died in slow agony. The ranger used his radio to contact the park HQ saying simply, "Another one gone."

They knew immediately what he meant.

The death took the number of rhinos poached and killed for their horn last year to 1,004, a 50% increase over the previous year. The South African department of environmental affairs says 668 were killed in 2012. A decade ago, in 2003, only 22 rhinos were poached.

If it continues at this rate, the African rhino could face extinction, according to Naomi Doak of the respected wildlife monitoring network, Traffic.

"We are going to reach the tipping point for rhinos," she says. "By the end of 2014, we're starting to be in the negative in terms of deaths and poaching outstripping birth and the population will start to decline very quickly."

Traditional Medicine Street in Hanoi bustles with street vendors balancing their wares on bicycles while dodging cars. People crowd on to the pavement to drink tea, smoke and play card games. It feels a world away from the vast plains of the South African veldt. But these two worlds are inextricably and, for the rhino, tragically connected.

I am told it is the place to buy rhino horn in Hanoi, so I decide to see how easy it is.

Journalists are closely monitored, though, in this one-party communist state, so my minder is never far away. It has been illegal to buy or sell rhino horn in Vietnam for eight years and the traders all shake their heads at my request to buy. "It hasn't been sold in the street for a long time," says one.

But when I return later - without my minder, and with a hidden camera - traders are happy to oblige. I claim to have a sick husband. One trader tells me that if I grind the horn in to powder and mix it with alcohol, it will cure his cancer. "For the middle stage of cancer, it has a 85-to-90% success rate," he says.

At $6,000 (£3,660) for 100g (3.5oz), it is more expensive than gold in Vietnam, at current prices. And yet, biologists say, the main component of the rhino horn is a material similar to the human finger nail.

I go to another who claims he is a traditional medicine doctor and say I am looking for a hangover cure. "You've come to the right place," says Mr Nguyen, and shoves a large piece of rhino horn in my hands. "It cures fever and is good for removing poisons from the body which makes it a good remedy for hangovers."

Sue Lloyd-Roberts is offered rhino horn for sale during undercover filming

I have been warned that a lot of the horn sold on Traditional Medicine Street is fake and I ask Nguyen to reassure me. "I went to South Africa myself," he says and shows me his hunting permit to shoot two rhinos in 2009. His wife accompanied him and he has a picture of his eight-year-old son standing beside an animal he shot and killed.

He shows me documents, all stamped by the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (Cites), which approve the export from South Africa and the import to Vietnam of a "trophy horn". He tells me all this makes the sale perfectly legal. But it is not.

Most of the rhinos in the wild are found in South Africa where the black rhino is considered endangered and the white rhino remains in the threatened category.

Nonetheless, rhino hunting is permitted under strict rules - fewer than 100 experienced hunters can apply for a permit every year to shoot just one rhino and they're legally required to keep the horn intact, as a trophy. The argument is that hunting encourages privately owned rhino parks and therefore adds to rhino numbers. Permits costing tens of thousands of dollars contribute to the local economy.

In 2010, the last Javan rhino in Vietnam disappeared, a subspecies hunted to extinction. As the Javan rhino became scarcer at home, Vietnamese hunters started applying for South African permits. By 2010, there were more Vietnamese applying to shoot a rhino in South Africa than any other nationality.

But, like Nguyen on Traditional Medicine Street, they were found to be abusing the system. Against the rules, they were importing the horns back to Vietnam and selling them. When South Africa banned Vietnamese hunters in 2012, organised crime syndicates took over who now employ poachers to supply the market for horn in Vietnam and other Asian countries, including China.

Vietnam became a signatory to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species 20 years ago. The Cites secretariat has been urging the Vietnamese government for some years to tighten the laws and penalties against those selling horns. They were expected to have new laws in place in time for a conference on illegal wildlife trading being held in London this week.

I asked Do Quang Tung, who is charged with getting his government to comply with Cites demands, why it is taking so long? "Well, in order to prepare any regulation or law, you can't just make it in one year, it takes time you know," he says,

The trouble is, the wildlife experts say there is no time.

Mary Rice, executive director of the Environmental Investigation Agency warns: "What we are witnessing right now is the wholesale slaughter of a species, being poached to supply what is ultimately a growing and unsustainable market in Vietnam - and elsewhere. The international community should urgently focus its attentions on pursuing and convicting the criminals behind the organised networks perpetrating the trade."

Sue Lloyd-Roberts reports from Vietnam for Newsnight

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external