The international swap trade in useful words

- Published

A recent Magazine article explained how the English language borrows words from other languages with a truly global reach.

Philip Durkin, deputy chief editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, showed how patterns of borrowed words reflect complex patterns of cultural contacts across the centuries - with more than 50 examples. Here he looks at readers' own favourite examples.

Many readers' responses picked up on how various clusters of borrowed words can illuminate multilingual, inter-cultural encounters in many different parts of the world, both in the past and today.

Lots of people turned their attention to borrowings that reflect British colonialism in South Asia. Mark (@neuropathik) imagines a scene where you "take off your jodhpurs, put on your pyjamas, and sit on the verandah of your bungalow". You could add to this scene some chintz curtains, a baby in a cot wearing dungarees snuggled under a shawl, its mother with freshly shampooed hair wearing a pashmina and a bangle or two - all in all very cushy or even pukka, unless the peace is disturbed by a passing juggernaut (originally an image of Krishna dragged through the streets on an enormous cart). It is interesting how early many of these words entered English, eg chintz (1614), pukka (1619), cot (1634), shawl (1662), bungalow (1676), dungaree (1696). Many of the South Asian borrowings that have entered everyday British English have first dates in the OED in the 1600s, 1700s, or early 1800s, rather than in the high days of Empire - but they have been followed in the 20th and 21st Centuries by a new wave of borrowings, including names of dishes such as rogan josh (1934), pasanda (1961), or jalfrezi (1979), as South Asian culture and cuisine have made their impact in Britain and elsewhere in the post-colonial era. Today English in India, like every other variety, has its own distinctive words and uses, not all of which result just from borrowing. Deepti Ruth Azariah points out how common prepone (bring forward, ie the opposite of postpone) is in Indian English. In the future, maybe this will spread to other varieties?

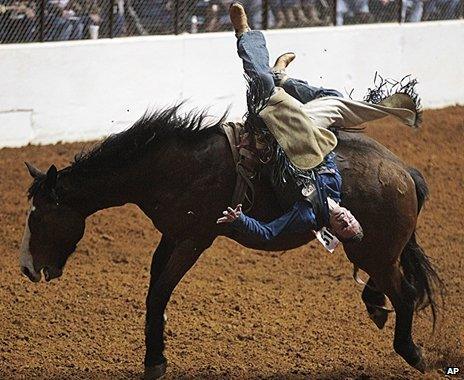

Bronco, rodeo, chaps - but longing for a lasso?

Bert Garza of Austin, Texas drew attention to some of the words of Spanish origin that still carry an unmistakable twang of the Old West, such as corral, bronco, chaps (short for chaparreras), rodeo, and lasso - to which you could add bonanza, canyon, stampede, lariat, or that standby of cowboy films vamoose (literally "Let's go!"). He points out that the Spanish influence is there in words and flavours on the high street today - you can't go a block in downtown Austin without finding tacos, fajitas, or tequila. Many of these words are now also very familiar in English in other parts of the world, but probably their pathway has been from Spanish to US English and then from the US to other "Englishes" all around the world. This sort of borrowing between varieties of English grows ever more in importance as the global spread of English continues apace.

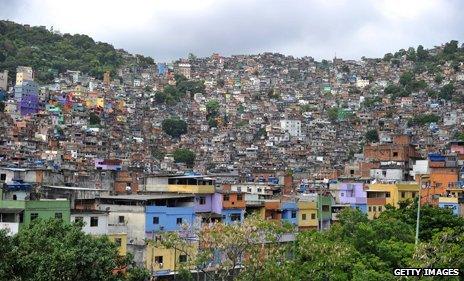

As English has come to have such a global importance, exchanges between English and other languages flourish even in places where there have never been very large numbers of first-language speakers of English. Many readers drew attention to examples from South America. Raimundo L Santos from Belo Horizonte, Brazil paints a vivid picture of how English and Portuguese continue their long give-and-take relationship. Among English words in common use in Portuguese, he notes that some show little or no change, like babysitter, delivery, self-service, show, check-up, time, shopping centre, mall, bike, drink, while others may be just a little harder for English speakers to spot in their new Portuguese forms, such as chequim, ianque, beisebol, voleibol, bangalo, coquetel, sanduiche, tenis, vagao, futebol, treiler (ie check-in, Yankee, baseball, volleyball, bungalow, cocktail, sandwich, tennis, wagon, football, trailer). American Spanish guachiman (watchman or guard) and guaya (wire) were other favourites that readers noted from elsewhere in South America.

Among borrowings in the other direction, from Portuguese to English, readers noted the ubiquitous samba, as well as favela (shanty town), caipirinha (a Brazilian cocktail), cachaca (rum-like spirit), acai (type of palm tree), and the aggressive, predatory piranha (borrowed into English in the early 1700s). Some others are mango, pagoda, monsoon (all borrowed way back in the 1580s), mongoose (1673), teak (1698), or cuspidor (1779). Sometimes it is hard to be certain whether a word has come into English from Portuguese or Spanish, for instance caste, hurricane, banana, molasses, flamingo, grandee (all borrowed in the 1500s), yam or pimento (both mid-1600s).

In very many cases, English has borrowed a word from one language that had previously borrowed it from elsewhere. Among those Portuguese and Spanish words there are many that originated among speakers of very different languages. For instance, piranha comes ultimately from Tupi (a language of Brazil) and acai comes from a related language called Nheengatu, while mango is probably ultimately from Malayalam across the other side of the world in India, and monsoon is ultimately from Arabic (and in a further twist, Dutch may also have played a hand in how it came into English from Portuguese).

Mango: From India, where it's the official the national fruit, via Portuguese

It is often useful to distinguish between immediate and remoter origins of words. For instance, among the French borrowings into English in the original article, peace comes from an earlier form of French paix which goes right back to the Latin origins of the French language (the Romans spoke about pax), but war comes from a northern variant of French guerre, a word which French originally borrowed from a Germanic relative of German and Dutch. A similar example noted by a reader is boulevard, a word that English borrowed from French in the 1760s, but that French itself borrowed in the Middle Ages from Dutch bollwerk or a related word, making the word seem more familiar by substituting the ending -ard of words like placard. In some cases English acts as the middle-man - cake probably came into English from early Scandinavian in the 1200s, but has since been borrowed from English into numerous languages in Europe and beyond.

Monsoon: From Arabic to English via Portuguese and maybe even Dutch

Prestige or even fashion can have a big impact on patterns of borrowing. Haruko Yamaguchi chuckles when she hears her English-speaking colleagues enthusing over the Japanese bento box with its separate compartments for different items, while Japanese people are now often calling the same thing a lunchbox. What it is to be cool - a word that English has spread around the world in recent decades, like OK.

A bento box to the English, a lunchbox to the Japanese

Several people pick up on the food and drink theme. These words can cast interesting light on cultural, social, and economic history. For instance, marmalade is a surprisingly early borrowing into English directly from Portuguese in the 1400s. The same borrowing is found in most other Western European languages (in modern German it's a common word for jam), but much later than in English. Its early arrival in English is probably the result of close diplomatic and trading relations between Portugal and England in the late Middle Ages. Italian bistecca (beefsteak) reflects the association of the English-speaking world with beef eating. The French go further, having been in the habit of referring to the English as the rosbifs (or "roast beefs") since at least the 1770s.

Many of you noted how borrowings can often take on quite new meanings in their new language, such as French le relooking (makeover), le self (cafeteria), Spanish el footing (jogging), German das controlling (corporate finance), or of course das handy (mobile phone).

But perhaps for an English speaker nothing can quite beat the frisson of hearing familiar words turning up in unexpected places, like French le weekend or le parking, or in German das baby or expressions like ich will doch up to date sein ("I want to be up to date"), or even ich war overdressed ("I was overdressed").

Just sometimes, though, many languages across the world will have similar words in the same meaning for reasons other than borrowing. The clearest example is probably from words for "mother" and "father" around the world that are superficially similar to mama, dada, or papa. Such words all ultimately go back to the sounds that babies throughout the world produce when they first start to master the art of producing distinct speech sounds, the familiar "mamamamama" or "dadadadadada" that few parents can help interpreting as their own special greeting, and that have given rise to many and various words for mother and father all around the world. Sometimes words of this type can be borrowed between languages, for example the early use of papa in courtly and refined circles in English makes a French origin seem reasonably probable, but it remains very hard to rule out the possibility of independent origin. For this reason we will probably never be entirely certain whether dad came into English from Welsh - just like baby mentioned in the original article.

Philip Durkin is the author of Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external