Bob Crow: The union leader everyone had heard of

- Published

Bob Crow, who has died at the age of 52, was an intensely divisive figure. But he was easily the best-known trade unionist in the UK.

One of the barbs most commonly levelled at Bob Crow as leader of the RMT union was that he was a "dinosaur". A relic of a bygone age when unions had a place in national life.

In a memorable interview last month, the BBC's Jeremy Paxman raised the point. "You're a dinosaur." And Crow's response?

"Well, at the end of the day, they was around for a long while."

Crow went on to set out the aims of a trade unionist: "Job security, being safe, best possible pay, best possible conditions, decent pensions, and a world that lives in peace."

That simplicity of approach has been reflected in the reaction to his death. To his admirers he was a working-class hero and fighter who stood up for his members and won. To his enemies he was a bully who inflated his workers' wages by bringing misery upon commuters.

Crow at the Durham Miners Gala calling for the creation of "a new party of labour"

One of Crow's more remarkable achievements was becoming one of the UK's best-known characters at a time when the rest of the nation's trade union movement had faded into comparative obscurity compared with its 1970s heyday.

Len McCluskey and Dave Prentis lead the two biggest unions in the United Kingdom with 1.5m and 1.3m members respectively. But neither is remotely as well-known as was Crow. "He was Britain's best-known trade union leader by a country mile," says Kevin Maguire, associate editor of the Daily Mirror. "He was the only one who would actually get stopped in the street by people."

It wasn't just his willingness to lead his members into strike action that earned him this profile. It was also the extravagant Bob Crow persona.

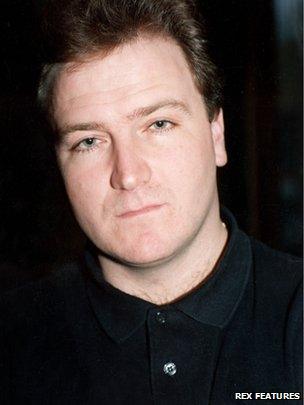

Bob Crow in 1992, a year after he became assistant general secretary of the RMT

He was the Millwall supporter (club chant: "No-one likes us, we don't care"), the council house-dweller who earned more than the prime minister, the firebrand left-winger with a bust of Lenin on his desk and a Staffordshire bull terrier named Castro.

There was his physical appearance, too. The flat caps and duffel coats. An almost cartoonish, bull-necked rendition of an East End hardman, he looked like a character in an early Guy Ritchie film, but maintained in interviews, external he hadn't thrown a punch since he was at school.

He was also a bluntly articulate advocate for transport workers whose unmistakable Essex vowels could regularly be heard on the Today programme or the rolling news channels cutting through the detail of the latest bargaining round or terms and conditions dispute.

There was also the fact that, on his own terms, he was hugely successful. The Rail, Maritime and Transport Union's membership soared from 50,000 to 80,000 during the first seven years of his leadership.

And this in turn was, of course, because of the wage rises - frequently above inflation - that he delivered for them, not to mention the generous terms and conditions they enjoyed. According to Transport for London, Tube drivers earn £50,000 a year as well as the right to free travel on the TfL network - for them and one other nominated person.

Such was the pervasiveness of his public image that many would assume that his union represents every single Tube worker. It doesn't - Aslef (the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen) represents 70% of the drivers.

The RMT represented everyone from North Sea oil rig workers to provincial train drivers, but it was Crow's marshalling of London transport workers that earned his role in the spotlight. There is no other British city that can be brought to a standstill in quite the same way London can.

The Tube strikes could generate massive pulsating crowds outside stations, shoving matches at bus stops and 10-mile walks to work. This has always been given a prominence in the media that other disputes have not enjoyed.

Bob Crow interviewed by Jeremy Paxman in February 2014

In the eyes of his opponents, Crow's achievements were gouged out by exploiting his position in order to inflict misery on travellers. But to his members it was a testament to his tactical acumen, negotiating skills and mastery of industrial relations.

What also made him stand out in an era of slick, well-groomed, professionalised politics was a habit of saying the unsayable.

Whether it was his politics - he steadfastly described himself as a "communist/socialist" - or his willingness to swear in interviews, he was to many a bracing counterblast to the bland homogeneity of modern politics.

In some newspapers he was derided as a "champagne socialist", a "blackmailing union bully" and guilty of "sickening hypocrisy". His holidays were seized upon and mocked - "lobster-red baron" was one jibe. But he gave as good as he got.

When criticised for taking a holiday in Rio ahead of strike action by RMT members, he retorted: "What do you want me to do, sit under a tree and read books of Karl Marx every day?"

"Trade unions are undoubtedly weaker than they were 20 or 30 years ago and politicians have been put through the dishwasher to never put a word out of place," says Maguire. By contrast, he adds, "big, burly, shaven-headed Bob told it like it was".

In fact, industry insiders reported that he was more prepared in private to strike a bargain than his public images suggested.

"Behind the scenes he was a very canny negotiator," says rail expert Christian Wolmar. "He would do this thing of taking a public stance, making a lot of noise, using the media to good effect to battle away for his cause, while behind the scenes he would be negotiating quite carefully, really tried hard, to avoid the strikes which publicly he was calling for."

All this made him a figure who inspired admiration and even affection from his political opponents.

His long-time foe Boris Johnson, with whom he frequently clashed, hailed him on Twitter as "a man of character who fought tirelessly for his members". Ukip leader Nigel Farage tweeted: "Sad at the death of Bob Crow. I liked him and he also realised working-class people were having their chances damaged by the EU."

In fact, it was often with Labour figures that Crow - an erstwhile member of the Communist party - most frequently clashed. The RMT was kicked out of Labour after some branches voted to support left-wing rivals. Tony Blair, he once said, "squandered a massive landslide from an electorate hungry for change, poured billions of public pounds into private pockets and accelerated the growing gap between rich and poor".

His right-wing opponents made much of his large salary. To his members, however, this working-class-boy-made-good persona only burnished the notion that he was fighting to win the same for them, too.

"He didn't apologise for his salary, he didn't apologise for his lifestyle. What mattered was that the union grew under him and that he delivered for his members," says Roger Seifert, professor of industrial relations at the University of Wolverhampton. "He was totally proud and upfront about his own working-class origins and he was unabashed and unashamed about representing the interests of his members."

This quote by Bob Crow defending himself against these charges perhaps describes his philosophy better than any other.

"This trade union fights for the right of our members to enjoy the finer things in life," he said. "Why should it just be the bankers, politicians and the idle rich who get all the best things? As a militant trade union we demand a standard of living for our members that enables them to share in the fine wines and fine times that the likes of David Cameron and his Old Etonian mates take for granted."

Whether regarded as a bullying dinosaur or a defender of the workers, he leaves behind no-one else quite like him.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external