How did the pro-paedophile group PIE exist openly for 10 years?

- Published

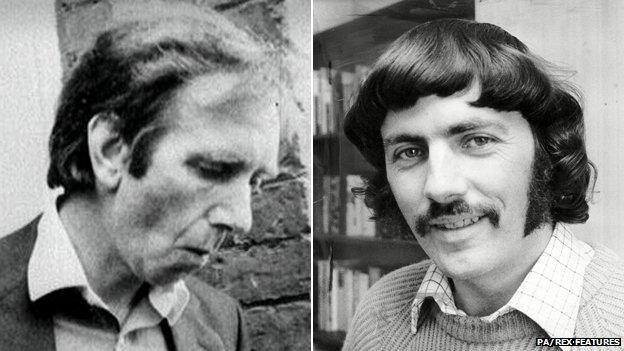

Former KGB spy and PIE member Geoffrey Prime (left) and PIE Chairman Tom O'Carroll

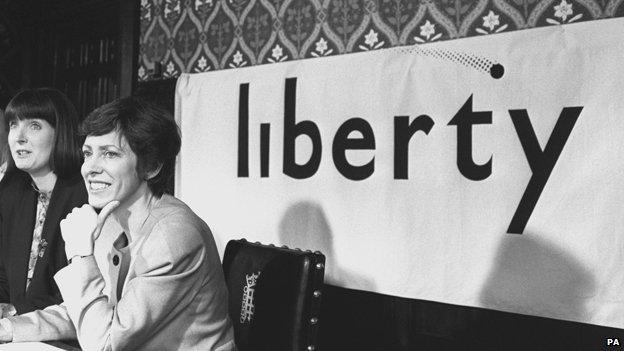

The Paedophile Information Exchange was affiliated to the National Council for Civil Liberties - now Liberty - in the late 1970s and early 1980s. But how did pro-paedophile campaigners operate so openly?

A gay rights conference backs a motion in favour of paedophilia. The story is written up by a national newspaper as "Child-lovers win fight for role in Gay Lib".

It sounds like a nightmarish plotline from dystopian fiction. But this happened in the UK. The conference took place in Sheffield and the newspaper was the Guardian. The year was 1975.

It's part of the story of how paedophiles tried to go mainstream in the 1970s. The group behind the attempt - the Paedophile Information Exchange - is back in the news because of a series of stories run by the Daily Mail about Labour deputy leader Harriet Harman.

The Daily Mail has revisited the story of PIE to ask how much Harman and her husband the MP Jack Dromey knew about the group during their time working at the National Council for Civil Liberties, now Liberty, in the late 1970s. PIE was affiliated to the NCCL from the late 1970s to early 1980s.

Many of the revelations are not in fact new. The story's return to the front pages demonstrates the shock people feel about how a group with "paedophile" in its name could operate so openly for so long.

PIE was formed in 1974. It campaigned for "children's sexuality". It wanted the government to axe or lower the age of consent. It offered support to adults "in legal difficulties concerning sexual acts with consenting 'under age' partners". The real aim was to normalise sex with children.

Journalist Christian Wolmar remembers their tactics. "They didn't emphasise that this was 50-year-old men wanting to have sex with five-year-olds. They presented it as the sexual liberation of children, that children should have the right to sex," he says.

John Tusa interviews two members of the Paedophile Information Exchange on Newsnight in 1983

It's an ideology that seems chilling now. But PIE managed to gain support from some professional bodies and progressive groups. It received invitations from student unions, won sympathetic media coverage and found academics willing to push its message.

It's wrong to say that PIE was tolerated during the 1970s, says Times columnist Matthew Parris. "I remember a lot of indignation about it [PIE]. It was considered outrageous."

The group's visits to universities were often opposed. In 1977 PIE's chairman Tom O'Carroll was ejected from a conference on "love and attraction" at University College, Swansea after lecturers "threatened not to deliver their papers if Mr O'Carroll stayed", the Times reported. The May 1978 issue of Magpie, PIE's in-house newspaper, records how O'Carroll had been invited to address students at Liverpool and Oxford University but that the visits were cancelled after local opposition.

Protestors and police outside Conway Hall, London, where PIE was holding its first open meeting in 1977

One of PIE's key tactics was to try to conflate its cause with gay rights. On at least two occasions the Campaign for Homosexual Equality conference passed motions in PIE's favour.

Most gay people were horrified by any conflation of homosexuality and a sexual interest in children, says Parris. But PIE used the idea of sexual liberation to win over more radical elements. "If there was anything with the word 'liberation' in the name you were automatically in favour of it if you were young and cool in the 1970s. It seemed like PIE had slipped through the net."

Some have suggested that the nature of the debate was different then. "In this free-for-all anything and everything was open for discussion," said Canon Angela Tilby on Radio 4's Thought for the Day. "There were those who claimed that sexual relationships between adults and children could be harmless." Homosexuality had only been decriminalised in 1967. There was still prejudice and inequality. The age of consent was 16 for heterosexuals but 21 for homosexual men.

Wolmar had first-hand contact with PIE. In 1976 he began working for Release, an agency helping people with drug and legal problems. Its office at 1 Elgin Avenue in London was a mailing address for PIE. Nobody knew much about them, Wolmar says. "They used to drop in once a week to pick up their mail. They were greasy men," he recalls, people who fitted the stereotype of the "dirty mac" brigade. After Wolmar raised questions about PIE it was decided to bring them in for a meeting.

Wolmar's colleagues pressed the man from PIE on the age of consent. Wolmar says that the man said there should be no age of consent. Shocked at the idea of a group advocating sex with babies, he and his colleagues unanimously decided to "boot them out".

It was easy to join PIE. According to a Times legal report on a blackmail case from February 1977, there was no need for subterfuge, just an application and a cheque for £4. In the report, the prosecutor in the case stated: "He said on the form that he was a paedophile, male, married, 29 years old and attracted to girls between the ages of seven and 13 years." The judge proclaimed himself "horrified" at the existence of PIE.

Unsettlingly for a modern audience, the PIE member received anonymity (as is typical in blackmail cases) and there is no mention of any prosecution of him. Meanwhile, the blackmailer was jailed for three years.

The brazenness could be shocking. Keith Hose, one of PIE's leaders during the 1970s, was quoted by a newspaper saying: "I am a paedophile. I am attracted to boys from about 10, 11, and 12 years of age. I may have had sexual relations with children, but it would be unwise to say."

When Polly Toynbee interviewed O'Carroll and Hose in the Guardian in September 1977 she heard men incredulous at the lack of support from the press. They seemed genuinely aggrieved at what they called a "Fleet Street conspiracy". One of them told her: "We would expect the Guardian, a decent liberal newspaper to support us."

Labour politicians Harriet Harman and Patricia Hewitt have come under fire for the NCCL's links to PIE

In a Guardian piece from 1975 it's clear "paedophile" was still not a widely used term and the opening line explains it - "one who is sexually attracted to children". In the piece, Hose is treated as a reliable source throughout.

There were divisions within progressive circles. In 1977 the Campaign for Homosexual Equality passed by a large majority a resolution condemning "the harassment of the Paedophile Information Exchange by the press".

When Peter Hain, then president of the Young Liberals, described paedophilia as "a wholly undesirable abnormality", a fellow activist hit back. "It is sad that Peter has joined the hang 'em and flog 'em brigade. His views are not the views of most Young Liberals."

And when a columnist supported Hain in the Guardian he was inundated with mail from people - many willing to give their name - who defended sex with children.

Reading the newspapers of the time there is a palpable anxiety that PIE was succeeding.

A Guardian article in 1977 noted with dismay how the group was growing. By its second birthday in October 1976, it had 200 members. There was a London group, a Middlesex group being planned, and with regional branches to follow. The article speaks of PIE's hopes to widen the membership to include women and heterosexual men.

Toynbee talked of her "disgust, aversion and anger" at the group but added that she had "a sinking feeling that in another five years or so, their aims would eventually be incorporated into the general liberal credo, and we would all find them acceptable".

There was a battle raging over free speech.

Some, such as philosopher Roger Scruton, felt that freedom of speech had to be sacrificed when it came to groups like PIE. In a Times piece in September 1983 he wrote: "Paedophiles must be prevented from 'coming out'. Every attempt to display their vice as a legitimate 'alternative' to conventional morality must be, not refuted, but silenced."

A Times letter writer, Peter Cadogan, took a different line, defending PIE from the National Front despite loathing them. "Yet again, they assaulted me with stink bombs and sundry soft fruit when I was defending the freedom of speech of another group I abhorred, viz, the Paedophile Information Exchange." He continues that the way to cover "nasty people with nasty ideas" is to "give them all the rope they want and then hang them with it every time they practice what they preach".

But during the 1980s, PIE came a cropper. Its notoriety grew in 1982 with the trial of Geoffrey Prime, who was both a KGB spy and a member of PIE. He was jailed for 32 years, external for passing on secrets from his job at GCHQ to the Soviet Union, and for a series of sex attacks on young girls.

A short article from the Daily Mail in June 1983 records how a scoutmaster in Castle Bromwich, Birmingham, resigned after being exposed as a member of PIE.

PIE critics: Head teacher Charles Oxley, who infiltrated PIE, Mary Whitehouse and Geoffrey Dickens MP

In August 1983 a Scottish headmaster, Charles Oxley, handed over a dossier about PIE to Scotland Yard after infiltrating the group, the Glasgow Herald wrote, external. He said the group had about 1,000 members.

But the NCCL continued to defend having PIE as a member. As late as September 1983, an NCCL officer was quoted in the Daily Mail saying the group was campaigning to lower the age of consent to 14. "An offiliate [sic] group like the Paedophile Information Exchange would agree with our policy. That does not mean it's a mutual thing and we have to agree with theirs."

The authorities debated ways of shutting PIE down. O'Carroll was sentenced to two years in jail for "conspiracy to corrupt public morals" and PIE was disbanded in 1984.

It's hard now to believe the group existed for more than a decade. "Even then the word paedophile was pretty taboo," says Wolmar. "I do find it slightly astounding that they were able to use that name."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external