Is Afghanistan really impossible to conquer?

- Published

The Soviets began their withdrawal in 1988

It's 25 years since the Soviet Union pulled its troops out of Afghanistan. The US is due to remove most of its forces at the end of the year. So what have these and other Afghan campaigns taught us?

Last Ramadan I drove through the badlands outside Kandahar to see the house where President Karzai grew up. I was the guest of the president's brother, Mahmoud Karzai.

"It has changed beyond all recognition," he said as we drove into the village of Karz. "This mosque I remember. I used to play with Hamid over there. But where is our house?"

The driver pulled up. "This is it?" asked Mahmoud. "It cannot be."

We got out in a flat field of dried mud, surrounded by mud-brick houses. Mahmoud's bodyguards fanned out while Mahmoud climbed on a small eminence. "The driver's right," he said. "This is our home." He gestured at the empty space.

"What happened?" I asked.

"The Russians," he replied.

"Why?"

"Any clan prominent in the mujahideen had their property demolished. These houses were where my cousins lived. The night the Soviet governor demolished our house, they were all lined up. Then they were shot. Every last one of them."

It is now the 25th anniversary of the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, and it is perhaps a good moment to compare the Soviet and American interventions.

On the surface, the two invasions are quite different - the Soviets came to extend the Soviet Empire while the West, we are told, intervened after 9/11 to root out the terrorism and bring democracy. Yet there are many uncomfortable similarities.

Both the Russians and the Americans thought they could walk in, set up a friendly government and be out within a year. Both nations got bogged down in a long and costly war of attrition that in the end both chose to walk away from.

The Soviet war was more bloody - it left 1.5 million dead compared to an estimated 100,000 casualties this time around, but this current war has been far more expensive. The Soviets spent only $2bn (£1.2bn) a year in Afghanistan while the US has already spent more than $700bn (£418bn).

Moreover this time arguably less has been gained. Twenty-five years ago the Soviets withdrew leaving a relatively stable pro-Soviet regime in place - Najibullah's government collapsed only when the Soviets cut off supplies of weapons a full four years later.

But 13 years after the West went in to Afghanistan to destroy al-Qaeda and oust the Taliban, America and its Allies find themselves about to withdraw with neither objective wholly achieved.

What remains of al-Qaeda has moved to the Pakistani borderlands, and elsewhere, while the Taliban have a major influence over maybe 70% of southern Afghanistan. That share can only increase later this year when the British and the Americans withdraw most of their troops.

There is another precedent to this war. For the last five years, I have been writing a history of the First Anglo-Afghan War which took place from 1839-1842.

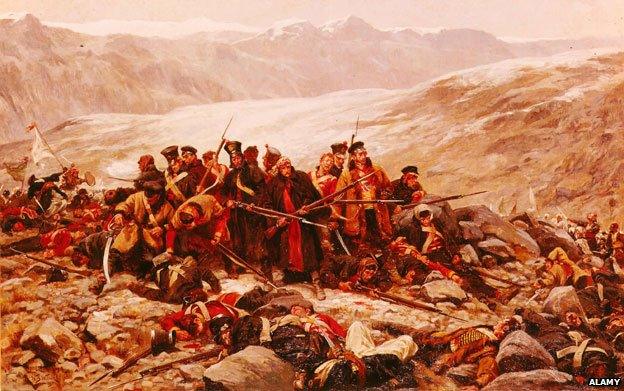

The book tells the tale of arguably the greatest military humiliation ever suffered by the West in the East. The entire army of what was then the most powerful nation in the world was utterly destroyed by poorly-equipped tribesmen.

On the retreat from Kabul, of the 18,500 who left the British cantonment on 6 January 1842, only one British citizen, the assistant surgeon Dr Brydon, made it through to Jalalabad six days later.

The British withdrew in 1842 after a disastrous campaign

The parallels between the current war and that of the 1840s are striking. The same cities are being garrisoned by foreign troops speaking the same languages, and they are being attacked from the same hills and passes.

Not only was our then puppet, Shah Shuja, from the same Popalzai sub-tribe as President Karzai, but his principal opponents were the Ghilzai tribe, who today make up the Taliban's foot soldiers.

It is clearly not true, as is sometimes said, that its impossible to conquer Afghanistan -many Empires have done so, from the ancient Persians, through Alexander the Great to the Mongols, the Mughals and the Qajars.

But the economics means that it is impossible to get Afghanistan to pay for its own occupation - it is, as the the then Emir said as he surrendered to the British in 1839, "a land of only stones and men".

Any occupying army here will haemorrage money and blood to little gain, and in the end most throw in the towel, as the British did in 1842, as the Russians did in 1988 and as Nato will do later this year.

In October 1963, when Harold Macmillan was handing over the prime ministership to Alec Douglas-Home, he is supposed to have passed on some advice.

"My dear boy, as long as you do not invade Afghanistan you will be absolutely fine," he said. Sadly, no one gave the same advice to Tony Blair.

It just seems to prove Hegel's old adage that the only thing you learn from history is that sadly no one ever learns anything from history.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external