Were the Vikings really so bloodthirsty?

- Published

The Viking story has fascinated people for centuries. But as a major exhibition opens at the British Museum, have people got them all wrong?

The longships arrived on 8 June. The monks at Lindisfarne didn't know it then - the year was 793 - but it was the beginning of 300 years of bloody Viking raids on Britain and Ireland.

"Never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race," Alcuin of York wrote at the time. "The heathens poured out the blood of saints around the altar, and trampled on the bodies of saints in the temple of God, like dung in the streets."

Over 12 centuries later and the Vikings are the subject of a major exhibition at the British Museum - and they still loom large in the imagination. Blond, powerfully built men with horned helmets, nostrils flaring with naked aggression, descending on settlements to rape and pillage.

That at least is the perception. But long-held views are being challenged.

Let's start with the helmets, so beloved of Scandinavian football fans. The Vikings never wore them. They have only been included in depictions since the 19th Century. Wagner celebrated Norse legend in his opera Die Walkure (The Valkyrie) and horned helmets were created as props for the performance of his Ring Cycle at the first Bayreuth Festival in 1876.

The horned helmet is based on historical fact, says Emma Boast from the Jorvik Centre, but it just wasn't a Viking thing. The British Museum has a ceremonial horned helmet, external from the Iron Age that was found in the River Thames. It is dated 150-50 BC.

The Vikings used horns in feasting for drinking and blew into them for communicating. They were depicted in Viking brooches and pendants. They weren't worn. And for battle it would have been a major encumbrance, adding weight to the helmet.

But today a child asked to draw a Viking will start with the horned helmet, Boast says. "I can understand that kids are drawn to that. It's so embedded with our society that I don't think we'll ever get rid of that. But actually there's a richer explanation."

With the new exhibition there has been soul-searching in the media. A recent New Statesman headline asked, external: "The Vikings invented soap operas and pioneered globalisation - so why do we depict them as brutes?"

A Daily Telegraph reviewer - brought up on the idea of them as "all hirsute jowls and beady eyes bent on rape and pillage" - suspects that the new British Museum will be an exercise in academic debunking, external. "I will learn that these rapacious raiders were in fact vegetarians, that they maintained some of the leading universities of the day and, worst of all, that they did not wear horned helmets."

His tongue-in-cheek fears show that the British Museum has a difficult job on its hands. "The debate about whether the Vikings were cuddly or not has been going for a long time," says Matthew Townend, who teaches Old Norse at the University of York.

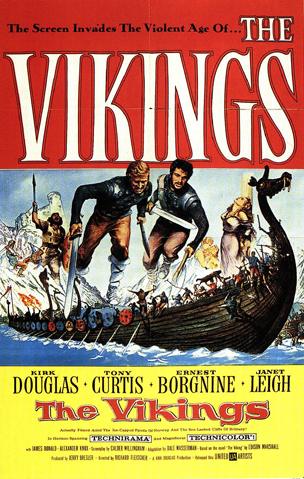

The classic view is that articulated in Hollywood's 1958 movie The Vikings. Starring Kirk Douglas, Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis, it opened with what one critic today describes as, external a "full-blooded depiction of rape, fire and pillage". At least there were no horns in evidence.

In the 1960s and 70s their portrayal as marauding barbarians was questioned. Academics pointed out that most of the written records for the Viking invasion of England were written by monks who, as the "victims", would not have been objective. Archaeology began to replace the Norse sagas - written several centuries later - as the most reliable evidence.

A crucial turning point came in the late 1970s. During the construction of a shopping centre in the Coppergate area of York, Viking homes, clothes, jewellery, and a helmet were found well preserved in the moist earth. It led to the creation of the city's Jorvik Centre. The Vikings became seen as domestic, family-oriented people.

"Until Coppergate our view of the Vikings was skewed," says Chris Tuckley, head of interpretation at the Jorvik Centre. The Viking makeover saw them transformed from bloodcurdling raiders into resourceful traders. A British Museum exhibition in 1980 - the last before this week's opening - reflected this view. They were poets. They wore leather shoes and combed their hair.

On a trip to Dublin in 2007, Danish culture minister Brian Mikkelsen was reported to have apologised to the Irish people for what the Vikings had done. He later denied having said sorry, telling a Danish newspaper, external: "What I mentioned in my speech was 'it did a lot of damages to the Irish people', but we don't apologise for what the Vikings did 1,000 years ago. That was the way you acted back then."

An apology 1,000 years on would have been absurd. But others question Mikkelsen's second point - that their behaviour was the norm.

The correction to "cuddly" Vikings had gone too far, says Prof Simon Keynes, an Anglo-Saxon historian at Cambridge University. "There's no question how nasty, unpleasant and brutish they were. They did all that the Vikings were reputed to have done."

They stole anything they could. Churches were repositories of treasure to loot. They took cattle, money and food. It's likely they carried off women, too, he says. "They'd burn down settlements and leave a trail of destruction." It was unprovoked aggression. And unlike most armies, they came by sea, their narrow-bottomed longships allowing them to travel up rivers and take settlements by surprise. It was maritime blitzkrieg at first.

Worse was the repeat nature of the raids. The Vikings, like burglars returning over and over again to the same houses, refused to leave places alone.

Images courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum, The National Museum of Denmark (gold neck ring) and National Museums Scotland (brooch)

Ivar the Boneless is said to have been particularly cruel. According to the sagas, he put Edmund, king of East Anglia, up against a tree and had his men shoot arrows at him until his head exploded. And Viking rival King Ella was put to death in York by having his ribs cut at the spine, his ribs broken so that they looked like wings and his lungs pulled out through the wounds in his back. It was known as the Blood Eagle. But the accuracy of these stories is disputed.

And others point out that the Anglo-Saxons were hardly upholders of a prototype Geneva Convention. In 2010 it was reported that 50 decapitated bodies had been found, external in Weymouth, thought to be executed Viking captives.

The Vikings also went west to Newfoundland, to northern France and Germany, and east into what is now Russia and Ukraine. Perhaps less known is the Viking influence in central Asia and the Middle East. "It's very difficult to find a single way of assessing them all because they did so many things," Keynes says.

The largest body of written sources on the Vikings in the 9th and 10th Century is in Arabic, points out James Montgomery, professor of Arabic at Cambridge University. The Vikings reached the Caspian Sea and came into contact with the Khazar empire. They may even have got as far as Baghdad if one mid-9th Century source is to be believed. Vikings known as the "Rus" are thought to have contributed to the formation of the princedom of Kiev, which turned into Russia, Montgomery says.

It has led some to paint the Vikings as global traders more than warriors. And even - with their Icelandic sagas - as inventors of the soap opera.

Revisionism is natural. Academics are always looking for a fresh angle. And people change their mind as social mores evolve.

"Stendhal said that the biography of Napoleon would have to be rewritten every six years," says historian Antony Beevor, author of The Second World War.

But revisionism and counter-revisionism happens more in some fields of history - World War One for example - than others. For Beevor it tends to occur "over periods and questions which have contemporary political resonances - civil wars, slavery and colonialism, labour, the treatment of women and so forth".

Townend says the Vikings were both invaders and migrants. They didn't just raid, pillage and leave. Over the 300-year Viking period, many stayed. Their attitude to the local populace was more complicated than just that of thuggish raiding parties. "They don't wipe them out. So how do these two groups live together?"

It becomes a story about not just conquest but immigration and assimilation. Many of the Vikings embraced Christianity. There was intermarriage. King Cnut, who became King of England and ruled for 25 years, replaced those at the top but allowed society to go on as before. At the same time they held on to Norse names and traditions. "My view is that there was a good deal of give and take," Townend says.

Haakon the Good converted to Christianity while in England. On his return to rule Norway, "he was given a hard time", Townend says. "His religious beliefs were rather different to the majority of his subjects."

What came after the Vikings was arguably worse, argues Tuckley. The Normans went about things in a more systematic way, he says. "They oppressed the local populace rather than integrating as the Vikings did."

No doubt the revisionism and counter argument will be fine-tuned. But the Viking story - replete with violence, colonialism and trade - has it all. With or without horns.

Discover more about the Vikings at BBC History.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external