The man from Martyrs Avenue who became a suicide bomber in Syria

- Published

Abdul Waheed Majeed moments before his attack in February

On 6 February, Abdul Waheed Majeed, from Crawley in West Sussex, drove a truck bomb into the gates of a prison in Syria. Does his death represent everything that the government fears about radicalisation on a foreign battlefield?

A little boy is standing on the sun-bleached pier at Brighton beach, next to his brother.

Complete with washed-out colours, it's no different to millions of other happy family snaps from the 1970s.

Fast forward four decades and the final images in the life of Abdul Waheed Majeed are quite different.

He is now standing in a sun-bleached road amid rubble and chaos. He's wearing a black bandana and a simple white gown. The man holding the camera appears to asked Majeed to say something. He appears reluctant, declaring that he is tongue-tied.

Chechen militiamen, apparently part of the al-Qaeda linked al-Nusra Front, pose as the British man raises a finger skywards. It is the classic pose of a would-be mujahideen "martyr".

Some time later, the road engineer who lived in Martyrs Avenue, Langley Green, West Sussex, is presumed dead. He has driven a massive truck-bomb into the gates of Aleppo prison in Syria. Fighters who filmed the attack shouted the customary cry "God is Great". The blast wave from the explosion has so much force it shakes the camera.

Waheed and Hafeez Majeed at Brighton as boys

"Abu Suleiman al-Britani" was the 10th British man to die on a Syrian battlefield - and the first to die in a vehicle-borne suicide bomb attack.

Inside Britain's security agencies, Majeed's death only added to a sense of growing crisis. Why did a 41-year-old father of three from a quiet town in West Sussex give up his life in a foreign war - and what does he represent?

Abdul Waheed Majeed was brought up in Crawley to Pakistani-born parents. His older brother, Hafeez, speaking on behalf of all the family, says that their life was no different to those of any other children in the area.

"We would go on our push-bikes together when we were young, we would go to the local park, feed the ducks, go to town, have a bite to eat at the fish-and-chip shop. Anything that a normal brother would like to do. As a family, we enjoyed doing things as one unit. We used to go to the Isle of Wight and have a great time."

Majeed eventually married and became a father-of-three. He got a steady and stable job as a highways engineer, often working in emergency crews repairing carriageways after motorway accidents.

But in July last year, he made a decision to do something big. The Syrian conflict was dominating the news. Muslim communities had been running massive fund-raising drives to send convoys to refugee camps on the border with Turkey. A Birmingham charity was co-ordinating a nationwide convoy and it needed drivers. Majeed told his family he wanted to volunteer.

"Waheed saw that there were people being oppressed, people with no food, people being torn apart from their families, people being put in prison," says Hafeez Majeed.

"He just thought that this was a great injustice. My brother wasn't the kind of person to send money in an envelope. He had to play his part and help."

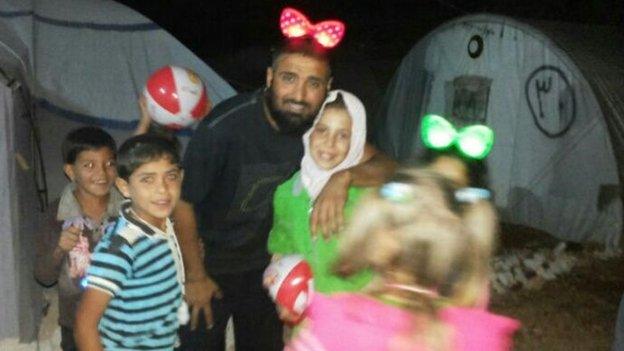

Friends in Syria: Waheed Majeed and Raheed Mahmood

Majeed persuaded one of his closest childhood friends, Raheed Mahmood, to join him on this journey. Mahmood has spoken for the first time about their time in Syria. "I had to ask myself what was keeping me from going," he says.

"I didn't want to go through my life continuously working, earning money, spending, eating, sleeping. Our faith calls for this kind of work - he knew me as a friend and could gauge my response."

The men left on the convoy and began sending regular messages and pictures home - some happy, some sad - many detailing the difficult conditions that the Syrian people were facing.

Over the months to come, Majeed's family say he sent reports showing how he was working on camp construction, improving the lay-out and sanitation of the tent cities. As the months wore on, the war took its emotional toll. Mahmood says he and Majeed would often listen to ordinary families tell of how their lives had been destroyed.

"You could not help but see the glaze in his eye, you can see almost a tear because some of these stories are shocking. Whether he acknowledged it or not, I could see the emotions running high."

And by the end of the year, the families were urging the men to return.

Hafeez Majeed says: "There was that point when my parents did say, 'We feel you have done your part in Syria.' His [Majeed's] response was always that there was so much more that he could offer these people... 'my journey has not finished yet'."

"Eventually it has its toll on you," says Mahmood. "You miss your wife and your children, the comforts of that life. A man can only bear so much. You could see that I was ready to go and I could see that he wanted to continue. I found it very emotional."

In the camps: Pictures sent home by the men from the Syrian refugee camp

Mahmood came back to the UK in January on board a returning British convoy. He remained in contact with Majeed via the internet until he received a final and, with hindsight, odd message.

"He told me that he would be out of contact for a while, which was not unusual, but he did tell me to forgive him for any errors and to ask the other brothers to think good of him. I felt that he was quite emotional. I was a bit unsure. It was from the heart. [I thought] maybe he was coming back soon."

But he didn't come back.

About a week had passed with no contact from Majeed. Neither friends nor family had heard from him.

On Thursday 6 February Majeed apparently got into the cab of an armoured truck, filled with explosives. There were tiny slots in the armour allowing him to see the road ahead and to the side. Amid heavy gunfire, he drove straight at the prison gates.

The local fighters he had joined believe that the explosion allowed hundreds of prisoners to escape - although there is no independent way of verifying that report.

It was days before Majeed's family and friends realised that he had been involved. Mahmood was the first to make the link after he was able to contact aid workers in Majeed's camp who confirmed that he had apparently disappeared to join a militia.

"One side of me said that this must be verified," says Mahmood. "And then you come to realisation that this has definitely taken place... How do you respond?

"I wasn't really able to contain my emotions, I was quite tearful. I don't think anyone could be prepared to handle that kind of information. I started to think, how do I relay this to my family? What do I say, how do I get these words out? How do I tell his children?"

And then the video emerged - making words unnecessary.

Footage shot moments after the explosion at Aleppo prison

"When I saw that video, I did not recognise my brother," says Hafeez Majeed. "He was around people that he seemed to hardly know. He looked totally different, as if he should not have been there.

"My heart sank, my mum and dad's hearts sank, we were extremely grief-stricken when we saw that moment, extremely shocked, deeply, deeply worried. You just don't know what to think when the last contact you had with him, everything seemed normal.

"For things to jump in the course of a week to him standing by a truck and that truck being driven into a military prison compound, it was extremely difficult for us, emotionally, as a family to comprehend."

The family contacted the police and government for help. Officials took DNA samples and dental records. Police also used counter-terrorism powers to seize computers and phones to look into Majeed's past and the communications he had sent home.

The police still have those computers - but the mood among security chiefs appears to be that his death could not have been predicted.

But given this is a foreign war, why should British security chiefs be so concerned?

Ahmed Maher looks at the facts, figures and reasons for the conflict in Syria.

Crawley is no stranger to tales of global jihad because some men from the town have been part of the broad network of radical Islamist thinking that advocates the belief that Muslims in the West have a duty to fight for Islamic causes abroad.

Back in 2001, a local man died as the Americans bombed Taliban and al-Qaeda positions in Afghanistan.

The banned group al-Muhajiroun operated a prayer circle in the town until around 2004. One of the group's Crawley followers went further and received bomb-making training from al-Qaeda associates in Pakistan. He and two others from the town were convicted and jailed for life for leading a major bomb conspiracy, known as Operation Crevice. Majeed knew some of these men because he grew up alongside them and, for a time, attended the same al-Muhajiroun circles.

During the Crevice investigation, an al-Qaeda supergrass described Majeed as an associate of the British men he knew in the UK and, briefly, in Pakistan.

Those claims have not been tested in court because Majeed was never arrested or charged in relation to Crevice or any other British terrorism investigation.

"My brother was not fully involved with Al-Muhajiroun," says Hafeez Majeed. "At that early stage of his life he was dipping his toes into different types of groups. The views that they espoused did not marry with what his beliefs were."

Mahmood's brother was among the three Crawley men jailed for life in Operation Crevice. But Mahmood says that neither he nor Majeed harboured jihadist views that were eventually played out in Syria. He insists that they rejected that thinking long ago.

"There was a period during the early development [of our faith] when we did want to understand the various perspectives, the various views that people had formed," he says.

"We disagreed with al-Muhajiroun - the message and the styles and the means of how they put that out. So, just respectfully, as we did with many other movements, we moved on."

Social media sites including Twitter and YouTube are awash with reports from the jihadist frontlines in Syria.

Security chiefs in Whitehall believe that the number of men from Britain thought to have fought in the country has now reached the upper end of the low hundreds. Half of these men may now be back in the country - and MI5 fears "blowback".

It worries that history may be about to repeat itself - men could be returning battle-hardened and radicalised and, in some cases, prepared to carry out attacks on the UK's streets in a protest against foreign policy.

Police have stepped up their own investigations and operations. So far this year, more than 30 people have been arrested.

Speaking to Newsnight, security minister James Brokenshire warns there is genuine cause for concern. "Syria has become the jihadi destination of choice," he says. "I understand the desire for people to want to help, to give that humanitarian assistance but travelling out there puts them at risk how they may be radicalised and brutalised by the experiences they see."

But the idea of a direct line - a thread linking al-Qaeda, the Syrian jihad and a threat to British national security, isn't universally accepted.

Back in Crawley, young people at the town's main mosque talk about Majeed's death. "Previously, suicide bombings have been targeting innocent civilians, like 7/7," says one prayer-goer, Zeeshan Hussain. "But as far as I'm aware, no innocents were targeted [by Majeed]. Although you could question what he was doing, I wouldn't say he was terrorising anyone. The people who say it was an act of terrorism, who are they saying he's terrorising?"

Many British Muslims share Hussain's view that Syria's jihad has blurred lines. Al-Qaeda linked groups are involved - but many people believe that the conflict is closer in character to the civil war in Bosnia. Some compare it to the Spanish Civil War in which international brigades of young men fought against General Franco.

Mohammad Huzaifa Bora, the imam at Crawley mosque, says nobody wants to break the law - and his community is abiding by advice not to organise any more convoys. But people are confused about where the British government stands. "It's very conflicting, very confusing - the message. And it came too late," he says. "All those convoys, and all those youths, they are there."

A British aid convoy at the Turkish-Syrian border

Brokenshire says the government's message is clear. "People should not travel to Syria because of the risk that it poses to them and how actually it makes matters worse. It does not assist in terms of the Syrian people who have said very clearly they don't want foreign fighters. They want humanitarian aid."

Asim Qureshi, of campaign group Cage, external, says there has been a failure to properly analyse why Majeed carried out his attack. He says the government must differentiate between the different armed groups in the conflict and their military intentions and methods. He says it was impossible to say for certain whether the Crawley man intended to die - so it is impossible to attach a clear motive.

"If you look at what is going on in Syria, then you will see that it falls in line with any other civil conflict anywhere in the world," says Mr Qureshi. "Some people will feel very, very strongly about fighting against injustice because they want to fight those who are being oppressed. But if British citizens were involved in war crimes, then they should be held accountable."

One of Cage's founders, Moazzam Begg has been charged with terrorism-related offences in Syria. He denies the charges.

So why did Majeed do it? Was there some kind of unbroken ideological thread from his radical past to his death in Syria? Is he a textbook study of the "conveyor belt" of extremism?

Mahmood says that he agrees that there needs to be a debate about the threat of blowback - but he says that Majeed "doesn't tick any of the boxes".

"The events of Crevice, al-Muhajiroun and Syria - there is almost a 15-year gap," he says. "The events that took place in Syria were based solely on what Waheed experienced in Syria."

The family speculate Majeed was motivated to fight by a major report in January that detailed evidence that the Assad regime was torturing, starving and executing prisoners. They now believe he gave his life trying to free some of those detainees.

But was he a violent jihadist, just waiting for his chance - either at home or abroad?

"My brother was not a terrorist. My brother was a hero," says Hafeez Majeed.

"If I could put it like this: if my brother had been a British soldier and there were British people in that prison, I know he would have been awarded the posthumous Victoria Cross.

"My brother paid the full price with his life for what he did. He was not a threat to the British public and never has been a threat to the British public."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

- Published10 July 2015

- Published24 December 2013

- Published20 November 2013