Electric chair haunts US former executions chief

- Published

The US executioner who wants the death penalty abolished

Warning: This article reports a racist term in the section headed Racial intimidation.

Most guests come into the HARDtalk studio with their guard up, their defences prepared. Dr Allen Ault simply faced the cameras and bared his soul.

His account of supervising executions in the US state of Georgia was one of the most painful, searingly honest and courageous testimonies I have ever heard.

Dr Ault is a soft-spoken Midwesterner with steel-grey hair and a steady gaze.

As he spoke about his years as corrections commissioner for the US state of Georgia, he appeared to forget the artifice of the TV studio and relive his experiences in the execution chamber.

"I still have nightmares," he told me.

"It's the most premeditated form of murder you can possibly imagine and it stays in your psyche for ever."

"Murder" - an extraordinary word to come from the lips of a man who administered America's ultimate punishment on five occasions.

What happened to Allen Ault? What turned him from a loyal servant of the judicial system to a passionate campaigner against capital punishment?

His painful journey began with a promotion. Dr Ault was a psychologist who worked in the diagnostic and classification centre of the Georgia prison service.

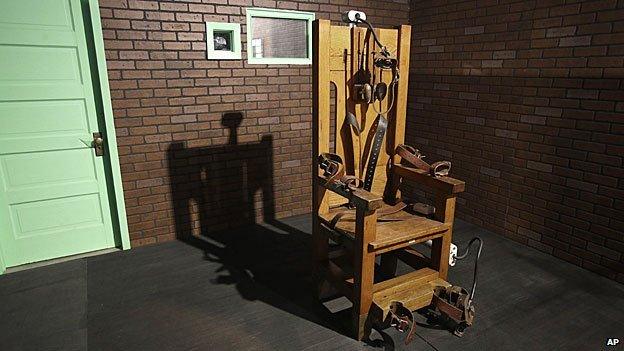

Georgia ceased using the electric chair after 1998 and now uses lethal injection

The centre was chosen to house Georgia's execution chamber and Dr Ault became its warden. Without ever closely examining his own feelings about the death penalty, he found himself in charge of the machinery of death.

In Georgia's case, it was the electric chair. Mr Ault remembers every detail of every execution he oversaw.

Perhaps the most troubling was that of Christopher Burger, who as a 17-year-old juvenile with borderline mental impairment had been involved in a brutal rape and murder.

Burger spent 17 years on death row. Dr Ault saw him change. The troubled youth got an education, his brain developed and matured.

Yes, he was guilty of a terrible crime. He was also desperately contrite.

When Dr Ault described Burger's execution to me, his words were powerful, the agonised silences even more so. Two decades have done little to ease Dr Ault's burden of remorse and guilt.

"His last words to me were, 'Please forgive me'.

"I could see the jolt of electricity running through his body. It snapped his head back and then there was just total silence... and I knew I had killed another human being."

Racial intimidation

Each execution that Dr Ault supervised deepened his misgivings.

William Henry Hance was a black man convicted, by a majority white jury, of murdering three women.

One black member of the jury later described an atmosphere of racial intimidation. A white juror had said execution would leave "one less nigger to breed".

Hance's IQ was so low that some experts believed he was not competent to file a plea. Nonetheless, he was convicted and it fell to Allen Ault to supervise his electrocution.

"Why didn't you walk away?" I asked Dr Ault on HARDtalk. "Eventually I did," he breathed.

"But it was too late?"

"Yes… And I've spent a lifetime regretting every moment and every killing."

Dr Ault left his post as Georgia's corrections chief in 1995. In the years since, he has received counselling to try to come to terms with his overwhelming sense of guilt.

He has also become a high-profile campaigner against America's use of the death penalty. He rejects the idea that the prospect of execution has any significant deterrent effect.

And there's the racial element to the application of the ultimate punishment.

"Kill somebody white and you're three times more likely to get the death penalty than if you kill a black person," he says.

There is now a small cadre of former death row wardens and corrections chiefs who have joined Dr Ault's campaign against the death penalty.

And their message is striking a chord.

Some 28 US states have declared their opposition to capital punishment, and the number of executions has fallen.

But opinion polls show a majority of Americans still believe in the utility and justice of killing those convicted of the most heinous crimes.

So Allen Ault continues to bare his soul to change his country's mind.

"No-one has the right to ask a public servant to take on a life-long sentence of nagging doubt, shame and guilt," he concludes.

This is not a rhetorical point. He's talking about himself.

HARDtalk is broadcast in the UK on BBC Two and the BBC News Channel and around the world on BBC World News. In the UK you can catch up on past programmes on BBC iPlayer including the full interview with Allen Ault.