A Point of View: Should the English have a say on Scottish independence?

- Published

- comments

Should the English also have a right to decide on Scottish independence, asks Roger Scruton.

In all the complex changes leading to the Scottish bid for independence the English have never been consulted. The process has been conducted as though we had no right to an opinion in the matter. It was all about Scotland, and how to respond to Scottish nationalism.

As an Englishman I naturally ask why my interests in the matter have never been taken into account. When the Czechs and the Slovaks achieved their amicable divorce it was by mutual agreement between elected politicians. What is so different about Scotland, that it decides everything for itself?

The Union of England and Scotland was formally declared in the Act of Union of 1707. But it had been an emerging reality throughout the preceding century. In the conditions and conflicts of those days it was impossible for the two nations to regard themselves as fundamentally distinct. They shared an island, a religion, a language, and a monarch. And both had espoused the Protestant cause.

It's true there was a border between them. And things on one side of the border were not always replicated on the other. Scots law was, and remains, a separate system from the English. Styles of dress, architecture, popular entertainment and speech were for a long time quite distinct, in part because of the striking difference in climate. And, since the Reformation, organised religion has taken a very different form in the two countries, the lowland Scots opting for the Calvinist and Presbyterian version, and remaining largely hostile to the elaborate episcopal offices that appealed to the English. But the differences were less important than the history and geography that held the two nations together.

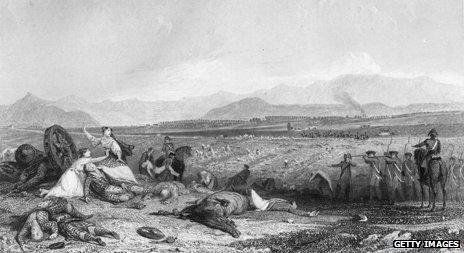

It is true that the union was resented by the highlanders, many of whom had retained their Catholic faith, their Gaelic language and their loyalty to the deposed Stuart kings. The cruel suppression of the Jacobite rebellions, the forbidding of the tartan, the persecution of Catholics and the expulsion of the crofters from their homes - all these things are well known, and don't cast credit either on the English or on the lowlanders who principally benefited from the union. Nevertheless during the years of empire building, merchants from both countries combined to reap the benefits of British naval power, and to explore the far corners of the earth in search of profit. And in their wake they brought the imperial government that they shared.

The Battle of Culloden (1746) ended the second Jacobite rising

Moreover, empire building had to be backed up by military force. The Napoleonic wars sealed the union between the Scots and the English, who happily adopted Great Britain as the name of their united country.

Neither people could have survived the wars of the 20th Century had they not fought side by side and with total commitment to the union. As a result of those wars, however, the empire was lost and an entirely new political landscape emerged from beneath the smoke. It is no longer possible for us to see the union as it was seen throughout the course of the 19th Century - as something natural and unquestionable. The enterprise that joined us has vanished, so too (we hope) have the military threats. Each nation is, for the time being at least, wrapped in its own internal problems.

It can be said the Scots are still reeling from the effect of Margaret Thatcher's radical economic policies and her introduction of the poll tax.

They are bound to ask themselves whether they have had a fair share of the prosperity that is visible nearly everywhere in the south of England. And the English tend to blame the migrations that threaten to overwhelm them on a succession of Labour governments.

By allowing mass immigration into England, and refusing to confront the European Union's commitment to the free movement of peoples, the governments of Blair and Brown seriously undermined the English sense of identity. At the same time, through the creation of a Scottish parliament, they gave a new identity to the Scots.

The effect of the Scottish Parliament, however, was not only to ensure that the Scots would govern themselves, but also to make it more likely that they would continue to govern the English. The Labour Party did not want to lose those Scottish MPs, since it was thanks to them, and to the Scottish vote, that the Labour Party had achieved such a large majority in Westminster. Scots were disproportionately represented in the cabinets of both Blair and Brown. Tony Blair was born and partly educated in Scotland, and owed his position in the Labour hierarchy in part to the networks that had grown in that country.

Elections to the Scottish Parliament show that the Scots have shifted their allegiance from Labour to the SNP. But they still want the English to be governed by the Labour Party. Hence they vote to place Labour politicians, whom they don't particularly want at home, in Westminster.

As a result of this the English, who have voted Conservative more often than Labour in post-war elections, have to accept a block vote of Labour members of parliament sent to Westminster by the Scots. The process that brought this about was one in which the Scots themselves were given the final say, in a referendum from which the English were excluded. In other words the process of devolution can be seen as a piece of gerrymandering, the effect of which has been to secure a Labour bias in the Westminster Parliament, while allowing the Scots to govern themselves in whatever way they choose.

A sitting of the Scottish Parliament at Holyrood

And the process continues. In response to Alex Salmond's bid for independence the people of Scotland have been granted another referendum. But again the people of England have been deprived of a say. Why is this? Are we part of the union or not? Or are the politicians afraid that we would vote the wrong way? And what is the wrong way? What way should we English vote, given that the present arrangement gives two votes to the Scots for every vote given to the English? Should we not vote for our independence, given that we risk being governed from a country that already regulates its own affairs, and has no clear commitment to ours?

The Scottish economy is subsidised by the English. But this does not mean that England would be better off without Scotland. You give subsidies to your dependants because you depend on them. Subsidies are also investments, which have returns in the long run that may more than justify the cost.

On the other hand, it could be that the Scottish economy has suffered from the union overall. Boswell attributes to Dr Johnson the remark that "the noblest prospect that a Scotchman ever sees, is the high road that leads him to England". Johnson's purpose was to ridicule the romantic adulation of the Scottish landscape, which was all the rage at the time, except perhaps among those who had to live there. But he touched, without intending it, on the principal cause of Scotland's economic problems, which is the loss of human capital.

Educated Scots have constantly taken Dr Johnson's high road to England, carrying with them their knowledge and their energy, and investing it outside the borders of their homeland. In just the way that the EU today is siphoning away the young middle class from Poland and the Czech Republic, so has our union served to deprive the Scots of some of the people their economy most needs.

Royal Highland Fusiliers march through Ayr, November 2013

The security that we have enjoyed in Europe since the collapse of the Soviet Union has brought with it a certain complacency in the matter of defence. During the Cold War the Scottish landmass was absolutely fundamental to our strategy. Our nuclear deterrent is housed in Scottish waters, and the Scottish airbases were constantly called upon to deter Soviet violations of our airspace. Scottish regiments are at the forefront of our campaigns today, and without them we would be much less capable of defending ourselves in a serious crisis.

In my opinion defence is the sole reason for thinking that the breakup of the union might be bad for both our countries. The union would have to be replaced by a strong and committed alliance. But I think this would happen, just as the colonial administration of America transformed itself, in time, into the Western alliance, which brings the British and the Americans together and fighting side by side in every major crisis.

Suppose then we English were finally allowed a say in the matter, which way would I vote? I have no doubt about it. I would vote for English independence, as a step towards strengthening the friendship between our countries. It was thanks to independence that the Americans were able at last to confess to their attachment to the old country, and to come to our aid in two world wars. Independence is what real friendship requires. And the same is true for those, like the Scots and the English, who live side by side.

A Point of View is broadcast on Friday on Radio 4 at 20:50 GMT and repeated on Sunday at 08:50 GMT. Or catch up on BBC iPlayer

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external