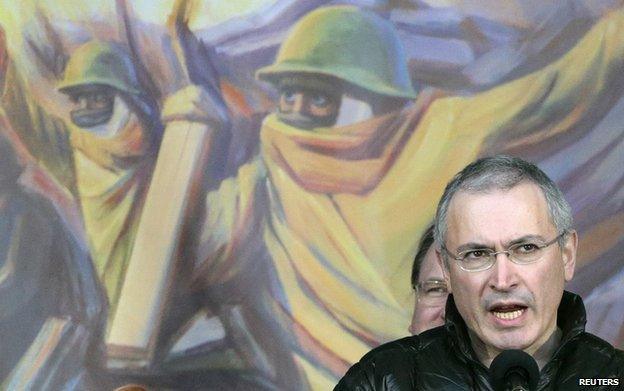

Ukraine crisis: Russians opposed to Putin

- Published

In an emotional speech in Kiev on Sunday, former Russian oil tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky - recently released from 10 years in jail - told the Maidan "there is another Russia", one opposed to military action in Ukraine. Russian writer and broadcaster Andrei Ostalski agrees but says it's a small and embattled community.

On 2 March, one day after the Upper Chamber of the Russian parliament passed a motion allowing President Putin to use Russia's armed forces anywhere on Ukrainian territory, a Muscovite decided to stage a one-man protest. He knew it was a rather risky affair as the streets were full of "patriotically" minded people rejoicing and celebrating the prospect of a quick victorious war against their neighbour.

Nevertheless, Alexei Sokirko found a place on the pavement on Nikolskaya Street and unfolded his "Stop the war" banner.

Russian law allows one-man pickets to be staged without prior permission or advance notification so the police didn't do anything at first. In fact, they didn't need to as Alexei immediately started getting harassed by angry passers-by. To begin with they called him "fascist" and "scum". Then a woman spat at him. A few men started threatening him, and finally one of them snatched the banner from his hands and tore it up.

A scuffle followed - that was when the police intervened to arrest Alexei for violating public order. It was probably just as well, as he could have been seriously beaten. A woman then offered to fabricate a more serious charge against him. "I can testify that he was beating up a child," she suggested, enthusiastically. The policemen decided not to take her up on it.

A lone peace protester in Moscow

The episode described on Alexei Sokirko's Facebook page, external is poignantly symbolic. Russians opposed to the invasion of Crimea are a lonely minority, seemingly powerless to influence the mob that surrounds them.

According to one poll, external, about 70% of the population approves of Putin's policy towards Ukraine. Especially popular is the prospect of Crimea becoming part of Mother Russia - and all the indications are a majority wouldn't mind Russia sending tanks straight to Kiev. Dmitry Peskov, the president's press-secretary, claims Putin's ratings are at an all-time high.

It's become something of a mantra in Moscow to say that Russians are so pleased with the way their macho leader is "standing up to the West" and "defending compatriots abroad" that they are prepared "to forgive him everything" - from widespread poverty to endemic corruption and police brutality.

The popular Russian novelist and scriptwriter Tatiana Sotnikova (pen name Anna Byerseneva) agrees that most of her compatriots support the Kremlin's actions, for now at least - she thinks it could change if Russia's isolation causes living standards to fall. She attributes their bellicosity mostly to the incessant propaganda of the national TV channels. "A total xenophobic brainwashing has been going on relentlessly for the last 14 years," as she puts it.

She is one of a number of Russian writers who signed a letter expressing solidarity with their Ukrainian colleagues and protesting against Moscow's belligerent behaviour. The writers, all members of PEN International, are not entirely alone. One of the two Russian cinematographic unions joined in the condemnation. (It is a sign of the times that Moscow has another, more "patriotic" Union of Cinema Workers that would never dream of challenging the Kremlin line).

But the Russian Union of Writers announced its total support for any actions the president might undertake on Ukrainian territory, and echoed Kremlin rhetoric by calling the Maidan leaders "a bunch of fascists".

There have been others, too, who have carried out their own version of Sokirko's protest.

Andrei Zubov, a highly respected professor at the prestigious Moscow State Institute of International Relations, wrote an article in Vedomosti newspaper comparing a Russian annexation of Crimea to the German Anschluss of Austria in 1938. He was immediately told to resign or face the sack but the threat was retracted after colleagues rushed to his support.

One of the least expected objections came from a leader of the pro-Kremlin Spravedlivaya Rossiya party, Akexander Chuyev, writing on a liberal website.

Regardless of a person's political views and affiliations, supporting a war was immoral, he said, adding that he knew communists and nationalists who shared his view. "As a Russian and an Orthodox Christian I cannot support a decision which not only contradicts Russia's international obligations but can lead to a fratricidal war," he announced in a separate interview.

The editor of the influential Nezavisimaya Gazeta, Konstantin Remchukov, has meanwhile spoken out against the idea of holding an "illegal" referendum in Crimea. In a radio interview he also criticised, in no uncertain terms, the Russian establishment's apparent readiness to quarrel with the West. As he uttered those words listeners started calling in to brand him a "traitor" and worse.

Novelist Boris Akunin predicts unrest in Russia

One of Russia's most popular thriller writers, Boris Akunin, has also called on his compatriots to think again. "I want to ask the majority celebrating the annexation of Crimea: Do you have any idea about the price you will have to pay for this trophy?" he wrote on his Facebook page, predicting political and economic isolation.

"Thanks to his Crimea adventure, Mr Putin has guaranteed himself a life-term in office but I doubt that this term is going to be particularly long," he wrote. "In the absence of a legal mechanism for changing a bankrupt regime the mechanism of revolution switches on. And a revolution in a multi-ethnic country equipped with nuclear weapons is a truly frightening thing."

Akunin may well be proved right in the longer term, but at the moment there is little evidence of an anti-war movement spreading outside the thin layer of the Russian intelligentsia.

To some it is even invisible. Khodorkovsky's comment about "another Russia" was picked on by Matvey Ganapolsky, one of Russia's most popular political commentators (and a Ukrainian by birth). "He failed to explain why this 'other Russia' is invisible and silent," Ganapolsky wrote in his blog.

Last week small improvised protests were held in some Russian cities. In St Petersburg, 75-year-old Igor Andreyev was fined 10,000 roubles, external for holding a banner saying "Peace to the World".

In Moscow, hundreds of protesters were detained by police, many of them also later fined, though city authorities have now given permission for a bigger March of Peace, planned for Saturday.

So there is indeed another, thinking Russia, even if her inhabitants are not all that numerous. The worry is that if predictions of a further tightening of the screws by the Kremlin prove true, this important little community could be pushed into extinction.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external