How Aborigines could solve Australia's bushfire problem

- Published

Strong winds and soaring temperatures have led to dozens of bushfires in southern Australia. Could Aboriginal "gardening" techniques be used to control them in future?

I am only an hour into visiting a retired couple just north of Sydney when I realise Bill Plant has left the room and not come back.

"Must have smelt smoke," his wife Julie suggests.

Bill's compunction is a lifetime in the making, an olfactory fire alarm he shares with many of his fellow compatriots.

"If you find fire, you phone neighbours, get buckets and go help," Bill explains upon his return.

Largely ascribed to global warming, average temperatures are increasing in Australia.

The land dries crisp and tinderbox very quickly. One careless cigarette butt, bolt of lightning, or piece of broken glass can instigate voluminous bushfires which race and rage across the land, incinerating everything in their path.

The most prolific tree in the Australian bush is the iconic eucalyptus, nicknamed the "gum tree" and described to me by one fireman as "a living firebomb".

The bark of the tree falls away in thin flammable sheets - a touch paper to any passing spark - whilst the air in and around a eucalyptus forest hangs with the oil for which the tree is renowned. It creates an incendiary haze which sometimes causes the air to burn by itself.

The Blue Mountains are a vast carpet of heritage listed forest in the state of New South Wales, so named because, from a distance, this cloud of oil gives the mountains a slate blue hue.

At the end of last year, ferocious fires here burnt 200 homes to the ground. On my way to view the damage three months on, the car radio warns of another fire alert in the neighbouring state of Victoria with the ominous words: "It is now too late to leave the area. Ready yourself."

When I arrive at Yellow Rock, the scorched valleys are a surreal sight. Heavily blackened trunks stand stubborn in the burnt dust. But sprouting from their spiky tops are iridescent explosions of green shoots.

"Everything about the eucalyptus tree is designed to catch fire, spread fire and then grow back once its competitors have been destroyed in that fire," observes Bill Gammage.

I am crouched on a heat-cracked rock overlooking a valley of burnt bush as I talk to Bill, a semi-retired history professor from the Australian National University.

"What people have forgotten is that a lot of these trees were not here when the Europeans first arrived," he asserts.

The highly flammable eucalyptus tree

As a historian, Bill examined thousands of old eyewitness testimonies, paintings and drawings and found that, before the Europeans arrived, places like the Blue Mountains once contained significant amounts of grass pasture. His book on the subject won the Prime Minister's Literary Award.

Having lived and evolved on the continent for millennia, Aborigines managed the land almost like a garden - effectively using expertly controlled fires to keep the flora in check.

The resulting grasslands not only attracted animals which the Aborigines could hunt, they also provided massive firebreaks preventing the kind of destructive fires Australia is increasingly suffering.

When the Europeans arrived they kicked the gardeners out of the garden. And the garden went wild.

The common notion, fought for by the powerful green lobby, is that eucalyptus forest is the natural state of Australia and that every tree must be protected. Hence you have to apply for a licence to chop down even one tree growing near your house.

"It is too late to reverse the clock back to 1788," says Prof Gammage. "But the kind of damage we are looking at today could be lessened if we employed Aborigines to do something they spent tens of thousands of years perfecting."

Jack Saunders, a 17-year-old New South Wales firefighter, is keen to show me his copy of the official Bushfire Fighting Manual. The chapter on fire prevention acknowledges that controlled burning may be used "to maintain the natural condition of the environment and imitate the use of fire by its traditional owners over tens of thousands of years".

But there is an odd tension here, which rather unusually pitches conservation groups against an ancient knowledge. What exactly is the "natural" environment of Australia?

Is it the massive forests which have proliferated since 1788? Or is it the Australia gardened by the Aborigines for the tens of thousands of years prior to that?

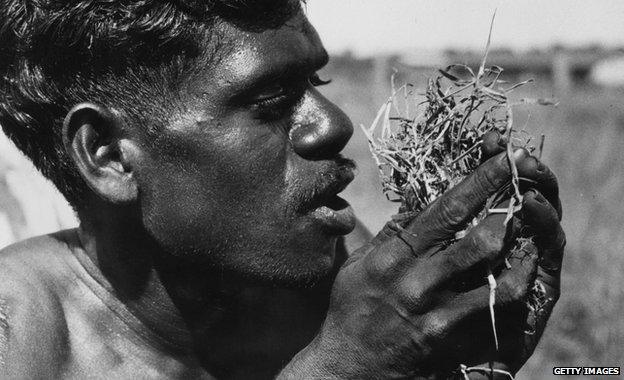

Aborigines were once the 'gardeners' of the land, expertly controlling fires

Local residents thank fire fighters for their work fighting the bushfires

A banksia bush seed pod only opens in the heat of a flame

In the burnt Blue Mountains bush I reach down to pick up the charred husk of a seed pod. It comes from the banksia shrub, the seeds of which are only released by the heat of flames.

Another timely reminder of how, along with the gum tree and the human being, Australia has evolved with, and been forged by, fire.

From Our Own Correspondent, external: Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

- Published9 February 2014