How parasites manipulate us

- Published

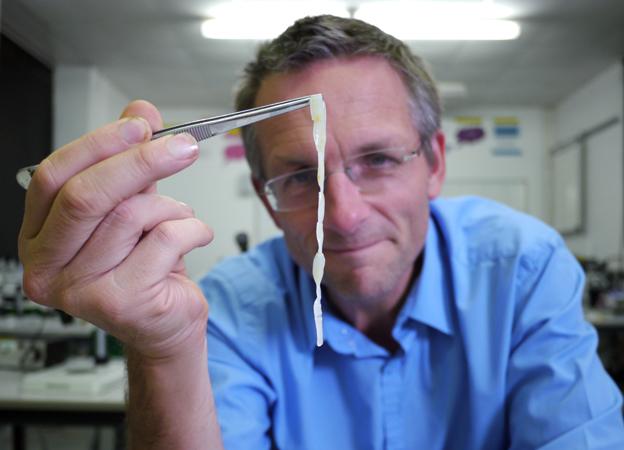

Humans infected with parasites could behave in surprising ways. Michael Mosley subjected himself to tapeworms and leeches to find out more.

Over the last couple of months I have been deliberately infecting myself with a range of parasites in an attempt to understand more about these fascinating creatures. Perhaps the greatest surprise is the extent to which parasites are able to subtly (and sometimes not so subtly) manipulate their host to their advantage.

The first parasite I experimented with was a beef tapeworm, Taenia saginata. This parasite only infects humans and cattle. In Victorian times women would, allegedly, swallow tapeworm eggs as a way of losing weight. This would almost certainly have been a waste of time as tapeworm eggs are not infectious to humans. They first have to be eaten by a cow or bull, where they form a cyst, and it is only if we eat raw, infected meat that we acquire a worm.

Even if you were infected would you lose weight? Despite hosting three worms I actually put on weight. It could be that the tapeworms were actually encouraging me to eat more, or it could be that I was unconsciously compensating for them there. Either way, they don't seem to be a great weight loss aid.

A far more lethal and dangerous parasite is Plasmodium, the parasite that causes malaria. Like all parasites it needs to find ways to spread itself, jumping from one host, the mosquito, to us and then back again. Scientists are only just beginning to understand the ways it manoeuvres us to achieve its ends.

You have probably had the experience of going on holiday with a friend and discovering that one of you gets bitten far more than the other. The reason is that while mosquitoes are attracted by the heat and carbon dioxide we produce, they can be repelled by chemicals in our body odour.

To test this idea out I went into a closed room with Dr James Logan of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Then mosquitoes were released. Over the next 15 minutes James was bitten 25 times, while I was only bitten once. It turns out that I have a body odour that is far more strongly repellent to mosquitoes than James. He said, however, that if there had been a third person in the room who had malaria then that person would have been bitten the most. New research has shown that the malaria parasite is able to alter our smell, making us more attractive to mosquitoes.

Once the mosquito has drunk blood from a human with malaria, the parasite infects the mosquito's brain, making it more likely to target another human. By manipulating mosquitoes and humans the parasite is able to spread itself extremely successfully.

However, by doing this sort of research James and his colleagues are hoping to find ways to create natural smells that might be effective at repelling mosquitoes. Since malaria kills around a million people a year and mosquitoes are becoming increasingly resistant to insecticides, new approaches are urgently needed.

An even more remarkable mind-manipulating parasite I've looked at is Toxoplasma gondii. It infects many warm-blooded mammals, but the best studied relationship is that between rodents and cats. Normally a rat or mouse will keep to the shadows, thus avoiding cats. But when they are infected by toxoplasma the parasite completely changes their behaviour. An infected mouse is attracted to the smell of cat urine and will move out into the open, displaying reckless behaviour. The reason, of course, is the parasite wants the mouse to be eaten by a cat, so it can then infect its new host.

Humans also get infected by toxoplasma, though it is only really serious when a woman is pregnant as toxoplasma can damage the unborn child. But new research suggests that toxoplasma may influence us in more subtle ways.

We know, for example, that people who have antibodies to toxoplasma are more than twice as likely to be involved in a traffic accident. It could be that the parasite is making us, like rodents, behave in a more reckless fashion. Research also suggests it may slow down reaction times, with the intention of making us more vulnerable to large predators. Either way it is a chilling thought that parasites may be influencing how we behave in ways we do not yet begin to understand.

Infested! Living With Parasites is broadcast on Wednesday 19 February, BBC Four, 21:00 GMT. Or catch up with iPlayer.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external