Life after Guantanamo prison

- Published

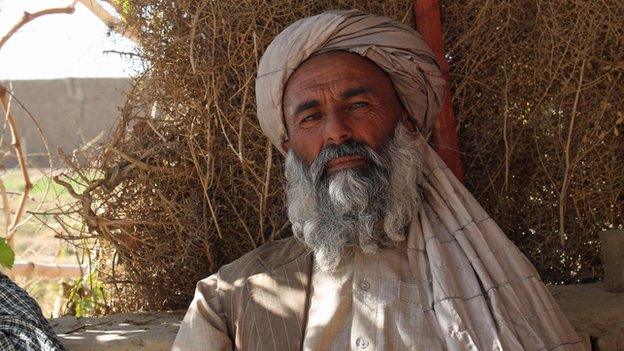

Haji Shahzada Khan spent two years at Guantanamo

Some 220 Afghans have been held at the US military prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, making them the largest single group of the nearly 50 nationalities involved. The vast majority have returned home, where their stories of imprisonment, and sometimes abuse at American hands, have made a big impact.

I stopped strangers on the street in Kabul and other provinces of Afghanistan to ask if they had heard of Manhattan or the World Trade Centre. Few of them had. But all of them knew about Guantanamo.

"In the history of mankind, there have been only two such cruel prisons. One was Hitler's and the other one is this American prison," says Haji Ghalib, a former district police officer from eastern Afghanistan, who was arrested in his office in February 2003.

That sums up the reputation Guantanamo has in Afghanistan.

Three Afghans died in detention. Of the rest, all but 19 have been freed without charge, and have usually returned home to a hero's welcome.

Izatullah Nasratyar received a warm welcome returning to Afghanistan

"Thousands of people from my villages and the surrounding area had gathered to welcome me. I shook hands with more than 2,000 of them," says Haji Shahzada Khan, a village elder from Kandahar, southern Afghanistan.

It was much the same for Izatullah Nasratyar, a former Mujahideen fighter who helped push Soviet troops out of Afghanistan, with American help, in his youth.

"People gave me a very warm welcome. They brought me cattle and other things they could afford," he says.

But how much the ex-detainees are prepared to say about their experiences varies.

Some have written books that have become bestsellers in Afghanistan and Pakistan, external. Others are more guarded.

"They did things to us that is against humanity, against human rights and against Islam. I cannot even talk about that and I will not talk about it," says Haji Nasrat Khan, Izatullah's elderly father.

He was already in his late 70s and in poor health when he was seized in 2003 by the US forces in a raid at his house in a village a few kilometres outside the Afghan capital, Kabul.

"I told them find me a single bit of evidence. If you don't have the evidence, then why have you arrested me and kept me here? It was not only me, there were a lot of innocent people they detained."

Haji Shahzada also prefers to remain silent.

There are believed to be around 155 prisoners in Guantanamo currently

"I usually say to people that Guantanamo is like the mother-in-laws' home. That it's a nice place," he says.

"If we tell the truth about conditions there, then it will increase the worry and the suffering of the relatives of remaining detainees. I cannot disclose the realities of life in Guantanamo."

The experience of Guantanamo is different for different prisoners.

So-called "compliant" detainees - those who follow the rules - live together in a communal way, can meet other inmates from their own block and are able to learn as well as read.

"People there don't waste their time. The only good memory I have from Guantanamo is that I learnt the Koran and writing and also got a different experience," says Haji Ghalib.

"I memorised the Koran there and learnt many new prayers that now I recite regularly," says Izatullah Nasratyar.

Both men spent four and a half years at the detention facility.

But Haji Ruhullah, a tribal elder from eastern Afghanistan, paints a harsher picture.

"Guantanamo not only took the freedom of movement, it also took all the other rights. Even talking was not allowed," he says. "We were not even allowed to move our lips while reading a book or reciting the Koran. The guards would punish us because they thought we were talking to other prisoners."

Nearly all the former inmates I spoke to said they did not expect to return back alive. Many compared the experience of Guantanamo with death - and their release to being reborn.

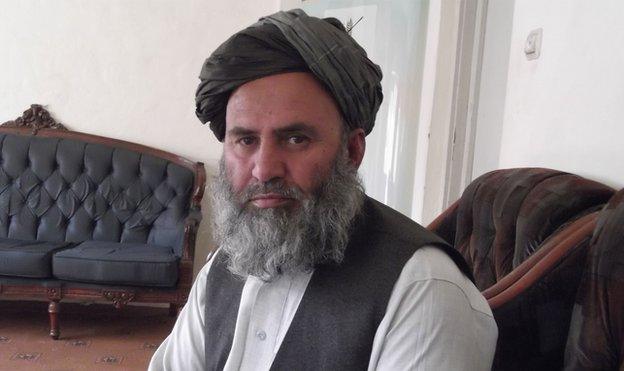

Mawlawi Abdul Razaq spent four years at Guantanamo

"When we were transferred [to Afghanistan] from Guantanamo, it was like rising from the dead," says former Taliban government Minister of Commerce, Mawlawi Abdul Razaq, who spent five years in detention after his arrest in April 2002, four of them in Guantanamo.

"While in Guantanamo, we didn't have any knowledge of the outside world. The letters we were exchanging with our families were mostly censored and blacked out by the Americans. We were worried about our families… The difference was like coming out of the grave."

Izatullah says the experience of Guantanamo changed his outlook on life.

"This prison has given me a lot of good things," he says, surprisingly.

"I was never thankful enough for the bounties Allah has bestowed upon us. I had not thanked God for the freedom to be in the sun or the shade at your own free will or to go to the toilet whenever you want to.

"But when we were in the hands of other men we realised that God has bestowed a lot of bounties upon us. It was only then we realised what a privilege freedom is."

After the joy of homecoming, though, the experience of picking up after four or five lost years has often been bitter.

"I went to see my vineyards after my release and found out that up to 5,000 of the vine trees had dried up. That is the memory that haunts me the most," says Shahzada Khan.

"My small children couldn't look after them in my absence. That was the day when I realised that I had really been imprisoned."

People have been protesting for the closure of Guantanamo for years

Some of the former detainees lost their livelihoods and jobs.

"Neither the government nor anyone else will employ us - I've been without a job since I came home. Even after we were proven innocent, why won't they help us?" says Haji Ghalib, the former district police officer.

Although released without charge, many of them say they are still harassed by the US and Afghan security forces, who suspect some of them of possible links with the insurgents.

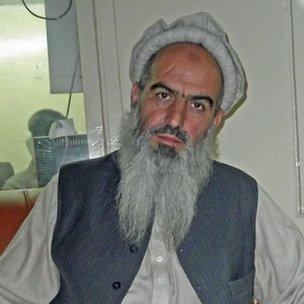

Haji Ruhullah Wakil heads a support group

A few former detainees have been killed in raids, mostly by US forces. Some have been re-arrested and imprisoned in Afghanistan, accused of being "involved in subversive activities".

In fear of such a fate, about 90 of them came together in 2012 to form "The Association of Former Guantanamo Detainees from Afghanistan".

"We came together in this body to support each other and protect our rights," says Haji Ruhullah Wakil, the head of the association.

"We have met President Karzai, Nato commanders and the US officials in Kabul to discuss our problems and assure them that we pose no threat."

The mere existence of Guantanamo, however, does continue to pose a threat - as the Taliban is able to exploit the fact in verse designed to recruit and motivate fighters.

One such chant describes a young Taliban detainee writing a letter to his mother.

"I am a prisoner in Cuba's jail // Neither at night, nor at day, I can't sleep, oh mother," it goes.

The singer describes the hardship of life at Guantanamo and tells his mother there is no hope of seeing him alive.

The Americans have to weigh this danger against the risk of releasing potentially dangerous men.

The detention facility still holds 155 detainees - down from a peak of nearly 800.

"The detainees that were brought here were picked up on the battlefield. We kept them here to keep them off the battlefield," says Admiral Richard Butler, commander of the Joint Task Force, that runs the Guantanamo military prison.

"Once the chain of command decides they're no longer needed to be kept here for that reason, then we'll transfer 'em. But until then I make no judgement on the guilt or innocence of the detainees."

Haji Ghalib did return to Afghanistan, and was reunited with his family. But without a job, living in a cold damp apartment in Kabul, his life has undergone a radical turn for the worse.

"Two Americans told me that our American government apologises from you because you spent five years here but you were proven innocent," he says.

"I told them, 'I cannot forgive you from my heart.'"

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external