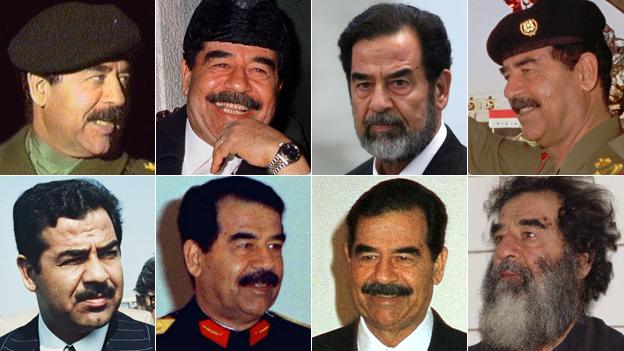

The perils of sharing a name with Saddam Hussein

- Published

It has been a decade since the former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein was captured, but those unfortunate to share a name with the infamous dictator are regularly reminded of his legacy.

Having driven for a couple of hours, we were finally stopped on the way into Aziziyah, south-east of Baghdad.

A policeman wanted to know what we, a team of journalists from a foreign news organisation, were doing in his small town.

As he looked over our papers, another man, wearing a full-length black robe and leather jacket, emerged from a car nearby.

"They are here to see me," the man said.

"And who are you?" the policeman asked.

"I am Saddam Hussein," he replied.

I know what you are thinking. What was Saddam Hussein even doing alive, much less introducing himself in a mostly Shia town?

Was he not executed in 2006, after ruling Iraq with an iron fist for nearly a quarter of a century, heading a Sunni Arab regime responsible for the deaths of hundreds of thousands, including countless Shia?

But this was another Saddam. One who, like countless men, both Sunni and Shia across the country, has been cursed with a name that was originally given in tribute to a vice-president on the way up, but which has since become associated with a brutal dictator.

Saddam Hussein Ulaiwi, the man I met, is a 35-year-old Shia man who ekes out a meagre living as a neighbourhood generator operator. He was friendly and generous, offering us a hearty lunch as we sat and talked about what his life has been like as the namesake of the former president.

He was named by his grandfather in 1978 when Saddam was not yet president but was on the rise and increasingly admired. But the name quickly became something of an albatross around his neck.

School teachers held him to impossible standards, expecting the young Saddam Hussein to replicate his namesake's apparent successes. They punished him severely when he failed to meet them.

As a conscript reporting to join the army, he had expected that, at least in the military, soldiers and officers would be kinder to him, but in fact it was the opposite.

When he first reported to pick up his uniform, the officer on duty violently assaulted him when he declared his name, angrily accusing him of desecrating the president's name by daring to compare himself to him.

Saddam Hussein was executed by hanging in Iraq in December 2006

After Saddam the dictator was ousted in 2003, Saddam the generator operator had hoped he would be freed of the baggage associated with the name, but, as with many things in post-invasion Iraq, the reality was more complex.

Political parties called his father and asked him to change his son's name, but the family declined. People still berate him on the street. Civil servants at government offices often refuse to deal with his requests.

Things got so bad that he even tried to change his name in 2006, but was put off by the length of time required to deal with Iraq's famously Byzantine bureaucracy and the relatively large expense for someone of modest means.

Other Saddam Husseins, from the mostly Sunni north and west down through the Shia south, told me of a wide variety of tribulations of their own.

One Saddam, a journalist working in Ramadi, a Sunni city in the desert province of Anbar, said his father was fired from his government job because he could not convince his superiors he was not a member of the dictator's Ba'ath party.

He had named his son Saddam, after all - what greater allegiance could he have shown to the ousted president, they argued.

Others had more terrifying stories - one said he was captured by a Shia militia, set down on his knees and had the barrel of a gun placed against the back of his head. Somehow, thanks to sheer luck, the weapon jammed, and the militia eventually released him.

One friend told me how, as a Kurdish schoolchild in Baghdad, he had known a fellow classmate named Saddam Hussein.

While playing football with the boy, they would often shout at him: "It is not only us who hate you, the entire country hates you."

It has now been a decade since Saddam was captured, his regime replaced, and the public tributes to his rule taken down - there are no more statues, posters or landmarks honouring him.

But there are these men. They are now among the few remaining reminders of the dictator.

I asked Saddam the generator operator how he responded to people who shout at him on the street, angrily berating him for his name.

"I only have the name," he said, sitting with his father in their modest one-storey family home.

'"It is only a name," he said, almost pleading. "It means nothing."

Prashant Rao is the Iraq Bureau Chief for AFP.

From Our Own Correspondent, external: Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external