A Point of View: The case for not leaving education to the teachers

- Published

We should not expect education to be simply left to teachers, or the state, argues the philosopher Roger Scruton.

Since the Middle Ages, education has been regarded in this country as a public duty. Originally the duty did not fall on the state. It was a general charitable duty, to which wealthy people responded by establishing schools and colleges, setting up the trusts that would fund them, and providing scholarships for poor pupils. A statute of Elizabeth I defined education as a charitable purpose, entitled to certain legal and fiscal privileges. Over the following centuries new schools proliferated, often established by the Anglican and non-conformist churches. In 1833 the government introduced an annual grant to two charities that provided both church schools and non-denominational schools for poor children. As a result of those and similar moves education rapidly expanded during the first half of the 19th Century, to the point where it was unusual for a child not to acquire sufficient numeracy and literacy to survive in the competitive environment of the industrial cities.

Eventually Parliament passed laws compelling all children aged five to 13 to attend a school, beginning with the Education Act of 1870, which obliged the state to step in and pay the fees for families who could not afford them. Since that time the state has increasingly taken the initiative, establishing primary and secondary schools, raising the school-leaving age and, in due course, creating new universities and colleges designed to make a full education available to everyone. But while the state extended our educational system, it did not create it. As the system expanded in the 18th and 19th Centuries, it was private individuals, charitable trusts and religious foundations that took the most important steps. The state inherited well-funded, long established and dedicated institutions and a tried and tested curriculum that large numbers of people knew how to teach. Of course, there were barriers of wealth and class that could not be easily crossed, as the Victorian novelists remind us. But there was also a culture of respect for education, and an eagerness to teach and to learn.

I was a child from a poor background who was lucky enough to attend the local grammar school. Our school had been established by royal charter in 1562, and had inherited the standards and traditions associated with the public schools. Like most of the grammar schools it was funded by the state, and I received the best possible education for free, leading to a scholarship to Cambridge. But to enter grammar school I had to pass an examination, which I took at the age of 11, and those of my classmates in primary school who failed that examination had to go to the local secondary modern, where inevitably standards were not so high and the long-term prospects less favourable. Not surprisingly it seemed to many people unjust and politically unacceptable that the prospects of poor children should be decided at the age of 11. Hence there was a long-standing and eventually successful campaign to abolish that examination and to amalgamate the grammar schools and the secondary moderns into comprehensives.

The intentions behind that reform were the best. And when Anthony Crosland, education minister under a Labour government, called on local authorities to submit plans to go comprehensive, the response was largely positive. The policy was pursued under both Labour and Conservative governments and as a result most of the grammar schools were either absorbed into comprehensives or deprived of state funding. Thereafter only people with money could obtain the kind of education that I once obtained for free. This was hardly an advance from the point of view of social mobility, and certainly not a way of rectifying the inequalities that had inspired the reforms in the first place.

Anthony Crosland was education minister under Harold Wilson

The response of many egalitarians to the widening gap between state and private education is to call for the removal of all privileges from the private schools - then all children really would be equal, and nobody could obtain a better education than average merely by being wealthier than the rest of us. But, besides being a vast trespass on the freedom of citizens, such a reform would have the same effect as the abolition of grammar schools. Rich people would bypass the schools, establishing home schooling networks as they do in America. Or they would ensure that their children are provided in the evenings with the resources of which they are deprived during the day.

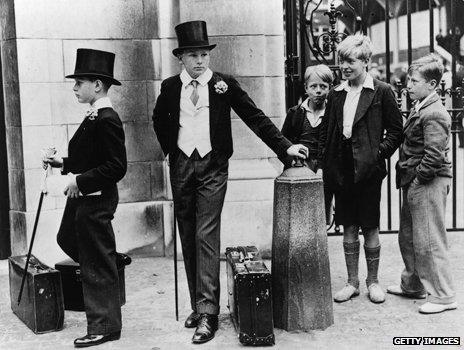

Harrow schoolboys observed by locals outside Lord's, 1937

The history of education in this country since 1870 shows us that the state is better at placing obstacles in the way of teaching than encouraging people to take it up. Teaching qualifications, once regarded as a badge of merit, became obligatory during the post-war period, to be imposed by law as the sole route into the state system. Knowledge was no longer a sufficient qualification. And soon it wasn't a necessary qualification either. After a hundred years of domination by the state our education system, which was once one of the best in the world, fails to make the top 20 on the scale issued by the Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa). The answer, it seems to me, is not to go further down the path of state control - closing down this school and meddling in that one - but to encourage people to do what they did in the early 19th Century, which was to take charge of schooling for themselves. Education, we must remind ourselves, is not about social engineering, however laudable that goal might be. It is about passing knowledge from those who have it to those who need it.

BBC's Tough Young Teachers showed graduates in the Teach First programme

Our country is full of people who know things, and of children who want to learn things. A successful education system is one that brings the two together, so that knowledge can pass between them. In every village there are people with knowledge that would be useful to the young - retired accountants and lawyers, musicians and singers, those who speak a foreign language, writers, plumbers, farmers, engineers and amateur historians. And many of those would welcome the opportunity to teach what they know. Somehow we have failed to harness this capital, letting it go to waste while our children drift in search of it. Gradually our governments have begun to wake up to this fact. We are seeing a revival in government circles of the old idea of education as a charitable gift from one generation to the next, rather than a form of state-controlled social engineering.

One encouraging development has been the establishment under a Labour government of the Teach First programme, which allows people with knowledge to learn the art of teaching as one learns to ride a bicycle - namely by doing it. This removes the obstacle created by the old state qualifications and helps to resurrect the idea of teaching as a vocation. The establishment of academies, which enables some specialist schools once again to set standards for entrance, has created for poor children some of the opportunities enjoyed by the rich. And the present government is allowing citizens to start schools within the state system. A free school can settle its own curriculum and contracts of employment. It can therefore open the way for those with unused knowledge to impart it in the classroom, and for volunteers to help with extra-curricular activity. Anyone can apply to set up such a school, provided they have sufficient educational and financial expertise within their core team, and the willingness to make a substantial time commitment. Parents, local businesses, and volunteers can all join in the enterprise, whose goal is to rescue children from disadvantage and once again to open the channels through which the social and intellectual capital of one generation can flow into the brains and bodies of the next.

In the past the British people have solved their problems in precisely that way - not by handing them over to the government and then forgetting about them, but by sorting things out for themselves. The philanthropic middle classes, who created our education system and made it one of the best in the world, have been for too long excluded from it. But they possess the knowledge that we need, as well as the time and the energy to hand it on to our children. Bring them back into the system, allow them to do whatever is needed to impart their assets to the young, encourage them to raise funds, to recruit volunteers, to expand the curriculum, and all children will benefit. In the conflicts over education all sides have claimed to be extending opportunities to the poor. But the politicians are at last beginning to recognise that opportunities are not increased by closing things down, but by opening things up.

A Point of View is broadcast on Friday on Radio 4 at 20:50 GMT and repeated on Sunday at 08:50 GMT. Catch up on BBC iPlayer

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external