Meet Jonathan, St Helena's 182-year-old giant tortoise

- Published

Our world is full of weird and wonderful creatures, many of which amaze scientists and non-scientists, alike. But is it true that a living tortoise could have started its life in the first half of the 19th Century?

Plantation House in St Helena sits proud amid gumwood trees alive with chirps and whistles.

It is the official residence of Mark Capes, Governor of the British Overseas Territories in the South Atlantic. I have not come to see the governor, nor the large brown hillocks which dot the pristine lawns.

It's only when my guide Joe Hollis, the sole vet on the island, bangs on a large metal bowl, that all becomes clear. The hillocks rise and trot surprisingly swiftly towards us.

Meet Jonathan, Myrtle and Fredrika, three of five giant tortoises who live on St Helena. Their shy friends David and Emma are hiding in the rough.

"He is virtually blind from cataracts, has no sense of smell - but his hearing is good," Joe tells me. At 182, Jonathan may be the oldest living land creature.

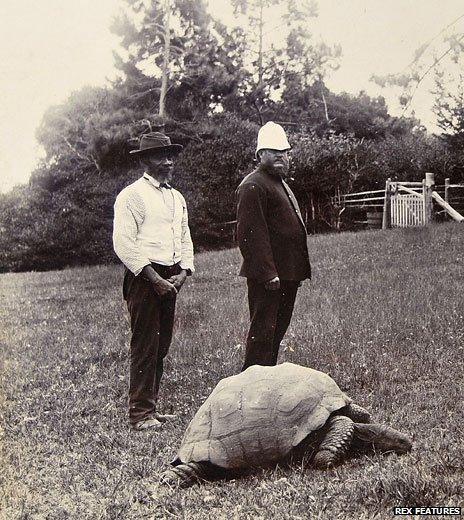

Jonathan, a Boer War prisoner, and a guard, around 1900

Jonathan is a rare Seychelles Giant. His lawn-fellows hail from the Aldabra Atoll in the Indian Ocean. Aldabra Giants number about 100,000, but only one small breeding population of Seychelles tortoises exists.

St Helena was born as a violent volcano, and along with Ascension and Tristan du Cunha in the South Atlantic, is famed for its isolation and close-knit society. Jamestown, its capital, became a centre of commerce for the East India Company in the 17th Century.

Many victims of the slave trade - sick and dying - would spend their final hours on the shores of St Helena. And then there was Napoleon, in exile.

Its inhabitants, known as Saints, share this complex past, and ethnic traits of Africans, Americans, Europeans and Chinese.

Nobody knows why Jonathan ended up in St Helena.

During the 17th Century ships could contain hundreds of easily-stacked tortoises, like a fast-food takeaway. In the Galapagos islands alone around 200,000 tortoises are thought to have been killed and eaten at this time.

How did Jonathan avoid this fate?

Maybe he became a curio for Hudson Janisch, governor in the 1880s.

Thirty-three governors have come and gone since then, and nobody wants Jonathan to die on their watch. Mr Capes is certainly keen "that he should be treated with the respect, attention and care he surely deserves".

A photograph taken in 1882 shows Jonathan at his full size, and it can take 50 years to reach that physical maturity.

The years since haven't always been kind. Tourists would often do whatever it took to get "that" photo.

Now, a viewing corridor runs along the bottom of the lawn to keep overzealous sightseers at bay. It was a huge privilege for me to get so up close and personal.

Jonathan loves having his neck stroked. His head extends out from his shell to a surprising length.

He snaps for his food - bananas, cabbage and carrots - with some ferocity. Joe almost lost the end of his thumb and has resorted to wearing thick gloves.

"He doesn't mean to nip me," he says, "he just finds it difficult to locate his food."

Tortoises scrape at the grass with their horny beaks, made from keratin, like nails.

Blindness made it hard for Jonathan to find the right vegetation, and due to malnutrition Jonathan's beak became blunt and soft, adding to his problems finding food.

Now there's a new feeding regime, in place where Joe delivers a bucket of fresh fruit and vegetables every Sunday morning.

With this extra nutritional boost Jonathan's skin now looks plump and feels supple.

His beak has become a deadly weapon for anyone attempting to shove a carrot anywhere near his mouth. And he can belch.

Tortoises may be slow but they are noisy, especially when they mate: "A noise like a loud harsh escape of steam from a giant battered old kettle, often rounded off with a deep oboe-like grunt." Joe reassures me it's another indicator of good health.

Unfortunately, Jonathan's trysts have not produced young - thus far.

Though giant tortoises like Jonathan can live up to 250 years, the community has already drafted a detailed plan for when he finally pops his shell - dubbed "Operation Go Slow".

It will ensure all runs smoothly when the inevitable happens, in fact his obituary has already been written.

It has also been decided that stuffing Jonathan would be a rather morbid and outdated thing to do.

Instead his shell will be preserved and will go on display in St Helena.

The Saints would like to raise funds for a life-size bronze statue of him.

When he goes, Jonathan will be mourned by friends and admirers on St Helena and around the world.

But to me, he is also a symbol of a remote society, soldiering on in genuine isolation.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent:

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external