The lost era of the A-Z map?

- Published

A new musical celebrates the woman credited with popularising A-Z city map books. The digital revolution may have threatened to kill off paper-based cartography, but could the street map ever be in for a revival?

They sit neglected on shelves and in glove compartments - dog-eared, daubed with scribbled notes, with train tickets serving as improvised bookmarks.

Once a city street index was commonly in the pocket or bag of urban-dwellers before they ventured outdoors. Keys, wallet, street map was the pre-exit routine. Now the age of the smartphone has seen printed maps usurped by GPS and other high-tech navigation systems.

The A-Z - the best known of a number of competing maps - was always more than just a tool for negotiating cities and towns. Each was a physical reminder of journeys and day trips - pages falling open at much-visited locations, memories of expeditions marked out in pencil and highlighter ink.

UK sales of paper maps slumped by 25% between 2005 and 2012, according to the Ordnance Survey, but it's not just wistfulness that provokes a twinge of nostalgia for the format. Any city-dweller who has ever been stranded because they ran out of batteries or couldn't get a 3G signal has had cause to regret leaving the era of printed cartography behind.

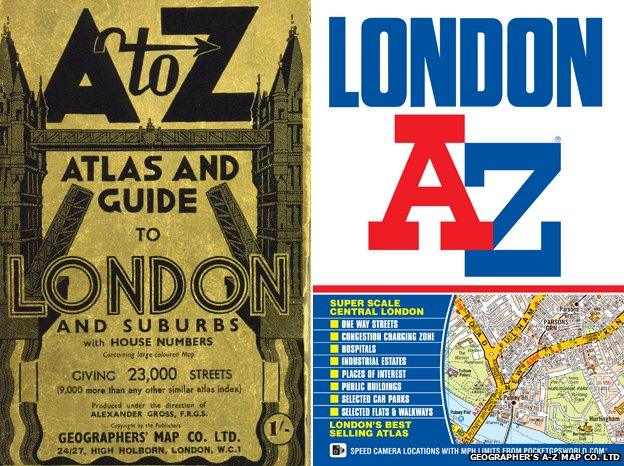

London A-Z in 1936, and in 2014

In the wake of much-publicised glitches involving Apple Maps and oft-expressed privacy concerns about the march of Google's equivalent,, external it wouldn't be surprising if city travellers yearned for the traditional version.

"Since the 1930s the A-Z has not only helped city dwellers navigate their way, but it's also imprinted a unique visual image in the brains of its users," says Simon Garfield, author of On The Map: Why The World Looks The Way It Does.

Now a musical celebrates the woman widely regarded as the street map's patron saint. The A-Z of Mrs P, starring Peep Show actor Isy Suttie, at the Southwark Playhouse, tells the story of Phyllis Pearsall, a bohemian painter who published a hugely popular London A-Z and founded the Geographer's A-Z Map Company, which produces maps of British cities to this day.

Isy Suttie in rehearsals for The A-Z of Mrs P

According to one biography, Pearsall was inspired to design a handy guide to the capital's streets after getting lost on her way to a party in Belgravia in 1935 because her Ordnance Survey map was 16 years out of date.

Popular myth records that she spent a year walking 3,000 miles to map the city's 23,000 streets. Pearsall said she would rise at 05:00 and tramp the pavements for 18 hours a day. The result was the A-Z Atlas and Guide to London and Suburbs which proved an instant success.

Much of this tale is "bunk", believes Peter Barber, head of map collections at the British Library. He is sceptical about the notion that Pearsall spent her days trudging outdoors given that all she would have had to do was ask London's local authorities for their street plans. Her father Alexander Gross was a map-maker who had drawn up a very similar A-Z.

However, admirers of Pearsall say her self-made myth nonetheless spoke of an underlying truth. "She was an artist and a storyteller," says Diane Samuels, who wrote the book for The A-Z of Mrs P. "It's a metaphor, too - on some level, if you're going through the records you are walking the streets."

Phyllis Pearsall as a young woman, and later in life

The first edition's success came despite the fact Trafalgar Square was missing from its index, as Pearsall had knocked a shoebox full of file cards marked "T" out of her High Holborn office window and not all were recovered.

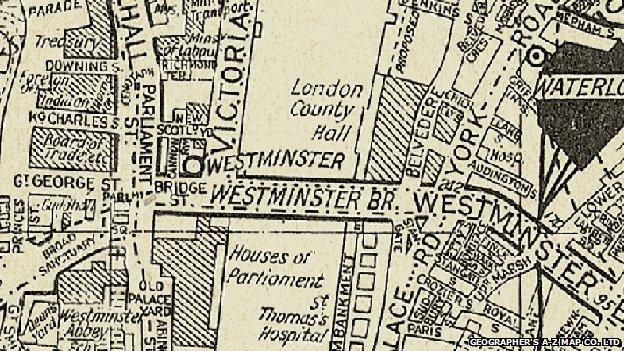

Her A-Z was not the first British street map - the Bartholomew's Reference Atlas of London and Suburbs was available from the 1910s. And streets had been mapped in reference directories for centuries. John Norden produced the first street guide of London in 1593. But something about the A-Z's visual style made it successful.

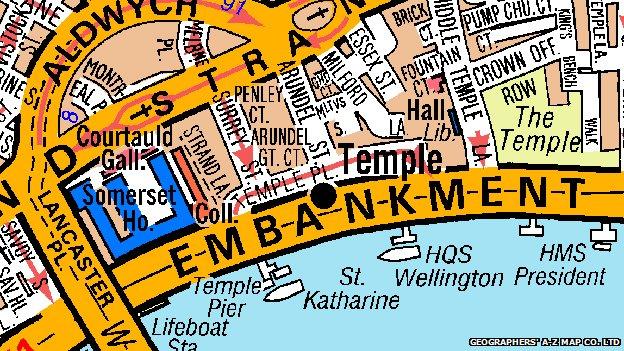

Perhaps her creation's greatest significance was its much-imitated visual language, with its wide streets, clean lines and san serif fonts.

Like all maps, the format is very obviously a product of the period in which it was created - in this case, a time of rapid urbanisation. While guides from earlier eras would have given pride of place to churches or other grand buildings, the modernist-era A-Z was brutalist in its simplicity. What mattered was the roads, and all other landmarks were secondary.

Though early A-Zs were black and white, the eventual, striking colour scheme - orange for A-roads, yellow for B-roads - helped shape the vocabulary of London taxi drivers, who as a result refer to them as "oranges" and "lemons".

"It's a design classic because it's taking what is a very complex area and rendering it very simply," says Peter Jones, president of the British Cartographic Society.

A 1936 A-Z map of London, before the introduction of colour

As time passed, the A-Z charted the changing shape of British cities. Comparing how maps over time have charted Salford in Greater Manchester or London's Docklands offers the reader a stark illustration of social as well as purely geographic transformation.

By the 21st Century the A-Z was recognised as an icon in its own right. In 2006 a survey of the nation's favourite British designs conducted by the BBC's Culture Show and the Design Museum put it in a pantheon alongside the Routemaster bus and the red telephone box. Like Harry Beck's Tube map, its instantly recognisable aesthetic has made it a template for artists., external

None of this was enough to forestall the arrival of the web.

In the interregnum between the internet reaching most offices and the arrival of the smartphone, it was common to see employees printing off street maps from the workplace printer before heading out on the town. Handheld devices made carrying a paperback book around everywhere even less appealing.

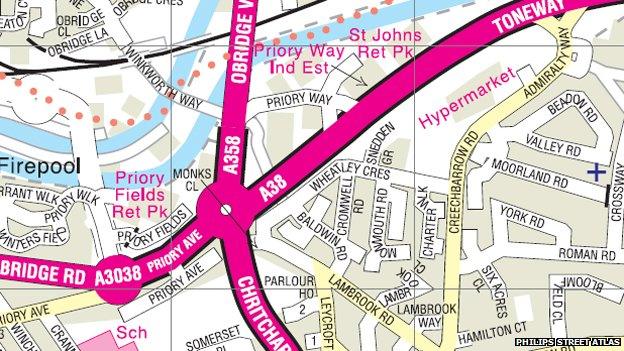

Like other street atlas brands, The Geographers' A-Z Map Company had "a couple of very difficult years", says managing director Steve Berger. But it and rivals like the Philip's Street Atlas are still going.

Following a period of restructuring, the company founded by Pearsall - which still displays her watercolour paintings on its Kent head office walls - is in profit again, he adds. While the digital side of the business, including phone apps and satnav, has driven much of this growth, the number of road maps sold by the company rose in 2013 too, he says.

Detail from a recent Philips Street Atlas map of Taunton - with colour-coded streets

The defenders of paper maps note that they are immune to the 3G black holes that afflict some cities. "When there's something like a Tube strike you sell more - people are above ground, they are walking streets they don't know," Berger says.

Looking at a screen is good for zooming in and out but a book gives you the bigger picture, suggests Jones.

"People have been predicting the death of the map on paper for some time but it has proved to be remarkably resilient."

Perhaps it's worth keeping that much-thumbed copy on the shelf a little longer.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external